Aazam Irilian

Aazam Irilian | Celestial Landscape

Aazam Irilian | Celestial Landscape

Your work often explores the intersection of nature, memory, and invisible forces. When did you first become aware that these themes were central to your artistic language?

I’ve always been a reflective person, constantly examining not only my life but also my art. Over the years, I noticed a common thread running through all my work—a sense of otherworldly presence, whether in the void of space or the quality of light at dawn and twilight. These moments mesmerized me, and I kept returning to them without fully understanding why.

More recently, I recognized that the mystical dimension in my work stems from my cultural background. I was born in Iran and grew up in a culture where poets like Rumi, Hafiz, and Saadi are revered—their collected works found in almost every home, their verses memorized and used as everyday proverbs, recited during Nowruz and other celebrations. People seek guidance from Hafiz’s verses by opening his Divan for wisdom during life’s important moments. This isn’t just literature—it’s a living spiritual practice woven into the fabric of daily existence.

Understanding this connection—recognizing where my impulse toward the mystical and invisible came from—gave me clarity about my artistic voice. It not only made me comfortable sharing this aspect of my work openly, but it also made me a more intentional and confident artist. I stopped questioning these tendencies and instead leaned into them as my inheritance and my strength.

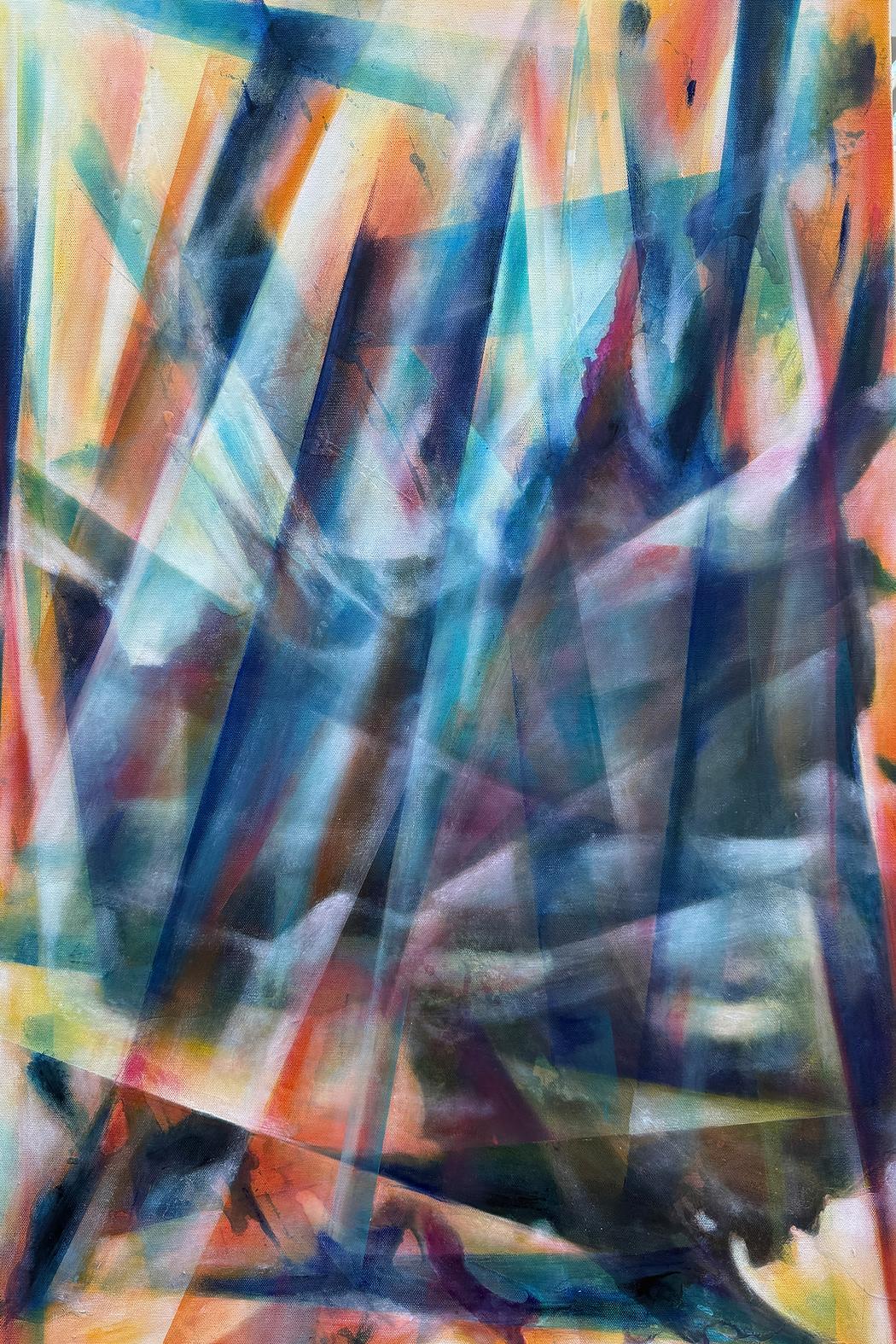

You describe the veil as a threshold between visible and invisible worlds. How does this idea translate visually in your layered and translucent compositions?

Science is just starting to catch up with what Indigenous cultures have known for centuries. Shamanic practices allow spiritual leaders to tap into a consciousness that couldn’t be explained or understood through conventional frameworks—hence the negative view these practices often received. Shamanic journeys, dreams, and visions were described as passing through a veil where light expanded and there was a sense of unlimited love and connection.

In recent years, physicists have begun discussing the possibility of a multidimensional universe and multiple realities existing simultaneously. Whether we’re talking about Indigenous wisdom or quantum physics, none of these worlds are visible to our physical eyes—they remain veiled from our ordinary vision.

