KOMIYA (Julia Kovalchuk)

Your art blends traditional Asian techniques with modern interpretation. What draws you to this fusion?

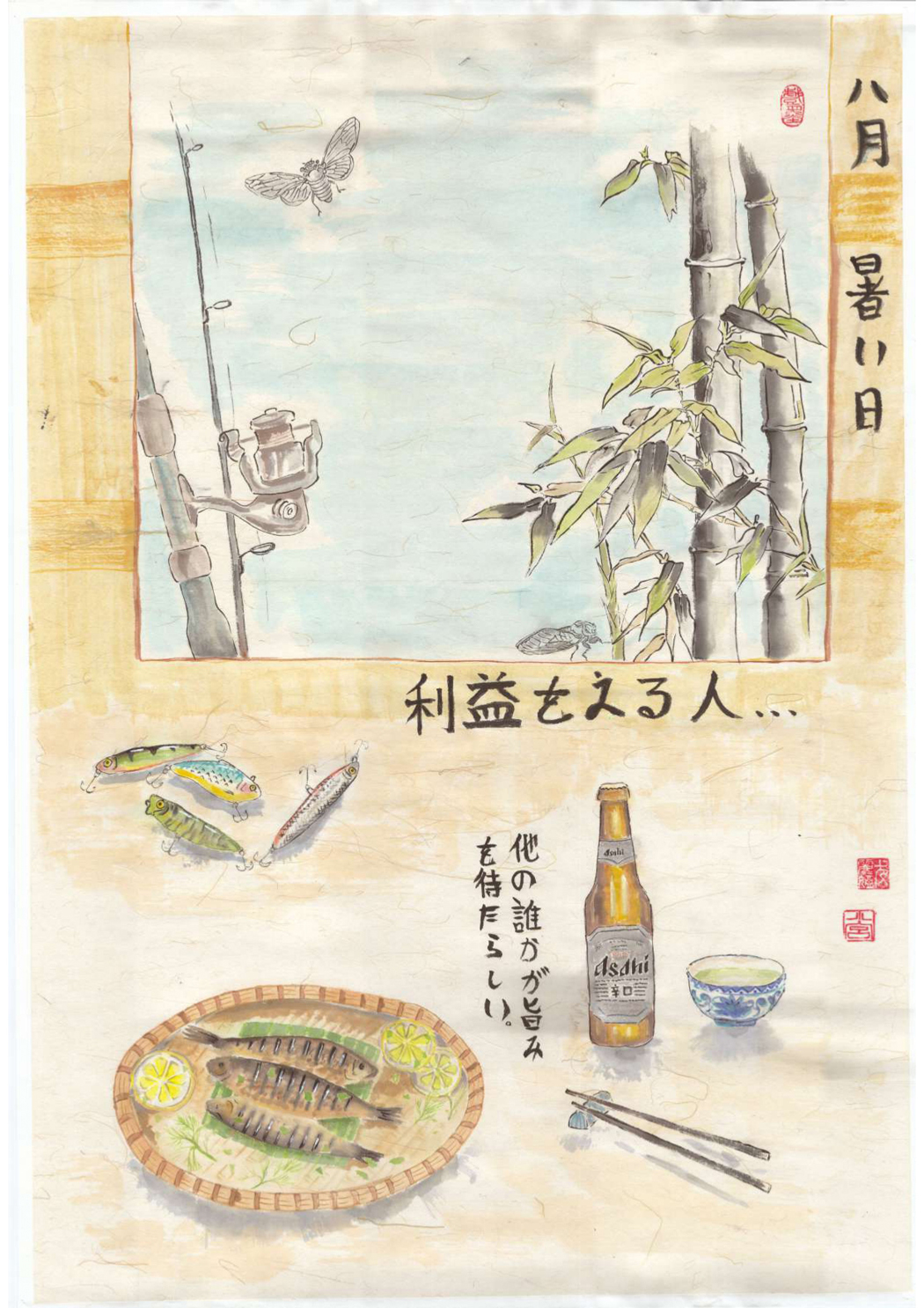

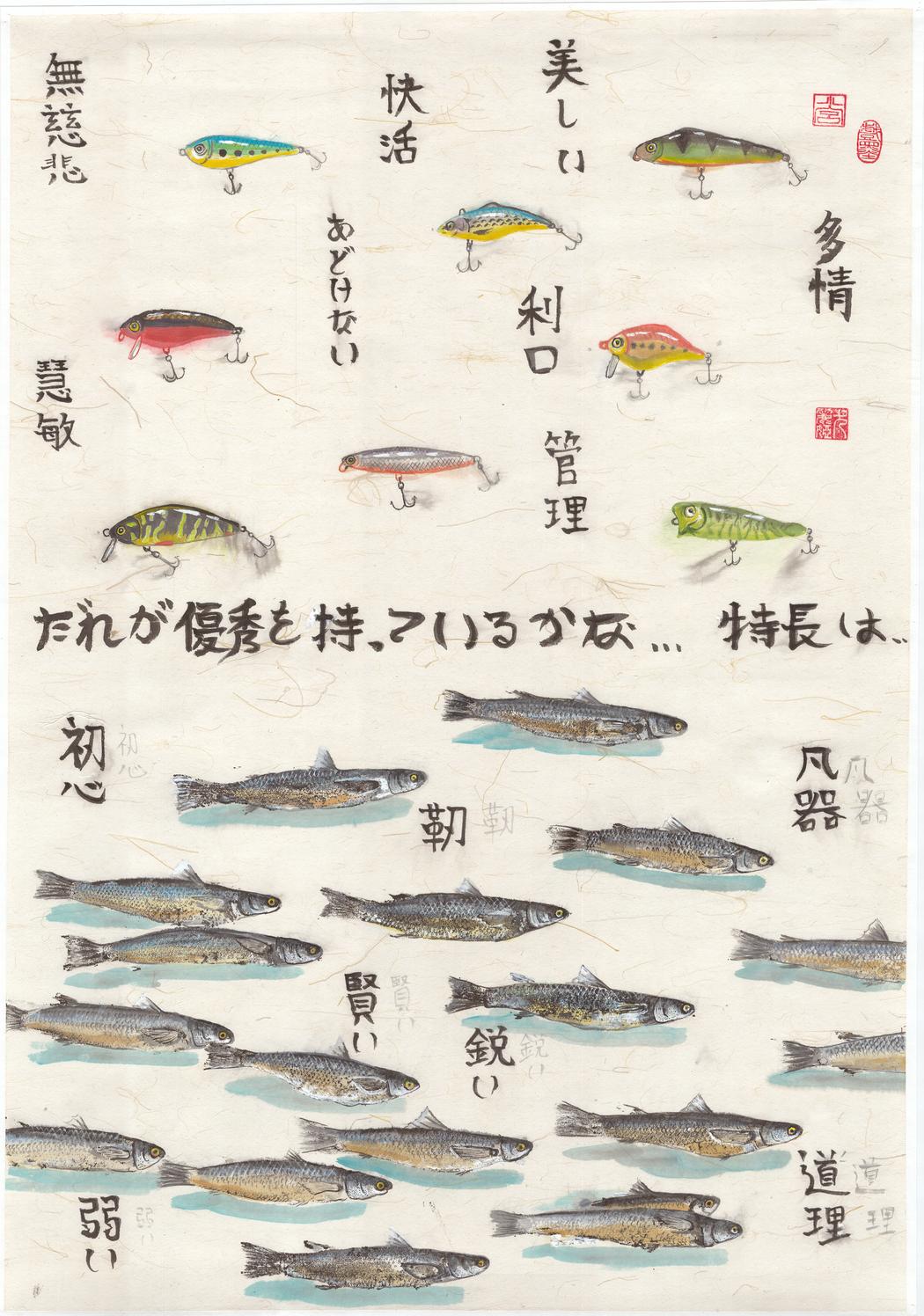

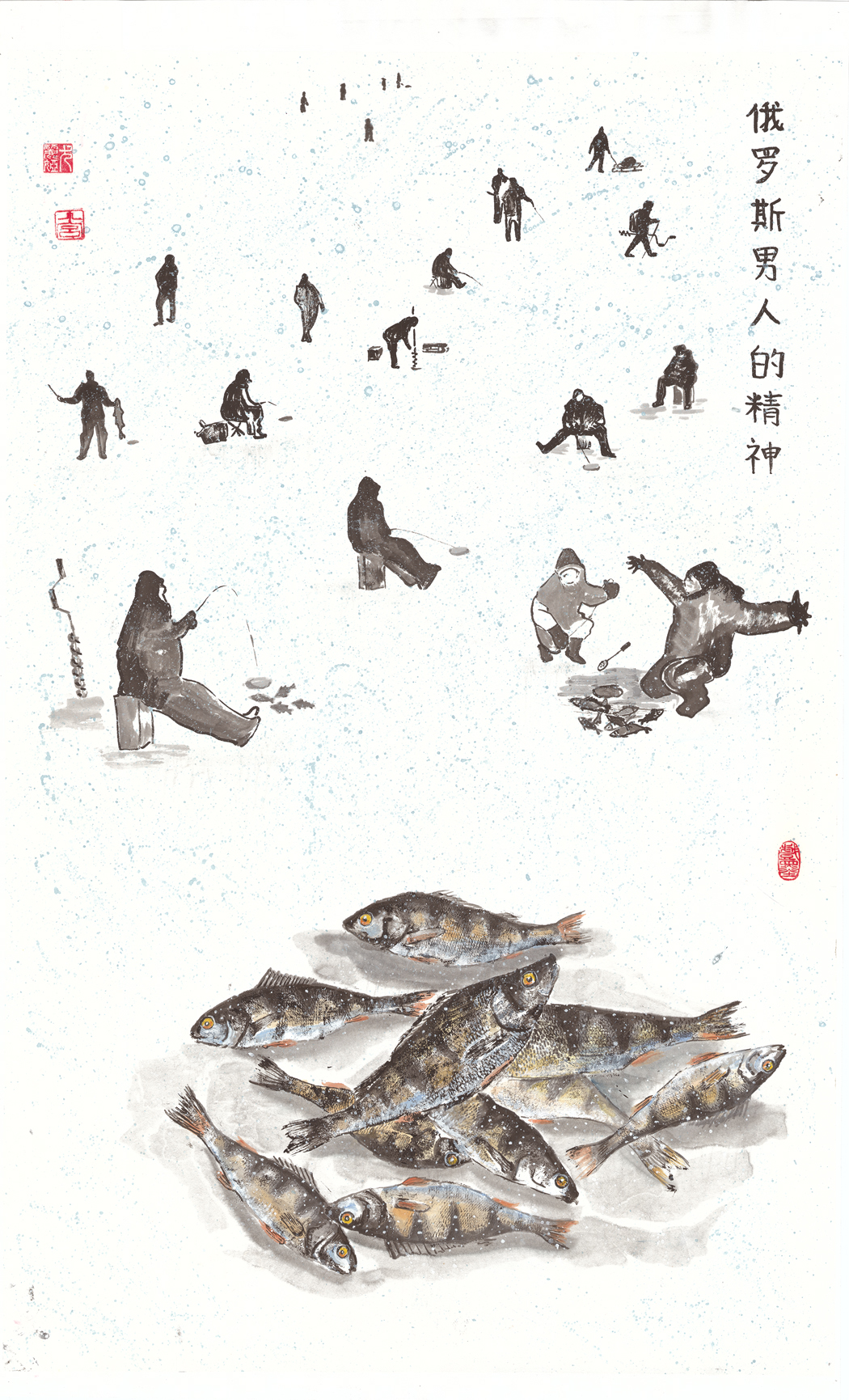

It all started with discovering Chinese painting techniques when I attended a master class at a gallery. Then I went back again and again. Suddenly, I realized that all the complex drawing concepts I had developed during my youth in art school were not necessary. Everything could be expressed with a single line, a swift brushstroke—concise yet vibrant. Gradually, I became more immersed in it and spent several years painting landscapes, still lifes, fish, and birds, copying Chinese masters and creating my own compositions.

