Stella-Maris Onwuama

Where do you live: USA

Your education: Bachelor’s degree in Biochemistry and a Master’s degree in Biotechnology; continued artistic development through independent study, exhibitions, and professional work across multiple countries.

Describe your art in three words: Labor-intensive, intimate, intentional; quiet, emotional, exacting

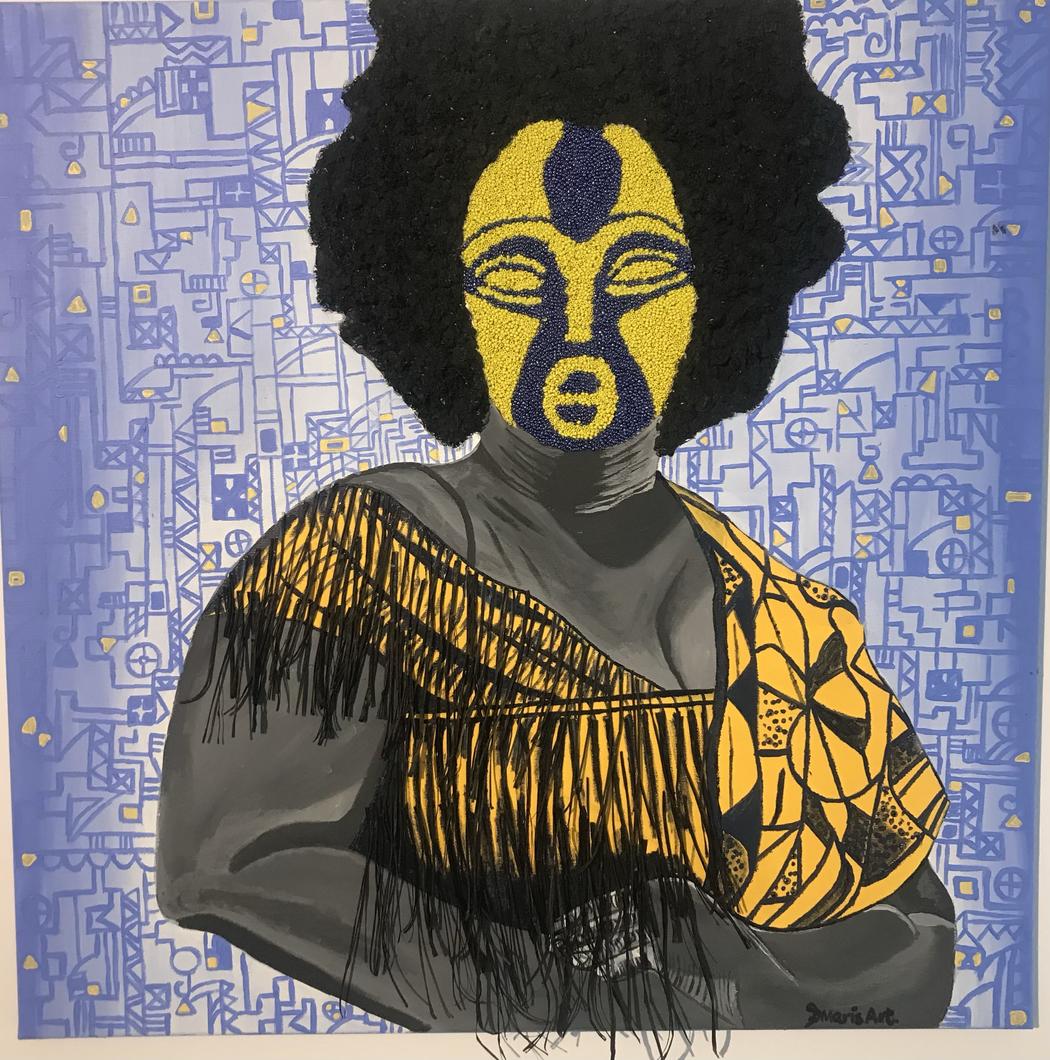

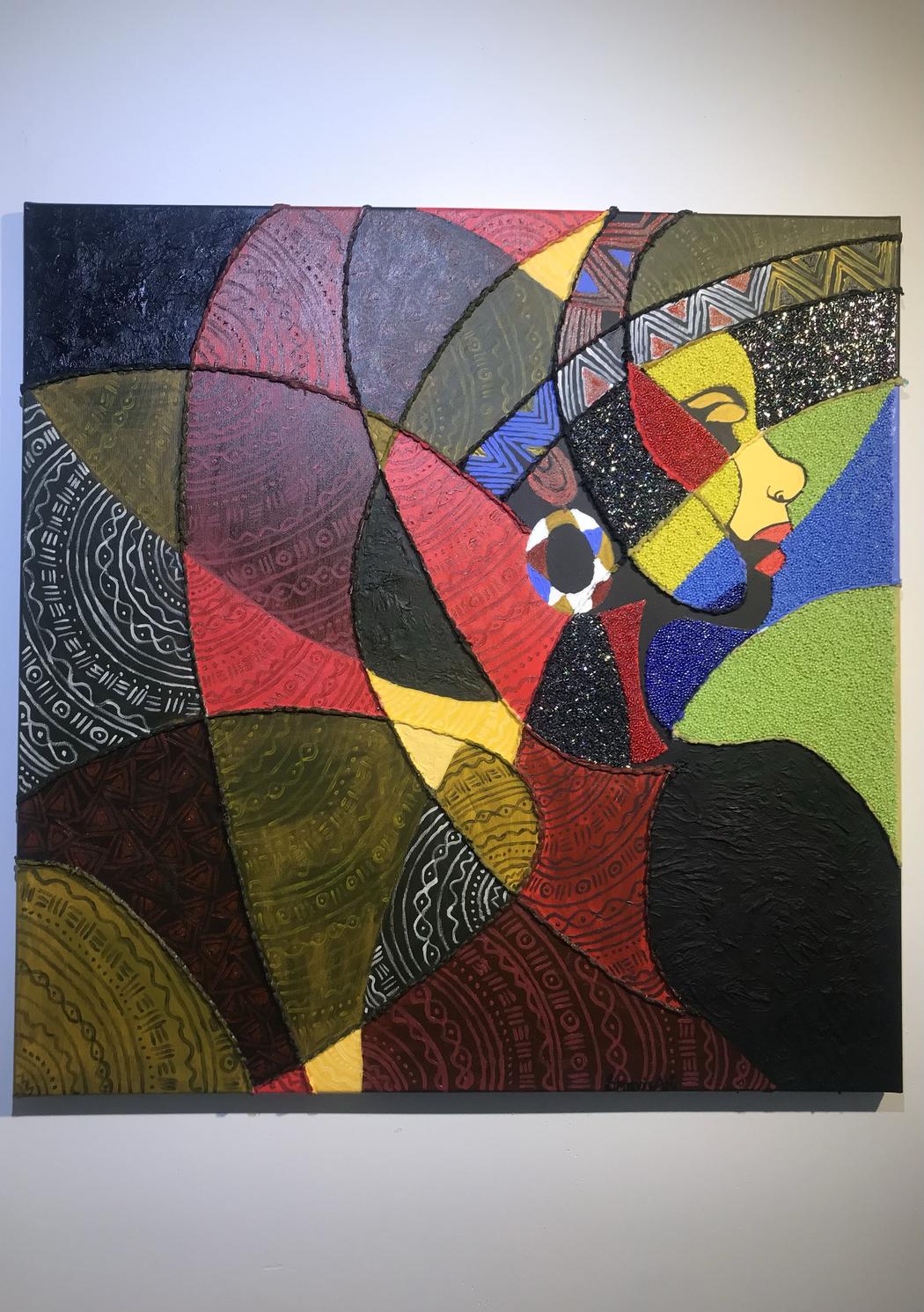

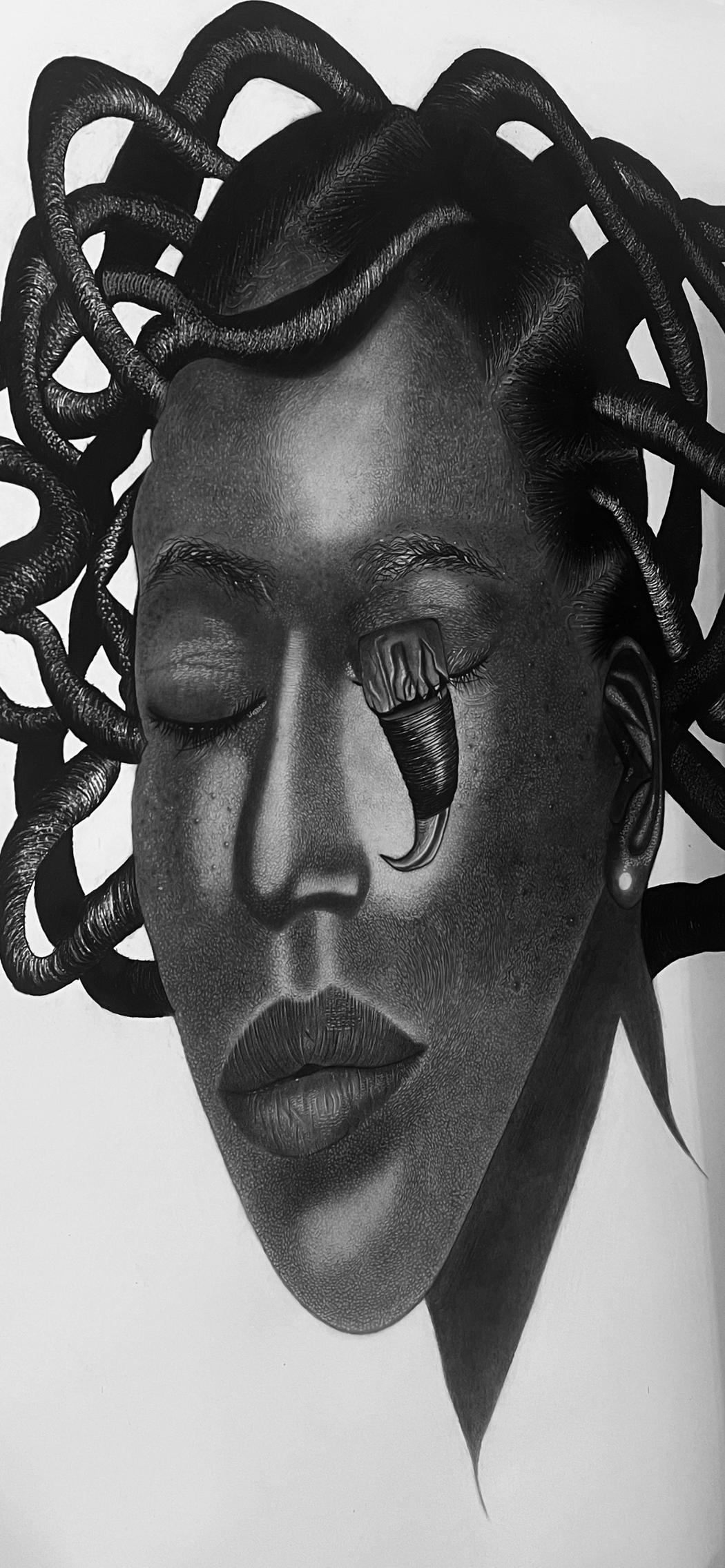

Your discipline: Visual artist working primarily in hyper realistic portraiture and bead-based mixed media

Your work moves between hyperrealistic portraiture and bead-based art. What initially drew you to these two very different yet complementary mediums?

I was drawn to both mediums because they demand presence and patience. Hyperrealistic portraiture taught me how to truly see, to slow down and honor a face beyond surface likeness. Beadwork came later, but it felt intuitive. Each bead is tiny, intentional, and cumulative, much like a single mark or cell. Care is what binds them together.

What connects them is care. Whether I am drawing a face or placing thousands of beads, I am engaging in a quiet, repetitive act that resists haste. One medium focuses on accurately capturing the human image, while the other uses accumulation to create meaning. Together, they allow me to explore visibility on how people, stories, and labor are seen or overlooked.

You often speak about slowness, repetition, and precision as acts of care and witnessing. How does the physical process of making influence the emotional meaning of your work?

The physical process is inseparable from the emotional meaning. Slowness allows me to stay with difficult emotions without rushing past them. Repetition becomes a form of meditation, a way of holding space for memory, grief, or resilience.