Being intrigued by these ideas and experiences, I started envisioning how light might move through these hidden dimensions. My goal was to create a sense of depth that isn’t based on mathematical perspective but on something more visionary—closer to atmospheric perspective, where layers of air and light create distance and mystery. By building thin layers upon thin layers, I’m able to show this kind of depth. As the layers accumulate, some areas become more dense and opaque while others remain translucent, creating a sense of looking through or beyond. Each painting is different, but some can have over a hundred layers of paint applied gently and thinly to achieve the effect I’m searching for—that sense of peering through a veil into something just beyond our sight.

Aazam Irilian | First Dance Of Light

Aazam Irilian | First Dance Of Light

Your process embraces spontaneity, surrender, and chance. How do you balance intuition with intention while working with unpredictable materials?

I begin every piece by pouring thin layers of fluid paints onto the canvas. The colors are selected intuitively, without attachment to a specific outcome. This process allows the colors to move freely and interact with each other, creating a layered ground that I have no control over. From there, I start building additional layers, developing the sense of light moving through these invisible worlds. Throughout the painting process, I allow the piece to guide me toward what comes next.

There have been times when I feel lost, and I sit meditating, asking the piece to show me the next step—and most often, I can see what needs to happen. But I’m also a trained professional artist, so at a certain point my technical knowledge and education come into play. I begin to take more control, ensuring the piece is balanced, the colors are harmonized, and I’m achieving the sense of depth and dimensionality I’m searching for.

It’s a dance between surrender and skill—the initial layers are about letting go and trusting the process, while the later stages require me to step in with intention and compositional understanding.

Aazam Irilian | Infinite Realms

Aazam Irilian | Infinite Realms

You often use mineral solutions and salts to create texture. What draws you to these materials, and how do they contribute to the dialogue between art and science in your work?

Originality was the main reason I started experimenting with a variety of household materials—coffee, salt, sugar, and more. It was by accident that I learned how salt solution interacts with paint to create intriguing textures. “Crystal Cove” was the piece where this transition began. From that point, I started asking the “what if” question and began experimenting with other minerals. I would make solutions with different saturations and use them like another painting medium. Each mineral reacted differently on the surface, creating distinct and exciting textures. This is a crystallization process that depends heavily on humidity and atmospheric conditions—the crystals are alive in a sense, changing with the weather.

