Yi Wang (Cizzoe)

Where do you live: London

Your education: MA Contemporary Art Practice, Royal College of Art, UK; MA Ethnographic and Documentary Film (Practice), University College London (UCL), UK; BA Film Practices, Newcastle University, UK

Your discipline: Interdisciplinary practice spanning installation, performance, documentary film, video, and participatory art.

Website | Instagram

Yi Wang (Cizzoe) | Yi Yi | 2022

How did your background in social anthropology shape the way you approach art and audience participation?

Looking back, my training in ethnographic and documentary filmmaking was deeply grounded in social anthropology. From that point on, everything I made began with people, to understand different groups, their ways of living, and their unique experiences within certain communities or within society at large. That perspective became the backbone of my early documentary practice, and later opened up a new way for me to think about making art.

I’ve always seen my artwork as a kind of ongoing field research. Each project is an attempt to understand how we, as human beings, exist and relate to the world around us. The anthropological lens guided me to stay curious and open, to approach every person and social issue with sensitivity rather than judgment. The ethnographic fieldwork methods I embodied early on still shape how I start any project today, I begin by immersing myself, by physically experiencing and observing before anything else. Those firsthand encounters then become material that I process through my own perception, translating them into different artistic forms and media for the audience to experience, sometimes through visual such as documentary film, sometime through sensing such as create a participatory arena with installation and performance.

Yi Wang (Cizzoe) | Triangle | 2024

Yi Wang (Cizzoe) | Triangle | 2024

Can you share a moment or experience that first inspired you to view human interaction as a game with its own rules?

The inspiration first came from observing everyday interactions between people. Since I was young, I’ve always enjoyed being an observer in a crowd, quietly watching how people behave and wondering why they act the way they do. I have a deep curiosity about how individuals present different versions of themselves in different groups, and what lies behind those shifting “personas.”

I began to notice that in various situations, people tend to play different roles, almost like a childhood game of role-playing. To stay connected and continue interacting, everyone follows a set of unspoken social “rules.” When someone leaves a group or joins a new one, new roles and new rules naturally emerge.

Of course, games can be both non-competitive and competitive. In some social settings, people seem to coexist peacefully on the surface, yet underneath there are personal motives, subtle self-interests, and even hidden forms of competition. What fascinates me is how these dynamics often happen beneath a mask of harmony. I see this as a kind of game because such behaviors arise when people enter certain groups or particular moments in time. There is always a sense of role-playing, sometimes a quiet competition behind masks. Wherever competition exists, rules follow, spoken or unspoken.

