Weixi Kuang and Junpeng Liang

Junpeng Liang

Where do you live: London

Your education: The master is currently studying at Bartlett School of Architecture, UCL

Weixi Kuang

Where do you live: London

Your education: The master is currently studying at Central Saint Martins, UAL

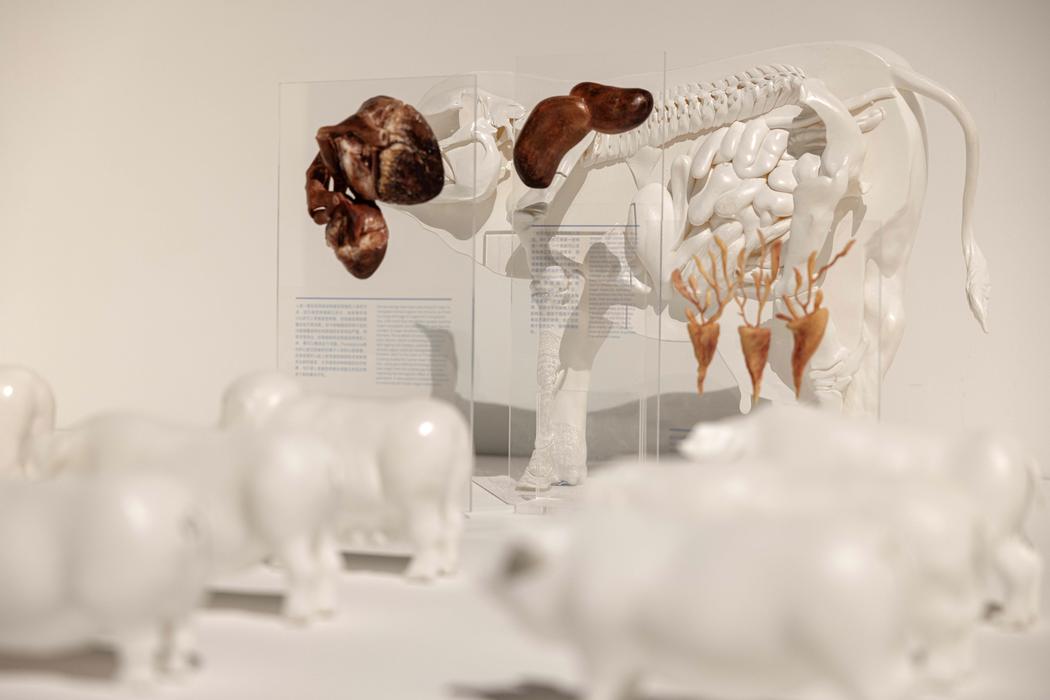

Weixi Kuang and Junpeng Liang | 展览图

Weixi Kuang and Junpeng Liang | 展览图

Your work spans biodesign, algorithmic aesthetics, and critical design. How did your collaborative practice begin, and how do you approach interdisciplinary creation together?

Our collaborative practice began with a shared curiosity about how emerging technologies—especially in biology and computation—reshape the way we define life, identity, and nature. We met while studying in an environment that encouraged crossing disciplinary boundaries, and quickly discovered overlapping concerns in biodesign, algorithmic logic, and speculative thinking.

Rather than dividing labor by skill, we approach creation as a continuous dialogue. Each project begins with a research-driven question—something that sits between science and society, between what is known and what is imagined. From there, we explore across scales and systems: from cellular processes to social rituals, from biological data to visual simulations.

Our work often unfolds in iterative loops between disciplines: one of us might experiment with form or code, while the other translates lab insights into tangible narratives. We are not aiming to “solve” problems, but to make hidden tensions visible—to design spaces where uncertainty, doubt, and possibility can coexist. It’s this back-and-forth between critique and creation that defines how we work together.

What role does ecological ethics play in shaping your conceptual and material choices?

Ecological ethics is something that quietly but persistently shapes the way we think and create. It’s not just about choosing the “right” material or reducing impact—it’s more about asking the uncomfortable questions. What systems are we part of? What assumptions are we reproducing without realizing it?

When we start a project, we often look at how biological, technological, and cultural systems intersect. That naturally brings up questions about responsibility—especially when working with living or synthetic materials. We try to stay aware of how even small choices—visual language, framing, fabrication—can carry ethical weight.

Instead of aiming to be “sustainable” in the conventional sense, we’re more interested in exploring the messy spaces where ecology, innovation, and uncertainty meet. Sometimes that means exposing contradictions or showing things that feel a bit unsettling. For us, ecological ethics isn’t a checklist—it’s a way of staying awake while navigating complexity.

In your view, how can art reshape human–nonhuman relationships in the age of the Anthropocene?

We think art has a unique way of making abstract relationships feel immediate and emotional—especially when it comes to how humans relate to the nonhuman world. In the age of the Anthropocene, where our actions reshape ecosystems on a planetary scale, it’s easy to either feel overwhelmed or detached. Art can interrupt that distance.

Through speculative design, sensory experience, and narrative, art can help us imagine what it means to live with rather than above other species and systems. It can create space for empathy with things we don’t usually consider—like bacteria, soil, synthetic organisms, or even future ecosystems.

We’re especially interested in using art to slow things down: to build moments of attention, discomfort, or curiosity that shift how we perceive the more-than-human world. Not to romanticize nature, but to recognize how entangled we already are—and maybe become a little more responsible because of it.

Can you walk us through the process of creating works from human microbial communities? What were some unexpected discoveries?

