Lisa Shtormit-Rommé

Where do you live: Paris, France

Your education: Film production design, contemporary art, curatorial practices, research into invisible art (France, Russia, Austria, Israel).

Describe your art in three words: mind games · memory · sensibility · alchemy

Your discipline: olfactory art, objects (sculptures) and installations, interactive projects

Website | Instagram

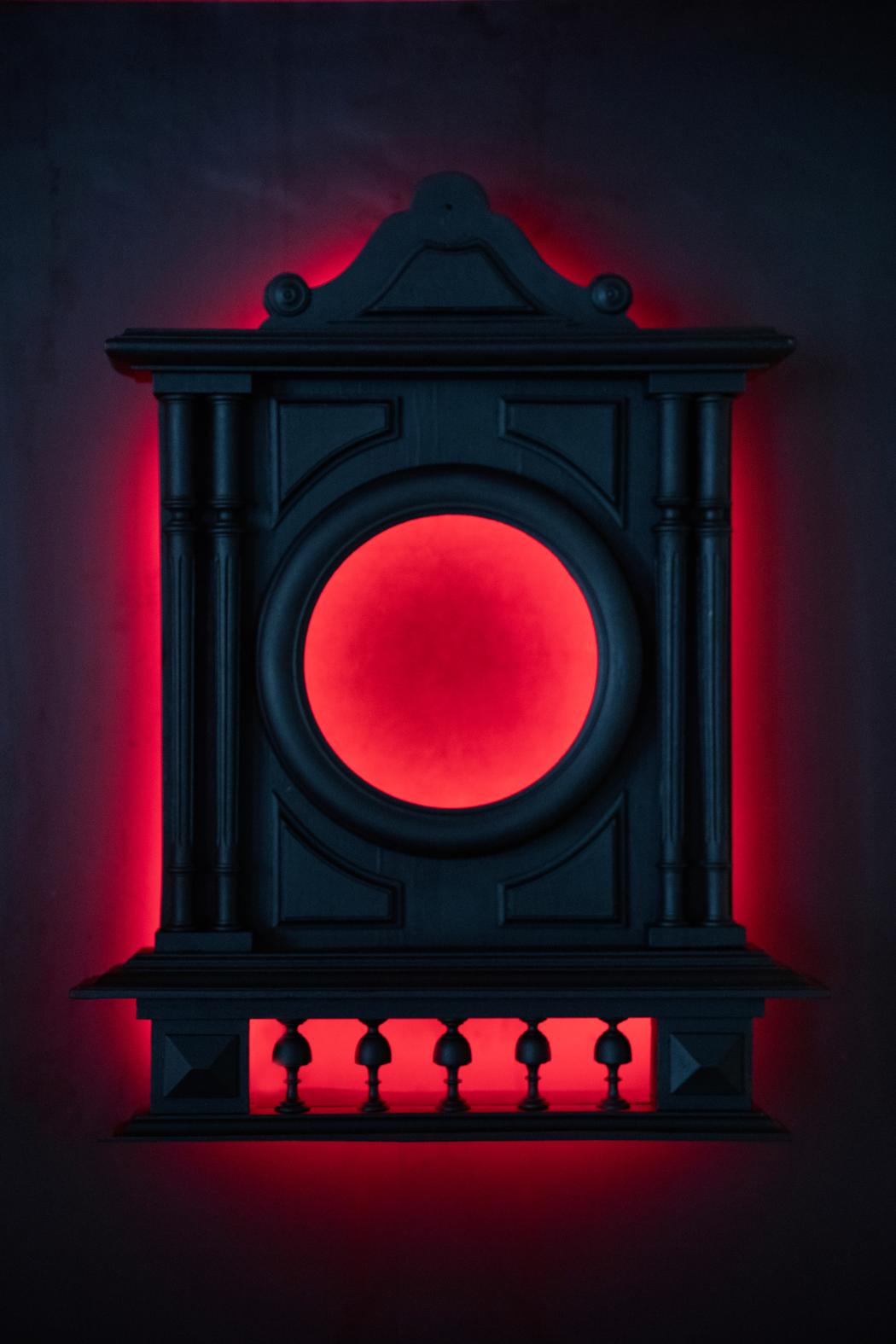

Lisa Shtormit-Rommé | Nosense | 2023

Lisa Shtormit-Rommé | Nosense | 2023

Your works often engage with olfactory elements. What drew you to explore smell as an artistic medium?