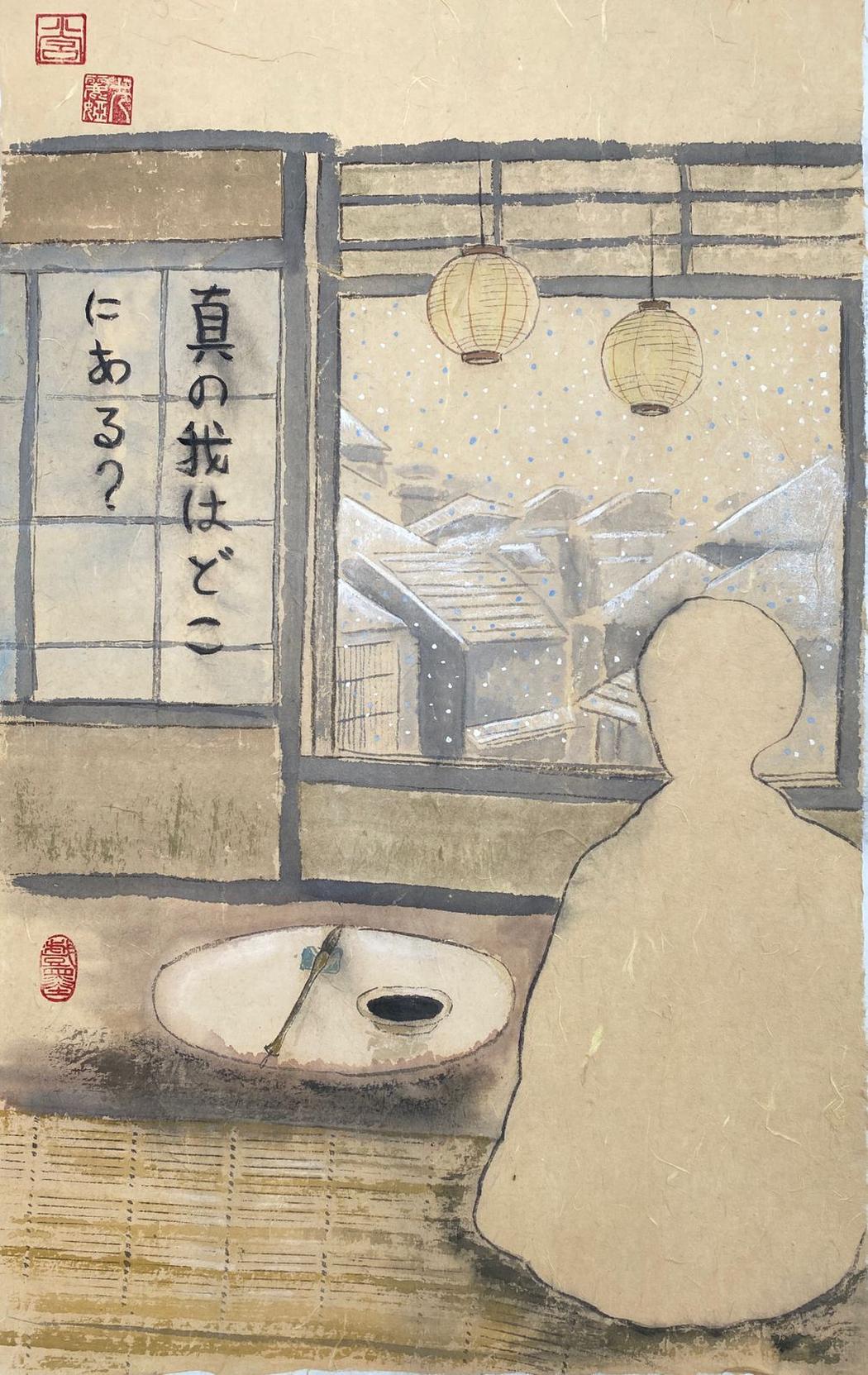

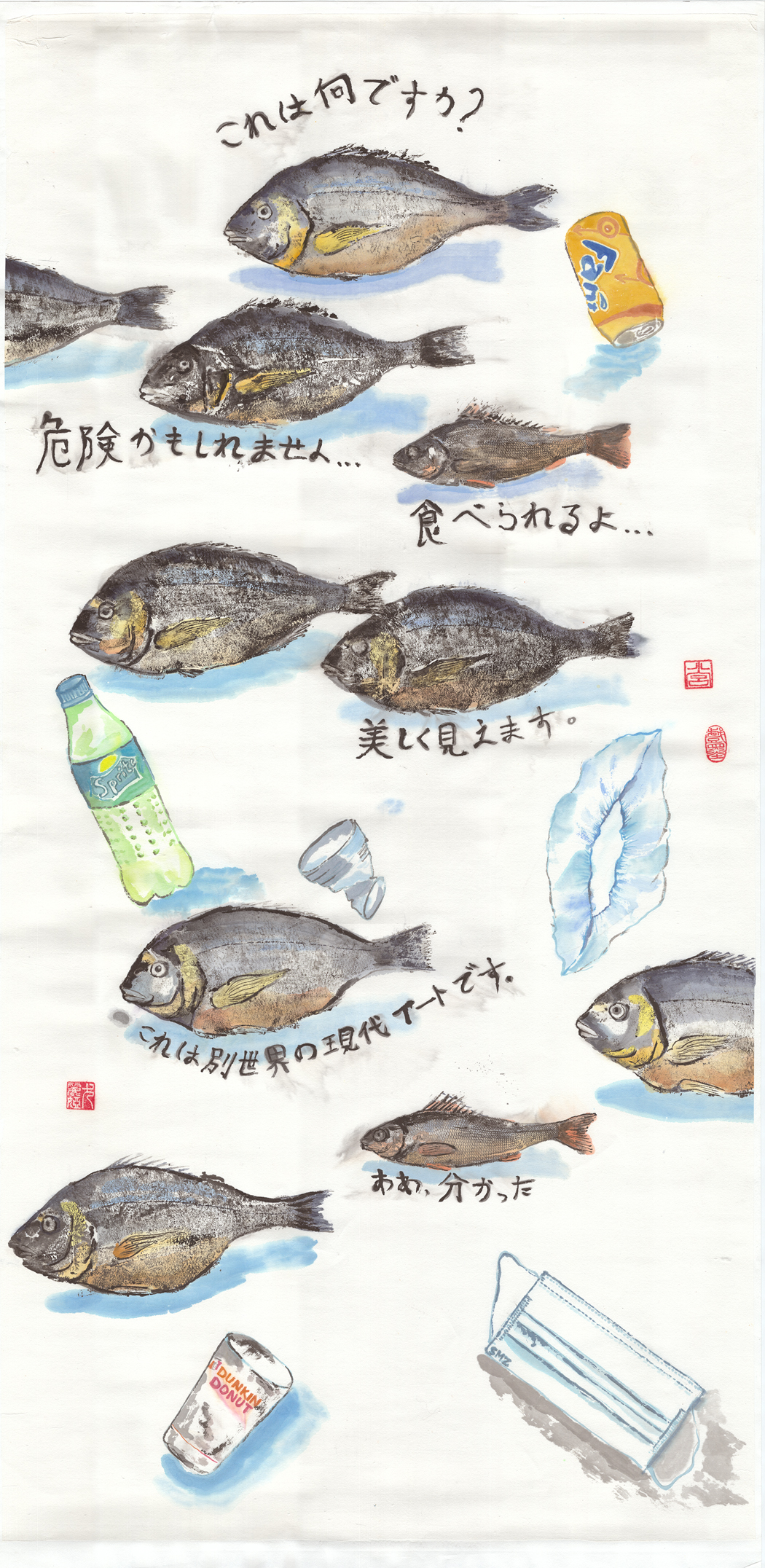

After a while, I realized that I had developed my own expressions. I grew fond of certain techniques, such as gyotaku and suminagashi. The metaphorical language became a tool, allowing me to make statements indirectly, without being forceful. The beauty of allegories and metaphors, both in the image and in the textual (hieroglyphic) message, became multidimensional and captivating to me. Since I had spent several decades studying Asian cultures, this aesthetic became dominant in my art. This led to the combination of what we see in my paintings, which has now become my personal brand.

KOMIYA (Julia Kovalchuk) | Diptych

KOMIYA (Julia Kovalchuk) | Diptych

What does nature mean to you as an artist?

Nature is life, and we are part of this planetary life, and only pride makes us think otherwise. In modern society, it is common to separate humans from nature, which justifies a barbaric attitude toward the environment and blinds us to this pain. In my work, I do not want this separation between humans and nature. I hope that one day I will achieve such unity in my worldview, both as a human and as an artist.

KOMIYA (Julia Kovalchuk) | Diptych

KOMIYA (Julia Kovalchuk) | Diptych

You often combine images with text. How do you choose what to write?

