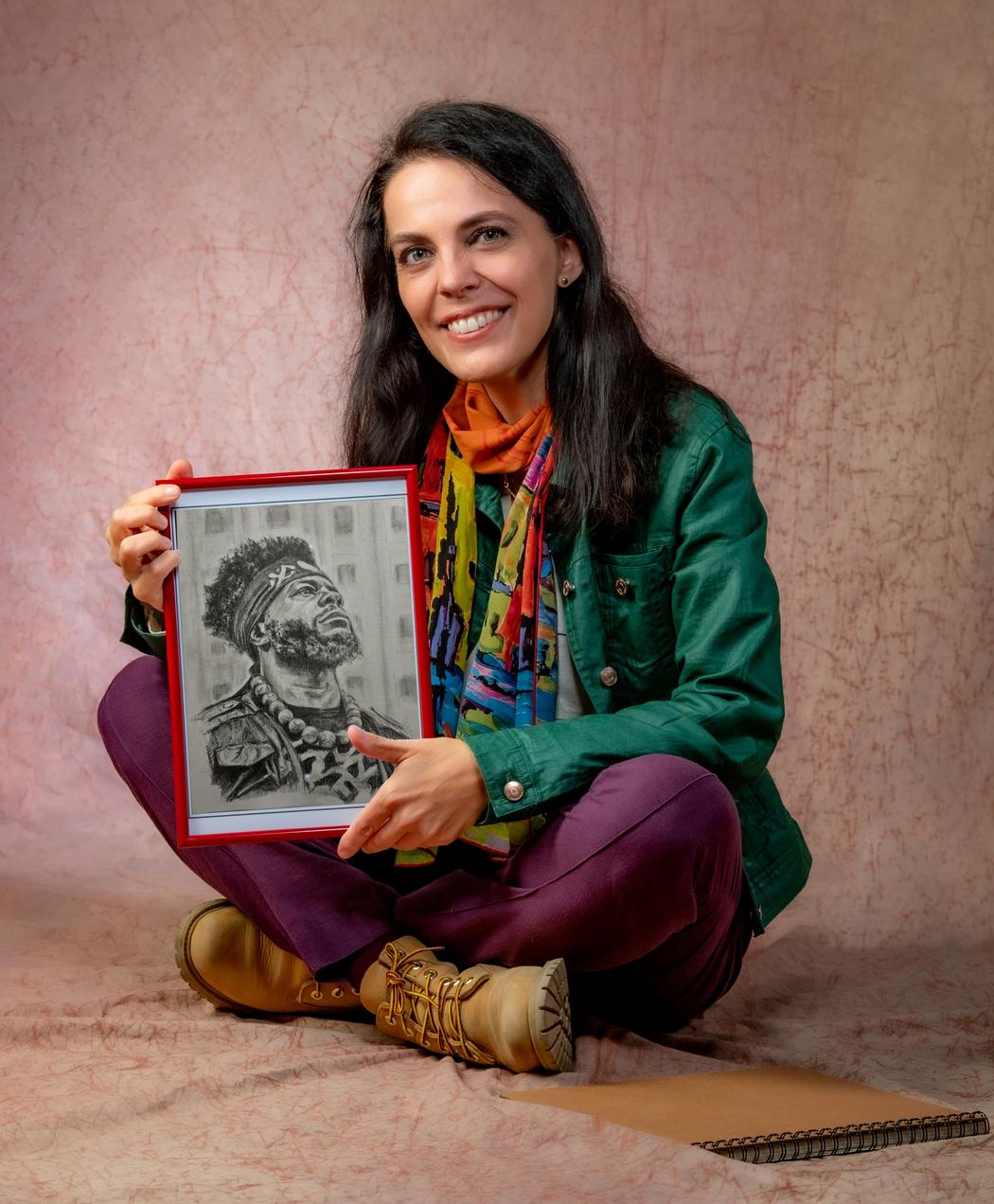

Magdalena Brzezinska

Your education: M.A. in English Philology (Linguistics), working towards Ph.D. in Linguistics

Describe your art in three words: raw, empathetic, introspective

Your discipline: dry media drawing

You returned to art after many years, at a different stage of life. How did this return change your understanding of yourself as an artist and as a person?