Precision, for me, is an ethical choice. It is a way of saying that this person, this story, this moment deserves attention. Coming from a life where instability and loss forced me to grow up early, making art slowly is a refusal of disposability. The labor embedded in the work mirrors the emotional labor behind it.

Your portraits emphasize dignity and quiet emotional presence. What do you look for in a face or a gesture before deciding it deserves to become a portrait?

I am drawn to moments of stillness when someone is not performing, not posing, but simply present. A subtle tension in the eyes, the weight of a gaze, or a calm that carries history.

I am not interested in drama or perfection. I search for humanity. It’s a face that frequently makes me think of people who are rarely in control and who secretly possess strength. A gesture is worth retaining if it is emotionally honest and encourages reflection rather than spectacle.

Beadwork plays a central conceptual role in your practice. How did you first begin working with beads, and what symbolic meaning do they hold for you today?

I began working with beads during a period when my life required extreme patience and endurance. Beads felt honest, they are small, repetitive, and time-consuming, much like survival itself.

Today, beads stand for accumulation and the way that little deeds of kindness, perseverance, and hard work become something enduring. Additionally, they make attention to previously underappreciated crafts, ornamentation, and femininity-related customs. I’m recovering the gravity of beadwork and respecting the labor that goes into it by bringing it into conceptual and fine art environments.

You transform materials often dismissed as “decorative” into central artistic elements. What challenges or reactions have you encountered from audiences or institutions because of this?

