Clémence BROLL

Where do you live: Bordeaux, France

Your education: Performing Arts / Dancer-Performer and Choreographer

Describe your art in three words: Universal · Pure · Innovative

Your discipline: Visual Arts and Dance

Your artistic practice connects movement, gesture, and visual expression. How does your background in performance and dance influence your way of painting?

Painting, for me, is also a physical experience of the world. In both painting and dance, it’s about bringing a story to life, shaping a distinctive gaze in relation to others, and taking the viewer on a journey where the path matters as much as the destination.

I’ve learned to think of the work from both inside and outside — within the interweaving of lived experience, sensitivity, and visibility — to seek certain perspectives, a particular way of capturing movement and vitality. However, I’m not sure what influences my composition most; the different practices respond to, contaminate, and generate one another. The subjects I explore resonate with each other, carrying shared constants. None of these mediums are sealed off. They function together, as a system — each one informing the other, each bearing the memory and discoveries of the others.

You describe your process as an “intuitive and embodied exploration.” Could you tell us about the moment when intuition takes over — how do you recognize it?

It’s both a terrifying and exhilarating moment; it arises when my consciousness steps back, and my hand seems to move ahead of my thoughts, in a suspension of control that I do not try to regain, trusting the somatic intelligence built from experiences, readings, and gestures repeated and accumulated to the point of automatism. I listen to what is seeking to be born. Sometimes, I mix pigments at night like a sleepwalker, not knowing how daylight will reveal them; and from the unpredictable, something surprising and unexpected often emerges.

Thus, I never manage to follow a sketch in the strict sense. An initial idea is born, accompanied by a constellation of autonomous elements and a perception of what might come; but it is only through painting that all the pieces of the puzzle begin to converse, to organize, to find their own coherence. The work assembles itself, guided by an internal logic that sometimes escapes me.

I accept getting lost, again and again, with a strange faith that the path will reveal itself by walking.

Clémence BROLL | Spirale | 2022

Clémence BROLL | Spirale | 2022

Many of your works seem to capture transformation — movement becoming form, gesture becoming image. What role does metamorphosis play in your art?

It’s something that already happens to me in the process itself. For instance, I begin to paint in a state of vital urgency, as an act of survival — a way to contain and/or transform what would otherwise overwhelm me, to magnify it until it produces an outcome. I am often surprised by what emerges; art cannot remain silent, and the work sometimes acts as a mirror that does not reflect the image I believe I’m projecting, but the one I unconsciously carry. Words come only afterward, awkwardly, in an attempt to grasp what has taken place.

So painting means crossing through — moving from one state to another, from one form to another, from one consciousness to another. This dynamic animates my work. I would like to experiment with special-effect inks that change depending on light, humidity, temperature, or even time itself. I like the idea — and accept it — that the artwork has its own life, that it continues to evolve beyond my presence, recognizing impermanence as a fundamental condition of reality.

Clémence BROLL | Respire | 2025

Clémence BROLL | Respire | 2025

The textures and colors in your paintings evoke a strong emotional resonance. Do you begin with a specific emotion, or do the feelings emerge as you create?

Neither one nor the other — or rather, both at once. There is always an emotional atmosphere, an affective tone that passes through me as I enter the act of creation, and it probably imbues the final work. But my emotions transform as I lose myself in the process. The act of creating alters them, deepens them, and fortunately overturns them completely. So it is neither an absolute starting point nor a pure end result.

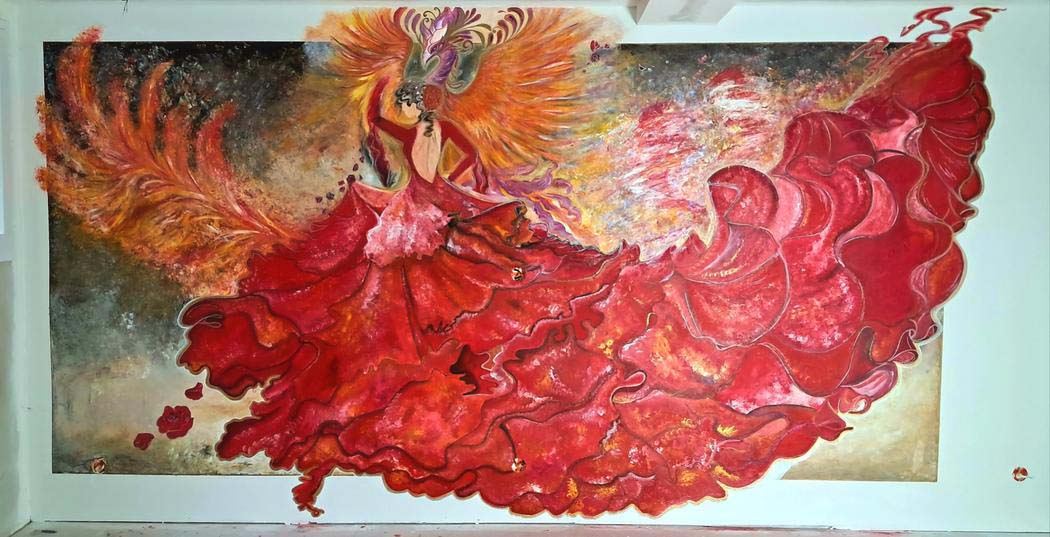

Clémence BROLL | Renaissance | 2025

Clémence BROLL | Renaissance | 2025

You mention working outside academic frameworks — how has this freedom shaped your personal techniques and aesthetic identity?