I returned to artistic creation after decades, when my three children were no longer small and dependent. The return was a demanding and lengthy process. At first, I felt disheartened by my lack of practice and technical imperfections. Years without art had left me acutely aware of my shortcomings, which were difficult to bear because of my perfectionism. Comparing myself to others wasn’t helpful, either. Yet, certain poignant events in my private life sensitized me to life’s fragility and its one-time nature, so I decided to persist, and my children supported me in this journey. Gradually, I became more accepting of my deficiencies and of the fact that the conditions for creating are less than ideal. Often, my studio is my bed, with all the materials scattered around. I am still in the process of discovering my artistic voice. I cannot say I am very lenient toward myself, but I am becoming bolder and more forgiving of the unsuccessful attempts.

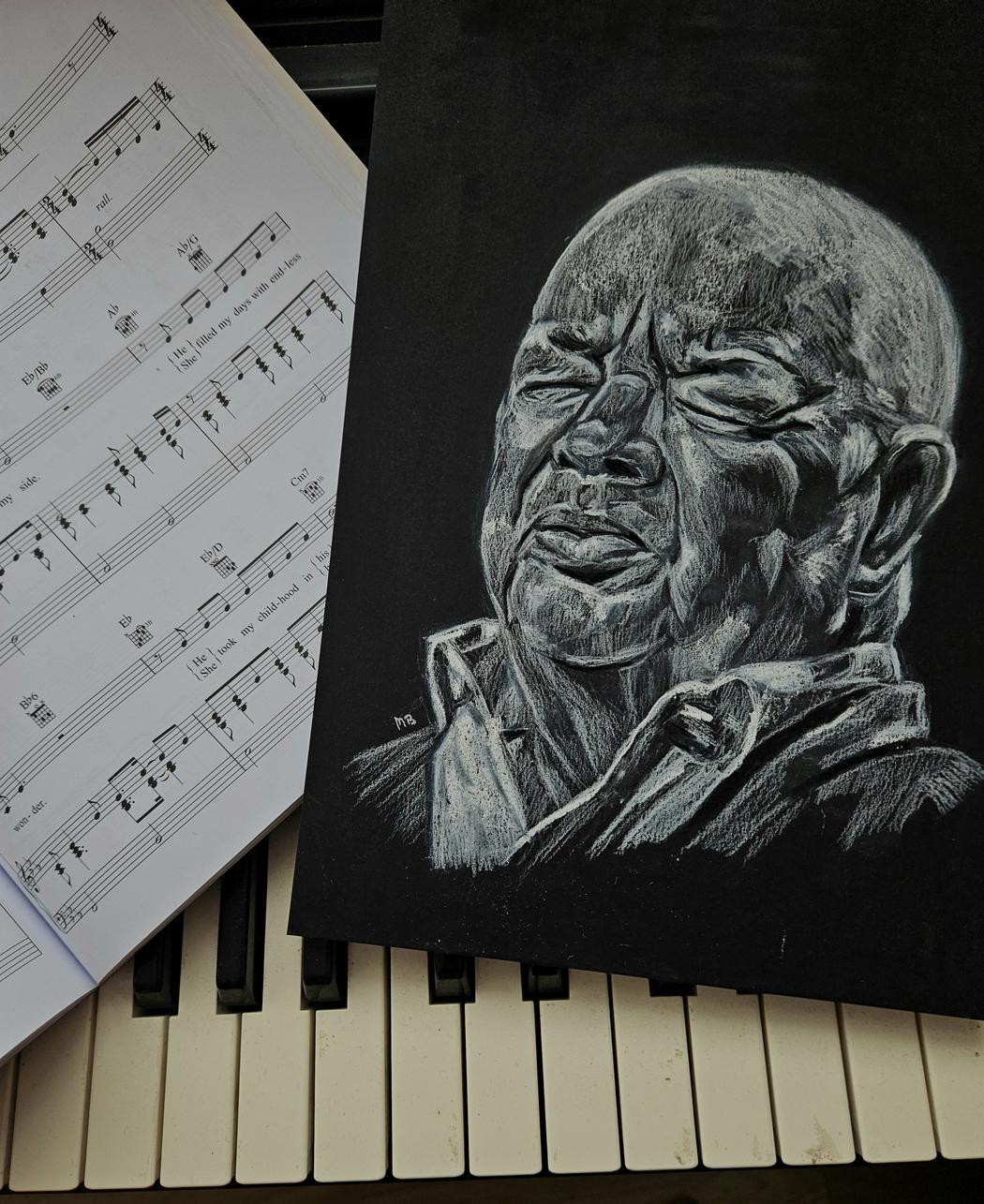

Magdalena Brzezinska | Stanislaw Soyka | 2025

Magdalena Brzezinska | Stanislaw Soyka | 2025

You have said that a portrait is a journey into the model’s soul. How do you sense or approach this “unspoken” inner layer when you work?

This is a very difficult question, as I am not fully aware of how this happens. What I know is that for me, a portrait is a lot more than capturing a likeness, even though it feels nice when viewers recognize the model. I mostly sense and intuit the model’s energy, emotional state, and the silent stories that may want to be revealed. I