I’ve always been fascinated by experimenting with materials and exploring new, interdisciplinary territories within art. After receiving a classical academic education—where I studied almost every possible artistic technique—I felt the need to go beyond the familiar and find a language that hadn’t yet been exhausted.

When I began working in Russia, olfactory art was practically nonexistent, or at least unknown to me before 2016. So when I decided to work with scent on a regular basis, it wasn’t inspired by anyone else’s practice—it felt like discovering a new dimension. My first project using smell was created for the Jerusalem Biennale in 2016, entirely built around tactile and olfactory perception.

Since then, scent has become an integral part of how I think and create. I perceive the world through smell, color, and texture—form comes later. Even when I paint, make objects, or stage performances, there is always a reference to fragrance.

Scent is among humanity’s most ancient forms of communication. It acts on instinct, bypassing logic and reason. While we receive around 80% of our information visually, smell reaches the brain fastest, triggering memory and emotion. A scent itself is neutral; it becomes “pleasant” or “unpleasant” through personal experience, cultural memory, or emotional context.

This invisible magic fascinates me. From ancient rituals of embalming to the burning of incense in temples, fragrance has always accompanied humankind. Frankincense, for instance, is unique—it truly enters our lungs and, symbolically, our soul.

My work draws on the histories of alchemy, perfumery, pharmacy, and early medicine. I see olfactory art as a way to speak about time, faith, and human experience. Scientifically, olfactory memory is the longest-lasting kind of memory; one familiar scent can instantly transport us to another place and time. Isn’t that a form of magic?

I create most of the scents for my works myself, and when the composition is particularly complex, I collaborate with professional perfumers. I also collect what I call “unclassified olfactory installations”—artworks that contain a scent but are not officially presented as olfactory art.

Ultimately, this path led me to study what I call “the invisible arts” during my time in France—a field dedicated to everything that exists just beyond the edge of perception.

Lisa Shtormit-Rommé | Saturnus | 2023

Lisa Shtormit-Rommé | Saturnus | 2023

How do you think memory and smell are connected in your work, particularly in the ‘nOsense’ project?

The nOsense project was postponed several times due to the pandemic, and by the time it began, my residency at ACME London coincided with strict lockdown measures. I found myself in a city I could neither truly see nor experience. The initial idea was to collect tactile and olfactory impressions of London as a foreigner—but under isolation, such impressions became almost impossible.

Smell became my only means of sensing presence. The only public spaces accessible during lockdown were churches—spaces filled with the scent of stone, incense, and silence. Through them, I realized that memory can arise not only from lived experiences but also from their absence. nOsense became a reflection on emptiness, on the impossibility of remembering when there is nothing to remember, and on scent as the final link between the body and the passage of time.

Lisa Shtormit-Rommé | nOsense | 2020

Lisa Shtormit-Rommé | nOsense | 2020

Can you explain the significance of the symbolism in your pieces, such as the use of colors and materials like black velvet and red neon?

The materials I use are chosen not only for their visual qualities but for their ability to retain and transmit scent. Texture and porosity matter as much as form. Velvet, for instance, absorbs and holds fragrance exceptionally well. It also carries a deep cultural charge — traditionally associated with monarchy, the church, and luxury — symbols that resonate on a subconscious level.

My color palette is intentionally minimal and symbolic. Red is the dominant hue: a color of life, blood, passion, and awakening, but also of tension and alertness. It activates perception and draws the viewer into the work physically and emotionally. Black, by contrast, is absorptive and introspective — the color of silence, mourning, and the unknown.

Neon, particularly red neon, functions as a sculptural light source. It creates an atmosphere of mysticism and suspension, as if the object hovers outside the laws of gravity. The dialogue between black velvet and red neon embodies the tension between the tangible and the immaterial, between the body and the spirit.

In your immersive installations, you mention that the audience becomes an active participant. How do you intend for the viewers to interact with your work?

In many of my projects, I use elements of gamification — I invite the viewer to play: to open a door, to smell, to guess, to touch, to read, to speak. These simple gestures become the key to understanding the work. I want the viewer not to merely observe but to explore, to question, to engage in dialogue.

Scent itself is a provocative medium. It instantly evokes memories, and many visitors begin to share deeply personal stories — about childhood, loss, pain, or love. The aroma becomes a bridge between the artist and the audience, creating a space of trust. I see my role as accompanying the viewer gently through that emotional journey.

