Anastasiia Lodde

Where do you live: Denmark

Your education: 2017 PhD Fellow in Genetics, Koltzov Institute of Developmental Biology

Describe your art in three words: observational, human-centered, transformative

Your discipline: visual artist (painting, installation, performance)

Website | Instagram

Your background is in genetics, and you spent many years in science before transitioning to art. How has scientific thinking influenced the way you construct narratives and symbols in your paintings?

Science taught me to observe, think systematically and understand that even the smallest element can carry meaning within a larger structure. I approach symbols like variables in an experiment: they repeat, mutate and shift context over time. I create visual ecosystems where symbols interact, recur and evolve and this mindset lets me work intuitively while staying attentive to the internal logic, rhythm and cause-and-effect relationships within an image.

I spent many years working in genetics, creating transgenic organisms like wheat and sunflowers, altering biological elements so that new forms could emerge. Looking back, I realise I still do something very similar in my art. I’m capable of processing large amounts of information — personal memories, historical layers, everyday observations — and when all of this passes through my emotional sensibility, it becomes an image. This is where the story begins.

Perhaps this is why I create anthropomorphic fish and hybrid objects and why my themes keep flowing into one another. I combine fragments, allow meanings to shift and let one form transform into another. For me, art is a space of controlled transformation, where analysis dissolves into emotion and something new is born.

Migration and displacement are central themes in your work. At what point did you realize that these experiences would become the core of your artistic language?

After moving to Denmark, I began painting more consciously and intensely. At the same time, I felt a growing need to look back. I gradually realised that I knew almost nothing about certain parts of my family history and this absence itself began to trouble me.

This curiosity led me to work with archives and to contact Estonian archival institutions in order to learn more about my family. Through this research, I discovered a recurring pattern of migration shaped by repression and forced displacement.

When I later experienced migration myself, it was a voluntary choice and this difference became very important to me. As I went through the stages of migration — disorientation, fragmentation, gradual transformation — I felt these processes in my own body, but I was also able to see them from another angle: as an opportunity for growth and personal enrichment.

Painting became both a form of therapy and a space for reflection. Over time, my practice expanded beyond my own history. I began listening carefully to the experiences of friends and people around me, carrying their stories with care. What began on canvas has since evolved into installations and performance, allowing these multilayered personal and collective experiences of migration to coexist in a shared space.

Fish, bicycles, suitcases, and Soviet-era objects recur throughout your paintings. How do these symbols function for you – are they personal memories, collective signs, or evolving metaphors?

They all began as deeply personal images rooted in memory, but over time they stopped functioning as fixed symbols and became something more fluid.