like discreetly observing people in public places, on trams, in cafes, or in waiting rooms. I try to imagine what may be going on in their minds. Connections come naturally to me, so sometimes observation is followed by a conversation. Working on a portrait also feels like a meaningful dialogue, or perhaps even more so, like listening: to faces, particularly to eyes and whatever they reflect. Still, I accept that sometimes I may read emotions into people that are just my projections. Ultimately, art is about interpretation, so I give myself and the audience the right to speculate.

Magdalena Brzezinska | Louis Armstrong | 2025

Magdalena Brzezinska | Louis Armstrong | 2025

Male faces appear frequently in your work. What do you find emotionally or visually compelling in masculinity, aging, and the marks of time?

I am drawn to rawness, to faces allowed to be imperfect and age. What is shaped and warped by time interests me far more than what is smooth, generic, or perfected by expectation. Men have always had a freedom that I long felt society denied women: the freedom to be flawed, weathered, and elderly. And wrinkles, fatigue, and roughness carry stories: narratives that can take your breath away or humble you. I also like discovering vulnerability in strength and tenderness in apparent coarseness, which, I feel, is easier to see in male faces. Finally, while I mainly manifest my femininity, I also recognize a strong presence of cross-gender characteristics in myself, and I am on a constant quest to unravel the masculine element in me.