That experimentation taught me so much about letting materials have their own voice and surrendering control to natural processes. While I’ve moved away from working with minerals in my current bodies of work, that period of exploration deepened my understanding of how art can reveal invisible forces at play. It opened doors to new ways of thinking about layering, texture, and the dialogue between intention and chance—principles that continue to inform everything I create.

Aazam Irilian | Rapture | 2025

Aazam Irilian | Rapture | 2025

Many of your paintings feel like portals or spaces for contemplation. What kind of experience do you hope viewers have when standing in front of your work?

I believe art can be a vehicle for change—socially or spiritually. My work is focused toward the latter. My goal is to bring a sense of calmness and beauty into this world, to create something that intrigues viewers enough to stop and truly engage with the piece.

I see my paintings as invitations to pause and reflect on what lies beyond the visible—visual portals into the vastness of the natural world and the mysteries that connect us to it and to each other. In our fast-paced, overstimulated world, we rarely give ourselves permission to simply be present and contemplate. If someone can stand in front of one of my paintings and experience even a moment of stillness, of wonder, or of connection to something larger than themselves, then the work has fulfilled its purpose.

I’m not trying to tell viewers what to see or feel. Instead, I hope to create an opening—a space where they can bring their own experiences, memories, and questions. The translucent layers, the sense of light moving through space, the depth that suggests other dimensions—these are all meant to invite a meditative state, a slowing down, a looking inward as much as outward.

Aazam Irilian | Liminal Spectrum | 2025

Aazam Irilian | Liminal Spectrum | 2025

Having exhibited internationally and across the United States, do you notice differences in how audiences from different cultures respond to your work?

Through my experiences and interactions with people from different countries and cultures, I’ve learned that we are more similar than different. We might speak different languages or hold different beliefs, but at our core, most people are looking for connection, meaning, and a sense of calmness in their lives. This is no different when it comes to viewing art—mine or anyone else’s.

Regardless of location, I hear similar responses from those connecting to my work: “otherworldly,” “spiritual,” “like stained glass,” “meditative.” These words come up again and again, whether I’m exhibiting in California or across the ocean. During a recent trip to Italy, a curator told me my work would look beautiful exhibited in a cathedral—which speaks to that sense of sacred space and contemplation people seem to find in the paintings.

One moment that moved me deeply was when a professor at Antelope Valley College, where I had a solo exhibit, told me that he often finds students sitting in front of my paintings in the morning, meditating. That comment brought tears to my eyes—what could be better than making that kind of connection with the younger generation?

Similarly, at a recent exhibition in France, there was a sense of genuine surprise and delight from viewers. One older man told me, “This is the first time I understand abstract art.” What a compliment!

These experiences have confirmed what I’ve always believed—art doesn’t know boundaries. It speaks a universal language that transcends culture, geography, and even age. When the work creates that moment of pause, that opening for reflection, it resonates the same way whether someone is standing in front of it in Los Angeles, France, or anywhere else in the world.

Aazam Irilian | Shattered Dawn

Aazam Irilian | Shattered Dawn

As both an artist and an educator, how has teaching influenced your own creative practice over the years?

Teaching has taught me patience and reinforced my belief in the value of artistic training—not as a barrier, but as a tool that expands creative possibilities.

I’ve always believed that creativity doesn’t know boundaries—anyone can be creative, and I teach that wholeheartedly. At the same time, I’ve seen how understanding the foundational elements and principles of art and design can transform someone’s ability to express what they’re envisioning. This was confirmed through my students semester after semester. New groups would arrive in my classroom eager to express themselves freely, and I would ask them to give me ten weeks to learn about the elements and principles of art and design. They still had creative freedom, just with some new tools in their hands. After those ten weeks, the look of pride in their eyes told the whole story—they could see the difference in their own work.

Today, I still hold workshops on creativity that focus on expression, feelings, and the healing process rather than formal art education. That work is deeply meaningful and serves a different purpose. But for those who want to develop their technical skills further, I offer a more academic approach. Both paths are valuable—it simply depends on what someone is seeking from their creative practice.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.