What to write? – this is a question I rarely ask myself. The thought and message resonate initially, but I spend a lot of time reflecting on how exactly to write it. I carefully select the phrase, sometimes writing many phrases in different sizes and matching them with the painting. Everything matters – the choice of words, style, and language. In Japanese, the same phrase can be written in many ways, depending on the style and meaning that best suits the painting and reveals its essence. The statement and the image are equally important and fully support, complement, and reveal each other, or at least, I want to believe so.

How has your background in East Asian studies and ethnography influenced your visual language?

Ethnography, religion, and the East have always fascinated me. When I say always, I mean since my childhood, from the earliest memories I have. This interest has guided me for almost half a century now, and I believe it won’t fade away. The stars wrote it into my destiny. Since this is my deep subconscious interest, it naturally manifests in my paintings. Born on an island in the Pacific Ocean, I consider myself a part of the region. I notice that I share many of the cultural codes of East Asian countries; I feel them, and they genuinely interest me, especially their aesthetics.

In addition to the East, I spent a long time studying Russian ethnography, particularly the imagery of sacred geometry on the carriers of traditional material culture. However, in Russia, this tradition has disappeared, leaving only shadows, while in India, it is alive. Since both Russia and India share the same archetypal geometric patterns, I often turn to materials on Indian ethnography, such as the tradition of drawing kolams, among many other things.

Do you consider your works to carry a philosophical or spiritual message?

My works are a continuation of the internal philosophical and psychological dilemmas that life presents to me. And since that is the case, they cannot be anything else. This is my practice of presence: the gaze is directed at the familiar, but slightly shifted, as if searching for something hidden and finding it, or imagining it. It is difficult to assess objectively because we live in a half-imagined, constructed reality.

The composition grows from an imprint, a print, a trace, an interaction with the material. I try to avoid heaviness in my works, choosing pastel shades and lightness, striving for transparency, allowing the work to “manifest” rather than being assembled by will. The composition is not constructed but rather dispersed in space, where each detail arises on its own— as a result of contact with the material, not my intention.

The prints of leaves, flowers, and fish are not decorative forms but independent participants in the artistic statement. They carry the living breath of the moment, its trace, its vibration. For me, color is an emotion that arises in the moment, while gray is the base, the neutral fabric of reality.

Instead of final statements, I strive to leave an open space for the perception and personal conclusions of the viewer, inviting them to be surprised, sharing a discovery, and in a way asking — Do you feel this too? I hope I am not the only one who sees this, and I want to share my sense of enjoyment of the moment, of discovery, of beauty, with someone else.

I often use diptychs — because, like everyone else, I think in binary oppositions. But sometimes I really want to go beyond them, and I strive for a holistic perception of the world, where boundaries fade, and everything becomes part of a single movement.

What role does calligraphy play in your creative process?

I’m certainly not a calligrapher. I write like a child, but I don’t aim to be skilled in calligraphy. I graduated with a degree in Japanese studies from university, and then I lived in Japan for a while as an exchange PhD student. I don’t claim to be proficient in calligraphy or to have perfect knowledge of the language, but I deeply love both. What’s important to me is expressing an idea with a phrase that most concisely conveys my thoughts, and the painting is just an illustration of that phrase. It’s the phrase, its contemplation, that I spend a lot of time on—sometimes much longer than I spend painting the artwork itself. Sometimes the image in the painting is so expressive that the text becomes unnecessary, and in those cases, I intentionally avoid it. Even though it’s not written, the text is still present, if you look closely at the work.

You use mineral pigments, ink, and gold foil. What attracts you to these materials?

Black ink can be as deep as the blackness of the night sky, or as light as a delicate wisp of smoke, yet it’s the same material. It’s like a person. Pigments are sometimes essential to evoke a person’s feelings and emotions, to color a painting with mood. Gold leaf is important. The golden color has always been widely used in Asian aesthetics, and it’s indispensable. It seems to give the painting a different dimension.

I also feel admiration and respect for the rice paper, washi. Sometimes it seems to me almost self-sufficient, so beautiful! It is my unconditional companion. I want to explore the possibilities of paper more deeply, the variety of its texture, inclusions, fibers, and colors. For each piece, I carefully choose the paper, and I have a favorite store in Beijing where I specifically go to buy it.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.