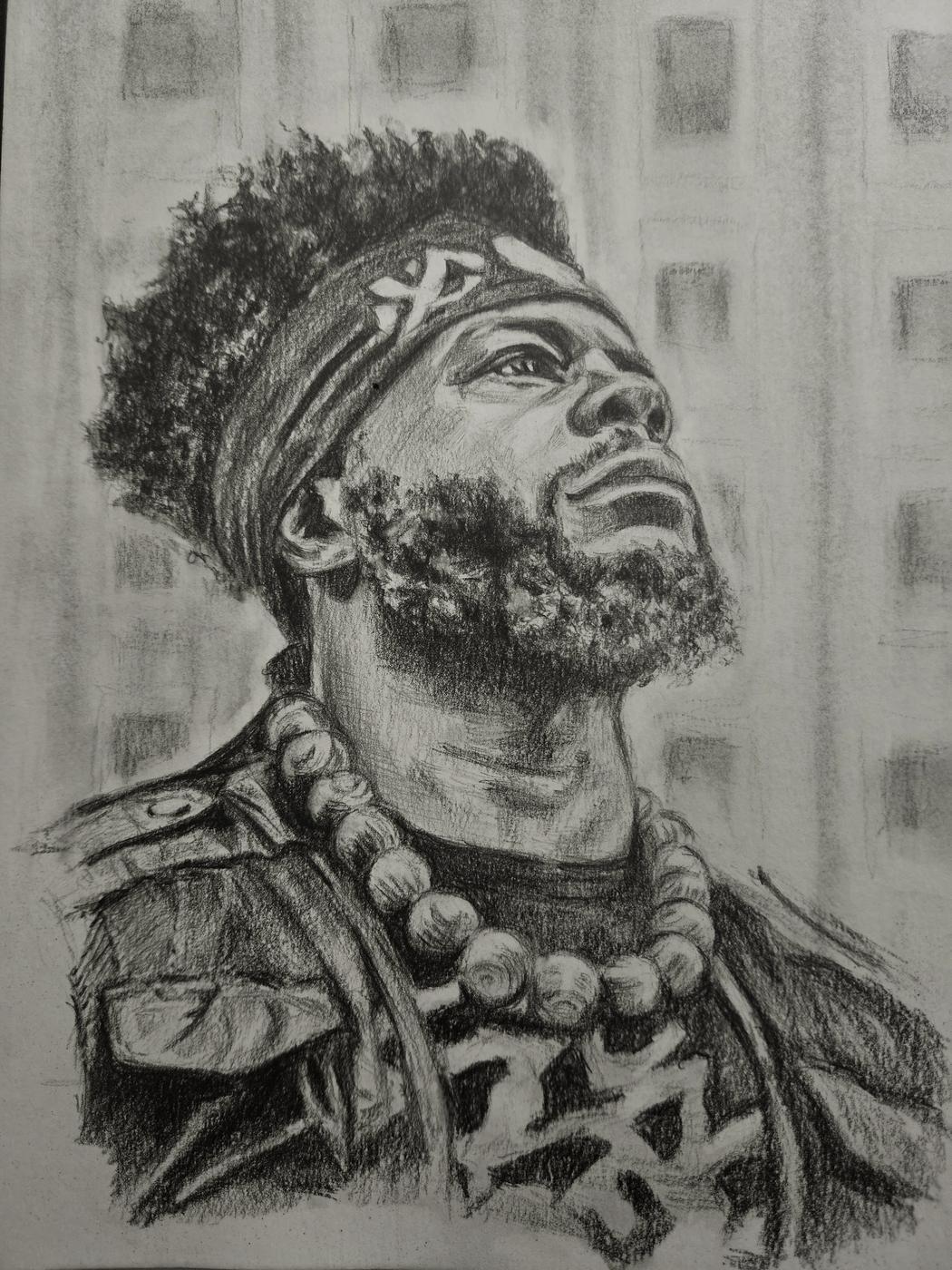

Magdalena Brzezinska | Blackwatr | 2025

Magdalena Brzezinska | Blackwatr | 2025

In this portrait, reflections in sunglasses play a crucial role. What made reflection an essential narrative element rather than a secondary detail?

The reflection was definitely the trigger for taking the photo that later served as a reference for the pastel painting. Although I was never quite as brave as Julia Margaret Cameron, Dorothea Lange, or Diane Arbus, these seminal artists inspired me to look at people closely and try to capture transient and occasionally intimate family moments. The photo, and then the painting, was never only about my son’s face, but also about what appeared briefly within its frame. Transience played an important role. My daughter and I are only temporarily present, visible for as long as Albert’s attention lingers. Thus, our presence is already becoming a disappearance; the here-and-now is already turning into the past.