This choice to evolve outside academic structures has never meant ignoring the rules. Above all, it was a necessity — a way to experiment with my own methods, to move forward through trial and intuition, to learn by unlearning. Working this way has its limits as much as its virtues, but discovering “by chance” opens me to a vital sense of wonder that keeps my curiosity, my rigor, and my constant desire to surpass myself alive.

This freedom has also allowed me to naturally blend disciplines, to permit myself every kind of experiment and detour, and to develop an aesthetic identity that academicism might have smoothed out. Perhaps this hybridity — inherited from my upbringing and background — is precisely what I’ve been most criticized for, resulting in a graphic language that is varied, unfixed, and regularly renewed, driven by recurring obsessions.

My work may seem raw at first, because it emerges from a direct dialogue between my obsessions and the material itself (for example, I often paint with my fingers); but also because it embraces the presence of the accident, of the deliberately slipped “error,” and of the shift — with the intent to unsettle the gaze by subtly displacing what, within the established order, seems out of place. Beneath its apparent simplicity and its “Unicorns,” my compositions rest on precise, schematic internal logics within a network of interrelations.

I am aware of the political reading that underlies any artwork — including and especially my own — but I refuse to turn it into a marketing product, even though working outside institutions means consciously or not rejecting a certain system of validation and legitimization in art. It is to affirm that one can be an artist without having been knighted by artistic institutions — whether academic or recodified by conventional contemporary spaces.

The history of art has always been built through movements, each with the charm of telling the world — sometimes in opposition to its era, sometimes in harmony with its technical and intellectual advances. Today, contemporary art seems to have become an acquired stance, sometimes flirting dangerously with new forms of obligation, often ethnocentric.

Beyond how the art world is administered, I now move along a dual path: seeking spaces for dialogue and encounter while asserting my own approach with its demands — an approach that, in turn, must provoke the same desire for exchange and dialogue. No artist can build themselves outside the world, nor outside their own history. It is essential to remain in constant dialogue with other practices, other approaches, other spaces and temporalities, so as never to freeze one’s thought. For instance, among my upcoming projects is a mural that converses with the work of Rivera, as well as a series of paintings inspired by artists such as Degas, who explored the concept of movement.

Clémence BROLL | Et…Elle Se Changeait En Papillon | 2025

Clémence BROLL | Et…Elle Se Changeait En Papillon | 2025

Your images often seem both cosmic and deeply human — do you perceive a connection between the inner world and the outer world in your practice?

Everything that happens in the great universe resonates in my small universe, and vice versa. Behind this seemingly vast universe lies the reality and complexity of the world — its violence as much as its brilliance; and I build filters that make it bearable to look at, that allow one to endure the unbearable, to transform chaos into a form that can be contemplated, to transmute the overflow of both internal and external reality into something livable.

At the other pole, my small universe is itself infinite — made up of traces, fragments, encounters, and experiences that accumulate and sometimes require, in the very moment, to be translated, expressed, given the possibility to appear to the world, to give form to this inner richness that would otherwise remain unarticulated and unspeakable.

One can recognize a dreamlike and metaphorical aspect in my paintings and drawings, since they often arise from a meditative state or a dream (a process of meditative and Jungian-style analytical work), but also from internal representations. They also draw on myths, tales, ancient knowledge, and ancestral oral traditions — which themselves are ways of bearing witness to the world.

They are nourished by a cultural heritage of elsewhere — by other ways of inhabiting the world, by travel and encounters with others in a “differing” and deferential dialogue. These multiple influences create hybridizations, interweavings of forms and symbols that speak of a multimodal belonging to the world.

These paintings are the fruit of an act — both ritual and social, sensitive and spiritual, poetic and psychic — that is shared. They create a space where all these dimensions can coexist and respond to one another.

Clémence BROLL | Psyché | 2021

Clémence BROLL | Psyché | 2021

Many of your paintings seem to celebrate feminine energy and vitality. How do you approach the representation of the body and movement?

The feminine is not a subject I intentionally seek to address. I am aware of the historical issues, the power dynamics that shape our society, and how women are affected by them—as well as the current upheavals in art history that are being reexamined through these struggles.

By the very nature of my being in the world, I cannot escape being a woman. From this I derive a kind of fighting capital, a management of possibilities and limitations, and a sense of solidarity—beyond my own circumstances—with all those who find themselves in situations of domination.

The feminine presence in my work draws from the flow of “mythological” influences inherited from the cultures I have encountered (Latin America, Eastern Europe, Indigenous, Asian, and Oriental traditions). These figures are plural, irreducible to the sacrificial or guilty posture that monotheistic religions can convey under the guise of beauty. In certain animist cultures, for example, naming a forest creature does not even imply a gender assignment.

The body is, objectively, the expression of power relations. It is a site where polarities coexist—tenderness and strength, gentleness and authority, grace and power, determination and courage, etc.—without the need to assign these qualities to one gender or another.

This ambivalence is present both in the mythical figures of the sacred feminine and in the women of my lineage, who carry within them this nobility—a heritage that perhaps influences my gaze in representation. Yet these same traits can also be found in the figures one might describe as “masculine” in my work—though you might read them as androgynous, beyond binary assignments, touching upon a kind of universality of the body-as-power.

In my work, movement is not perceived in an abstract way but functions like an oral signal. It is less about freezing its form than about preserving the trace of a living, experienced, sensitive body—a body that leaves its remnants in space, its echoes, its afterimages. A body that is still here but already elsewhere, inscribed in continuity.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.