As a teacher and curator, I’ve often wondered why so many people are intimidated by museums. Perhaps because everything there feels too formal, too strict, too “forbidden.” My installations aim to break that distance, to bring back a sense of direct, physical connection. Yet I also value context and education — freedom in art must coexist with respect for it.

Some of my early works were built like puzzles: viewers had to guess what was hidden inside before discovering it. In these moments, the adult becomes a child again — curious, playful, alive. They crawl under tables, search for clues, recite poems, argue, and laugh. It’s not just interaction; it’s a rediscovery of sensitivity.

For me, gamification in art is a simulation of real life — a space where people practice being themselves. To sense, to wonder, to respond. That, perhaps, is the true participation my work calls for.

Lisa Shtormit-Rommé | nOsense | 2020

Lisa Shtormit-Rommé | nOsense | 2020

In your ‘Saturnus’ installation, you focus on ancient rituals and astrological symbolism. How does this tie into your exploration of time and existence?

Saturnus is a meditation on time as a living, almost tangible substance — heavy, cyclical, and irreversible. For me, it’s not merely an installation but an inquiry into how ancient rituals and cosmological beliefs shaped humanity’s sense of existence. In that way, I see art as a form of modern alchemy — a practice that bridges the material and the spiritual, the rational and the intuitive.

I don’t believe that everything lacking scientific proof is meaningless. Ritual practices across cultures and “magical thinking” were often tools of survival and understanding. What we now call superstition was, in many cases, an early form of knowledge — a different epistemology. The absence of evidence does not necessarily mean the absence of essence.

In Saturnus, time becomes both subject and metaphor. Like the mythological Saturn devouring his children, time consumes everything it creates. It’s slow, dense, and inescapable — a reminder of human limitation and accountability.

My research often intersects with various disciplines — from chemistry and physiology to forensic science, psychology, and pharmacopoeia — but also with their more speculative counterparts: alchemy, astrology, mythology, and healing traditions. I’m interested in how myth and ritual continue to shape our perception of the world. Contemporary art, in a sense, is just another form of myth-making — and within that framework, Saturnus exists as both question and ritual.

Lisa Shtormit-Rommé | nOsense | 2020

Lisa Shtormit-Rommé | nOsense | 2020

What do you hope the viewer experiences when engaging with your work, particularly in terms of sensory and emotional responses?

I have quite a lot of first-hand observations — I often invite visitors to write in the guestbook, to describe what they felt, saw, or remembered. During exhibitions, I like to talk to people directly, to watch how they enter the space, how their body reacts — the pause, the breath, the shift in posture.

Many describe a sense of harmony, aesthetic pleasure, and fascination. They are drawn to the mystery of the installations, comparing them to cabinets of curiosities — spaces that invite slow looking and exploration. I often see them captivated, surprised, or quietly delighted.

At some point, they seem to return to a childlike state — curious, sincere, and emotionally open. For me, that’s the most meaningful response an artwork can evoke: when a person forgets to “analyze” and simply allows themselves to feel.

Of course, olfactory art cannot truly be experienced through images — scent is its living essence. Yet even through sight alone, one can perceive the atmosphere, that invisible vibration that binds form, material, and emotion into a single sensory moment.

Lisa Shtormit-Rommé | Les Sans Dents | 2024

Lisa Shtormit-Rommé | Les Sans Dents | 2024

You have worked in various art residencies. How have these experiences influenced your approach to curating and creating installations?

Residencies have taught me to adapt quickly, to conduct focused research, and to create with whatever materials and conditions are available. They trained my ability to see opportunity within limitation — to find, connect, and stay curious. This curiosity toward other cultures and ways of seeing the world has become an essential part of my artistic method.

Every residency adds another layer of perception. Everything we see, absorb, and experience becomes part of an inner archive that later unfolds in our work. The broader one’s exposure, the more nuanced and complex the creative outcome — like a multilayered mixture of meanings, scents, and textures.

Art residencies are a time when I am completely focused on myself and fully immersed in my work. They are an excellent tool for limiting time and a kind of challenge. I would advise every artist to visit an art residency and discover their potential in new circumstances. I have visited nine art residencies, some of which taught me to quickly find information, conduct research, build communication with new art communities on site, and, of course, study the traditions, history, languages, prejudices, and legends of the place. All of this has developed and enriched my art practice.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.