There’s often an initial hesitation and some viewers are unsure how to read the work because beads don’t fit neatly into traditional hierarchies of fine art. But that discomfort is part of the work.

Once audiences understand the time, precision, and intention behind the material, their perception shifts. I have found that institutions and viewers are increasingly open to rethinking what counts as serious material. I have learned to trust the work to speak for itself and to remain steadfast in my artistic convictions thanks to this challenge.

Your life experiences – loss, financial instability, and early responsibility – deeply inform your work. How do you balance personal vulnerability with artistic intention?

I don’t see vulnerability as exposure for its own sake. I am intentional about what I share and how it is translated visually. The work isn’t a diary, it’s a transformation.

I use structure, discipline, and craft to hold difficult experiences with care. That balance allows the work to remain accessible without becoming overwhelming. My goal is not to ask for sympathy, but to create connections and spaces where viewers can recognize their own resilience reflected back at them.

You work across the United States and Europe. How have different cultural contexts shaped the way your work is perceived or created?

Working across different cultural contexts has taught me how meaning shifts without losing its core. In Europe, there is often a strong focus on materiality and tradition, which deepens conversations around craft and labor. In the U.S., audiences tend to engage more directly with the emotional and narrative aspects of the work.

These differences have made me more intentional and flexible as an artist. They’ve shown me that while the language of art changes, themes like dignity, care, and visibility are universally understood.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.