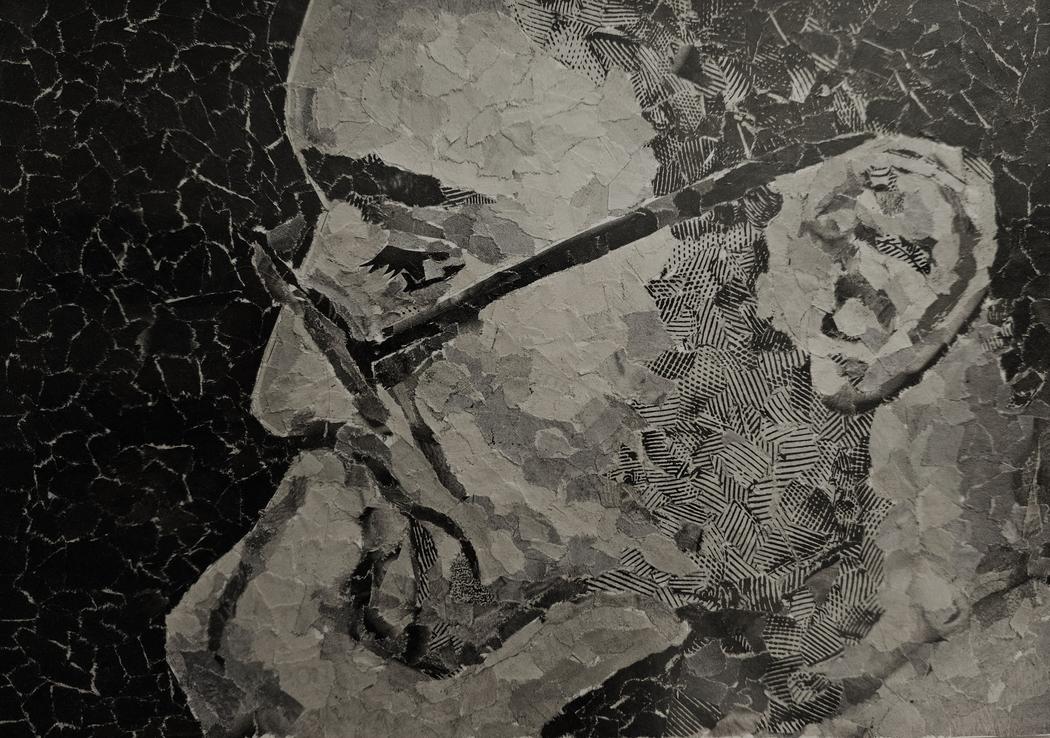

Magdalena Brzezinska | Passenger | 2025

Magdalena Brzezinska | Passenger | 2025

The image captures not only your son, but also you and your daughter reflected in him. How conscious were you of memory, loss, and distance while creating this work?

I was conscious of distance and loss both in the moment of capture and later, during the act of drawing. I liked the mirrored glasses and the fact that even though my daughter and I were reflected in them, I could not be really sure what my son was looking at. Albert was a teenager who suddenly outgrew me physically, and I was not quite ready for that. He was towering over the petite us, and I was aware that even though all three of us were close then, this was already a prelude to him becoming his own, independent person living a separate life: a difficult truth for many mothers. Last December, as I was rendering the image in pastel, I was reliving the moment. The portrait became a record of our three lives briefly aligned, all the more precious now that my son has started his own family and my daughter lives far away.

Magdalena Brzezinska | Jacek | 2013

Magdalena Brzezinska | Jacek | 2013

You work primarily with pencils and dry pastels, sometimes using iridescent pigments. What does this combination allow you to express that other media might not?

Graphite and dry pastel used against rough paper suit my temperament and my way of seeing reality. Life is rough, so coarseness should be felt when it is being expressed. That is why painting as a way of expression has no allure for me. I admire the old masters of chiaroscuro: Rembrandt, Caravaggio, or de La Tour, and they inspire me beyond my humble abilities, but a brush does not feel right in my hand. Also, pencils and dry pastels allow for hesitation, correction, and uncertainty, which soothe my perfectionism and are essential to how I work. As for the iridescent pigments, they lend a face a glow, a subtle light that illumines everyone coming into this world. I want to discover it even in the toughest faces.