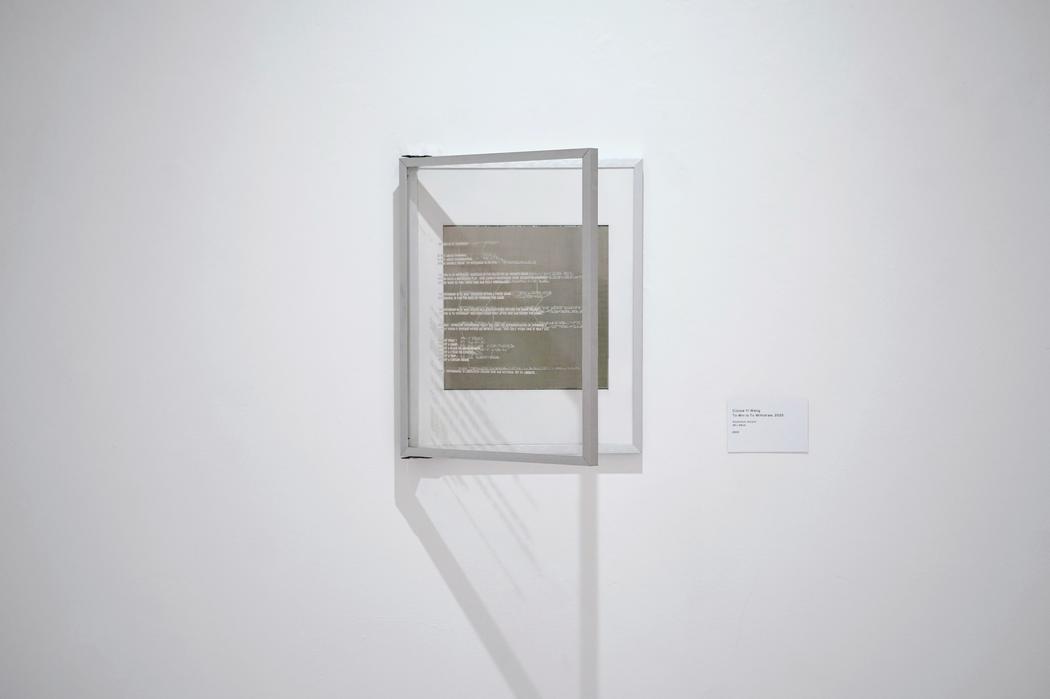

Yi Wang (Cizzoe) | To Win Is To Withdraw | 2025

Yi Wang (Cizzoe) | To Win Is To Withdraw | 2025

How did your transition from film practice to installation and performance unfold?

In my early documentary work, I began with an observational approach, spending a long time watching and recording how people behave and interact. Over time, I started to feel the limits of staying behind the camera. I wanted to step closer and enter the space of interaction. When I began engaging directly with the people I filmed and appearing in the frame myself, the conversations became more alive and revealing.

I realized that even when I tried to stay invisible, my presence still shaped the situation. So I chose to make that presence part of the work. By standing in front of the camera with my subjects, I invited the audience to observe both sides and reflect on our relationship.

This experience gradually led me to create my own settings for human interaction, where audiences could also step out from behind the screen and become active participants. I started writing instructions, creating interactive installations, and inviting people to perform together. Through these shared moments, I wanted to explore how real connection and quiet tension unfold between people, and within group dynamics.

The idea “To win is to withdraw” runs through your projects. What sparked this concept and how do you translate it into physical or performative form?

The idea developed gradually through a series of rule-based works. At first, I wanted to build interactive frameworks that mirror group dynamics, showing how our choices in society are often shaped or limited by the choices of others, and how we might find our own way within that inevitability.

My intention is to let the audience experience this concept rather than only understand it intellectually. In the work Triangle, where this idea first took shape, I set up rules and created an interactive installation that invites people to take part in a game, a temporary act of role-playing, where they can feel the concept and form their own reflections through participation and play. In the following work titled To Win is to Withdraw, instead of focusing solely on rational structures of rules, I sought to express the idea through poetic texts and sculptural forms, giving it both a tangible and emotional presence.

Yi Wang (Cizzoe) | Dancer Or Rope Holder | 2024

Yi Wang (Cizzoe) | Dancer Or Rope Holder | 2024

How do you hope participants will feel or think after engaging with this paradox of winning by leaving?

What I hope for is that participants leave with a sense of openness and release. The idea of to win is to withdraw begins from the condition that we are already inside a kind of loop, a situation of struggle, imbalance, or repetition. Choosing to withdraw offers an alternative path, a way to step outside of that cycle. It is not about failure, but about discovering another form of freedom.

Yi Wang (Cizzoe) | Them And Us | 2021

Yi Wang (Cizzoe) | Them And Us | 2021

Have you ever witnessed a surprising reaction or outcome when participants confronted this idea?

I’m not sure if it was a kind of confrontation to this idea, but there were moments when participants chose not to follow the given rules. Instead, they negotiated new rules within their own groups, in a more playful and lighthearted way. I actually enjoy witnessing these so-called moments of loss of control. They open up new layers of storytelling within the work and reveal how freedom can quietly emerge from within the structure of rules.

Yi Wang (Cizzoe) | Look To The Left Or Right, Or Neither | 2024

Yi Wang (Cizzoe) | Look To The Left Or Right, Or Neither | 2024

Many of your works create intimate spaces where strangers interact. How do you design the instructions to balance control and freedom?

For example, when creating the instructions for my work Triangle, I try to maintain a constant equilibrium between unity and division. Players come together in the middle, yet they are also competing against each other. In the game, there are moments when you have to control others in order to move yourself, while at the same time being controlled by your opponents. The key is that the game has no real ending, and the objective written in the instructions is to provoke group dynamics, where interaction, competition, and control remain in continuous flux unless someone chooses to withdraw. In this context, “winning” means withdrawing, when participants become aware of and consciously step out of a cycle that is no longer enjoyable or meaningful, where the desire to control and be controlled keeps repeating. From my point of view, that is the moment when freedom emerges.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.