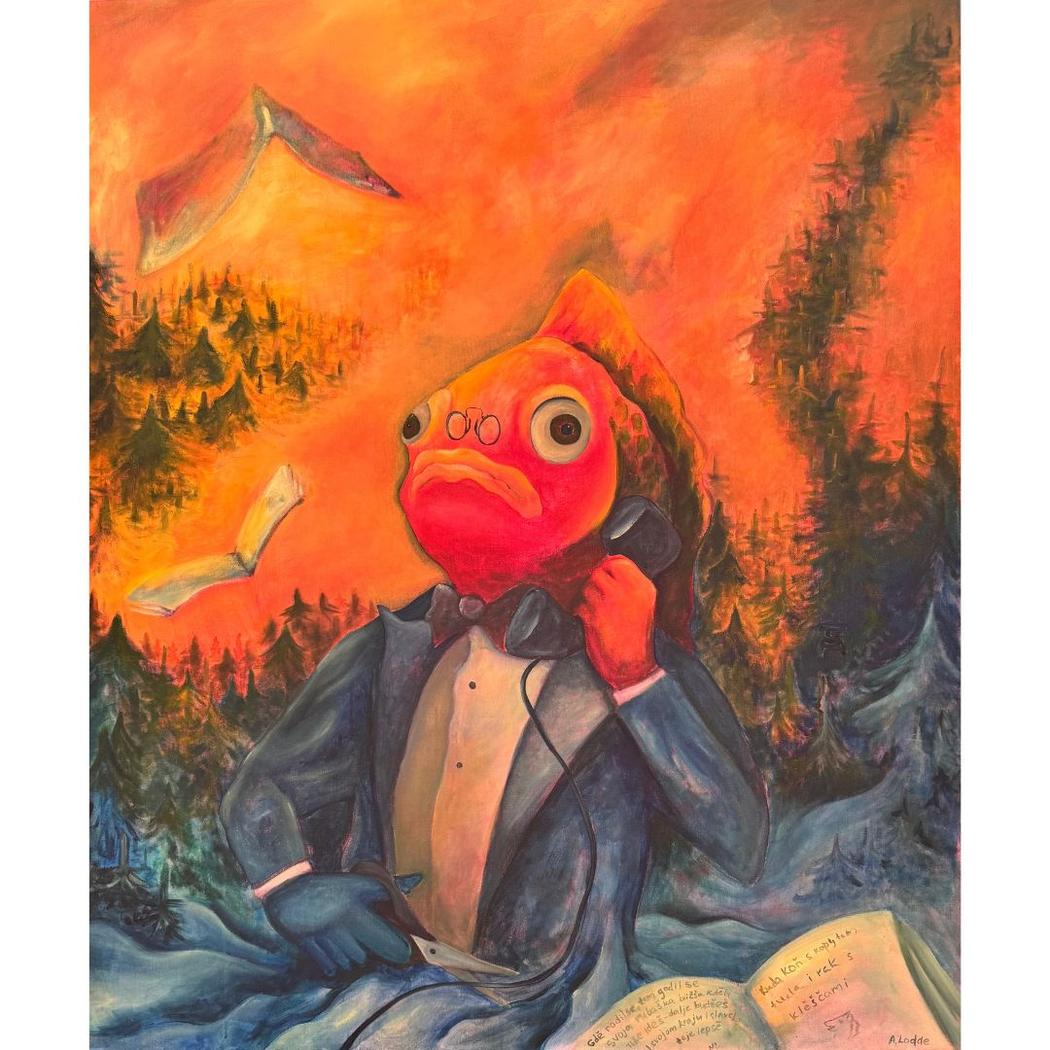

The fish, for example, first emerged as a symbol of inner values. It comes from my childhood: I grew up near a river and spent many hours fishing with my grandfather. Gradually, though, the fish began to change. It didn’t simply become a figure of a migrant; it started to transform into a human-like presence. Today, the fish in my work carries fears, desires, contradictions and impulses. It is neither good nor bad. It exists with all the complexity of being human and sometimes with traces of inhumanity. This ambiguity matters to me. I’m interested in moments when the boundary between human and non-human becomes unstable.

Other recurring objects — bicycles, suitcases, houses — function in a similar way. They are rooted in personal memory, but they also belong to a shared cultural and historical experience. Over time, they become vehicles of movement and adaptation. I allow these elements to evolve without fixed meanings; they grow alongside me, absorbing new layers of experience. In this sense, my symbols are living forms, always in the process of becoming.

You describe your practice as working through a post-migrant lens. How has living and working in Copenhagen reshaped your sense of identity and artistic voice?

Copenhagen gave me security, distance and enough time to reflect on my life and ask myself who I am and why I’m here. In many ways, it allowed me to live a second life. With familiar structures gone, my sense of identity narrowed to survival and day-to-day decisions. Long-term planning seemed impossible and much of my energy went into managing uncertainty.

Around 2021–2022, during a very intense emotional period, I became acutely aware of how fragile identity can be when it’s stripped of language, status and familiar social roles. I drew, read and reflected a great deal and at one point I even considered abandoning my identity entirely and trying to rebuild myself. This thought eventually faded into the background. Learning to stay present with myself, rather than erase myself, became a decisive turning point.