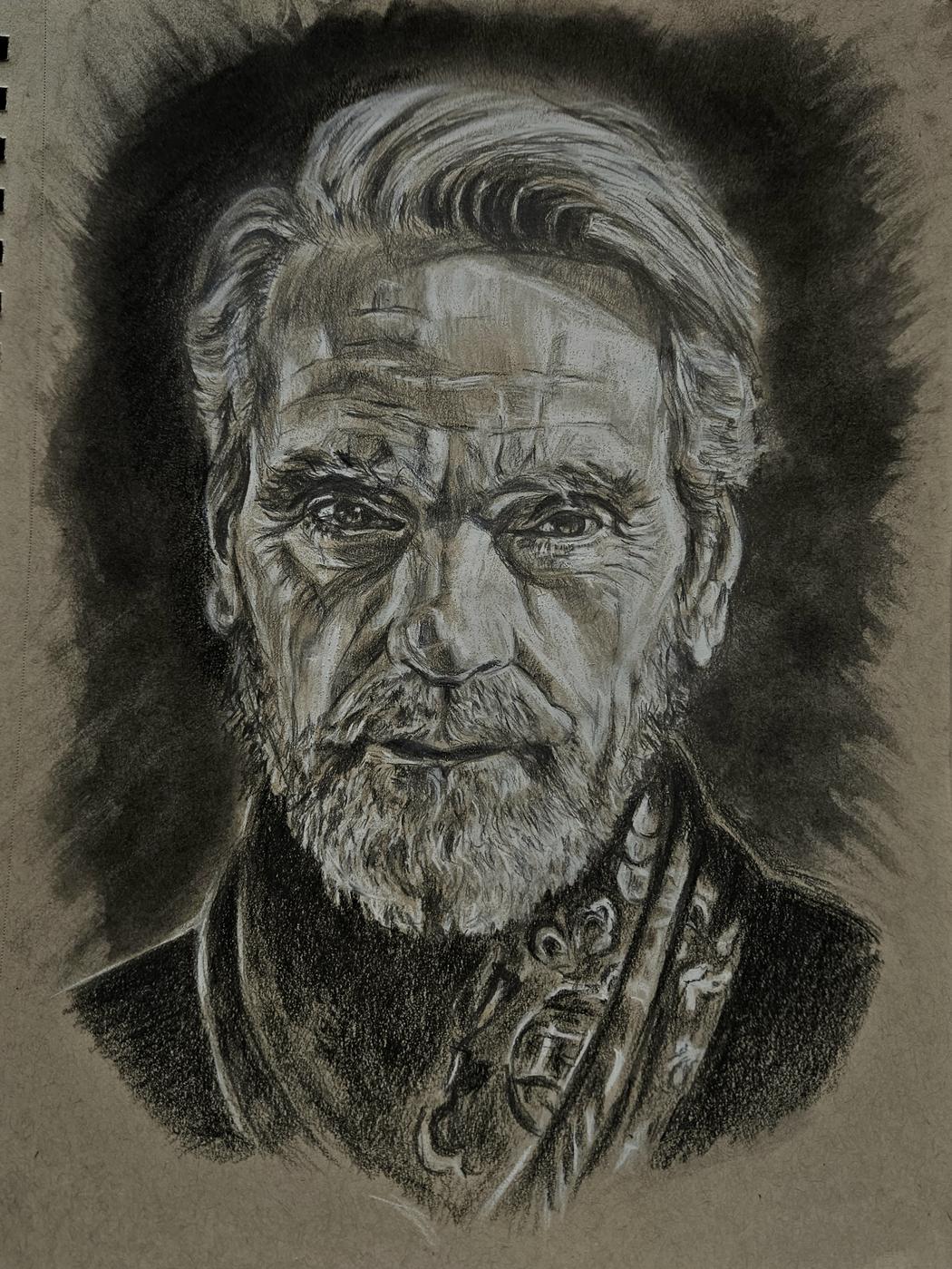

Magdalena Brzezinska | Jeremy Irons | 2024

Magdalena Brzezinska | Jeremy Irons | 2024

Your background includes art therapy. Does this experience influence how you relate to your subjects or to the emotional depth of your portraits?

I have never given it much thought, but I feel that my training in art therapy, as well as my natural empathy, may deepen my sensitivity to the layers beneath our appearance. We are fragile, here today and gone tomorrow. Our faces endure, survive, and remember. I want my portraits to be attentive rather than judgmental. I want to honor fatigue, imperfection, and vulnerability. I do not avoid portraying people who are young, strong, and beautiful, or so they seem, but I am aware of ephemerality. It may sound like a cliché, but I want to actually see people, not just look at them, and allow their inner life to emerge on paper.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.