A significant part of this transformation is taking place in my shared studio, where I work with three Danish artists. Although my Danish is still limited, we communicate in English. Working closely with them has helped me understand how closed and conservative Danish society can be in many ways and at the same time how curious and deeply empathetic it is, especially towards other cultures. I learn a lot simply by listening to what concerns them, how they work and which topics matter to them. This daily coexistence has strengthened my practice and helped me become bolder in expressing my own opinions.

I feel this especially within Copenhagen’s international community, where many people carry their own experiences of migration. My work often resonates most strongly with those who have lived through similar processes and these encounters — at my exhibitions, studios and festivals — have become an important confirmation for me. Copenhagen hasn’t made my journey easy, but with its rhythm, its people and its communities, it has given me the space to ask fundamental questions about belonging, responsibility and coexistence. This life experience has profoundly reshaped my artistic voice, making it louder and more attentive.

Anastasiia Lodde | More And Less

Anastasiia Lodde | More And Less

Many of your works balance humor, absurdity, and quiet tragedy. How important is irony or surreal exaggeration in helping you speak about trauma and loss?

Irony and absurdity matter to me, but not as tools of ridicule or distance. I don’t try to mock anyone, or to speak from above or below. I see myself as an observer — someone who passes experience through herself, like through a lens — and communicates what she feels.

My first work with fish appeared in 2023, when I was still processing my initial sensations after relocation. It depicted a fish riding a bicycle through an underground city, a metaphor born from a very physical experience. I imagined a freshwater fish suddenly finding itself in a cold, salty sea: the density of the water changes, movement becomes heavier and slower and everything requires more effort. At the same time, this slowness allows the fish to look around, to notice the world and to begin questioning who it is within it.

This is where absurdity enters my work, as a way to describe something that is difficult to articulate directly. Later images, such as a fish sitting at sunset and eating fish soup, grow from the same place. Nothing dramatic happens, yet the tension is already present. I try to show that trauma and loss often exist in everyday routines, contradictions and repetitions. For me, humour is a form of care. I am a pacifist and irony is neither a weapon nor a shield; it is a way to remain human. In this sense, the absurd feels closer to me than realism, because it reflects the uneven and non-linear work of memory.

Your art often critiques systems that manipulate and divide, while emphasizing humaneness and resilience. Do you see your practice as a form of quiet resistance?

Yes, but not in a confrontational way. I see my practice as a form of resistance rooted in attention and care — in a refusal to simplify human experience.

Once, a woman came to my exhibition and shared her story. She had emigrated more than 25 years ago and told me that, in order to feel at home, she felt she had “to cut off her roots”. This phrase deeply affected me and raised a question I couldn’t let go of: why should belonging require erasing yourself?

This encounter led to the work More&Lees. In it, a fish stands in the middle of the sea, surrounded by a forest and a sunset. In one hand, it holds a phone; in the other, a cable, hesitating whether to cut it or not. This moment of stillness is essential to me. The fish does not act — not because there is a right answer, but because the choice itself deserves to be seen.

My work is about creating space for doubt, memory and individual decisions. I believe immigration is not about forgetting who you are, but about holding complexity: carrying your roots while continuing to build something new.

Anastasiia Lodde | Underwater | 2024

Anastasiia Lodde | Underwater | 2024

Many of your figures appear isolated yet interconnected within shared spaces. How do relationships – family, community, society – influence your compositions?

Of course, all of this influences my work. Even though I have a strong and supportive community here, including an international one, I feel a growing distance from my family, who remain elsewhere. This distance is difficult to articulate fully; it exists more as a feeling.

Elements of home are therefore always present in my work. They appear as matchboxes, telephones, dishes, or gingerbread on the table. These are not nostalgic reconstructions, but small possibilities to return briefly to a time and a place that no longer exist in reality.

Community, on the other hand, shapes how my figures coexist. They often share space without fully merging, remaining close yet separate. This reflects how relationships can feel in an international environment — built on care, but also on distance and difference.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.