Our work with human microbial communities started with a question that’s both scientific and existential: If our bodies are constantly shaped by microbial exchanges, then where does the “self” actually begin and end?

In our early research, we were fascinated by how the human microbiome isn’t fixed—it’s something we inherit, but also something we acquire, shape, and share throughout life. Microbiologists describe two major sources of microbial inheritance: one from the mother—through birth, skin, gut, and womb—and one from the social and environmental world we grow up in. Some researchers even refer to this maternal microbial transfer as a “second genetic system.”

That was a striking idea for us. It suggested that who we are biologically is not just encoded in our DNA, but also carried through invisible layers of shared life—bacteria, fungi, microbes that travel between us constantly. We’re not as separate as we think. Eating together, touching, talking—these are all acts of microbial exchange. Our bodies are porous. Our boundaries are blurred.

This inspired us to think of the microbiome almost as a medium: invisible, dynamic, intimate. We began working with microbial data, swabs, and simulations—thinking not only about how these organisms live in us, but how they write us. The challenge was to translate that into something people could feel or confront physically.

Weixi Kuang and Junpeng Liang | 作品拍摄图

Weixi Kuang and Junpeng Liang | 作品拍摄图

How do you see the ethical implications of giving inorganic matter “life” through microbial design?

We see microbial design not as a way of “giving” life to inorganic matter, but as a way of questioning what life even means—and who gets to define it.

When microbes animate a surface, change its color, digest or react to the environment, it blurs the boundary between what we typically call “alive” and “non-living.” That threshold—between inert material and biological activity—is not just scientific; it’s deeply philosophical and ethical.

There’s something quietly powerful about watching something seemingly lifeless begin to respond. It invites reflection on control, authorship, and responsibility. Are we creating new forms of life, or are we just rearranging existing ones? If something grows, evolves, or even decays—does that make it “alive”? And what happens when we design for that ambiguity?

The Enso Series speculates about non-existent bacterial worlds. What drew you to work with lignin and white rot fungi?

We were drawn to lignin and white rot fungi because they sit at a strange intersection—between decay and regeneration, biology and technology, past and future. Lignin is one of the most abundant organic polymers on Earth, yet it’s largely seen as waste in industrial processes. White rot fungi are among the few organisms capable of breaking it down, and in doing so, they quietly shape the chemical history of forests.

From a speculative design perspective, we saw white rot not just as a decomposer, but as a creative agent— something that reorganizes matter and redefines boundaries between lifeforms. We were especially interested in how its tubular hyphae structure mirrors algorithmic logic: it branches, loops, redirects, and adapts. That formal and functional elegance made it the perfect collaborator in imagining a postanthropocentric material future.

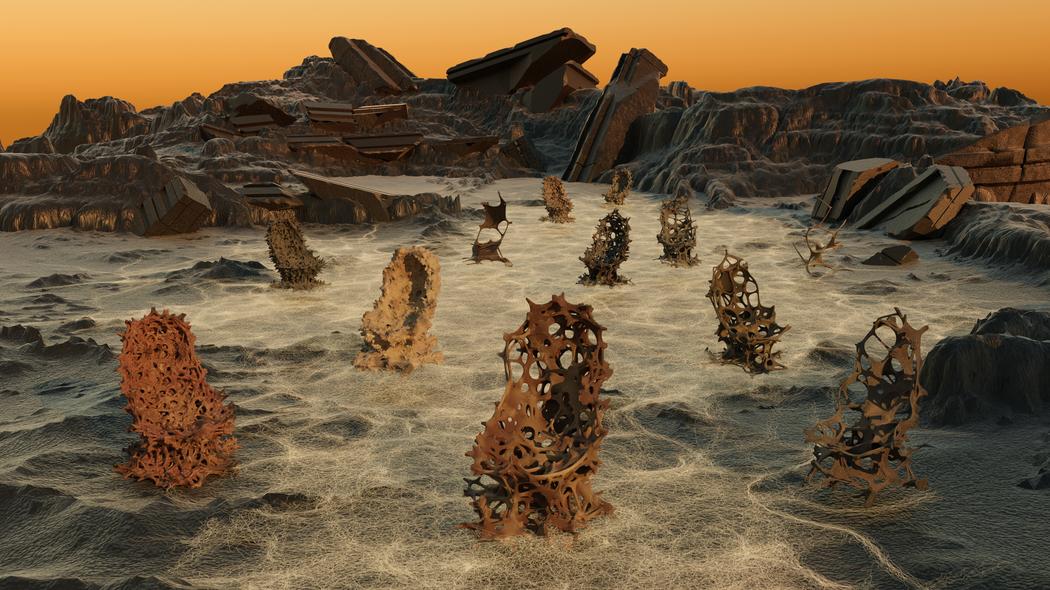

Weixi Kuang and Junpeng Liang | 圆相椅子墓园

Weixi Kuang and Junpeng Liang | 圆相椅子墓园

Can you elaborate on how the multiverse theory informed the aesthetics and concept of this series?

The multiverse theory gave us a language to think beyond a single dominant narrative of reality. If every lifeform operates within its own version of the world—its own perception, logic, time—then reality is already plural. This idea resonated deeply with fungal consciousness: fungi don’t experience time or communication the way humans do, yet they play foundational roles in the ecosystems we rely on.

In Enso, we used the circle not just as a visual motif, but as a symbol of cyclic, non-human time—fungal time. We imagined each chair in the series as a kind of “world”—a fragment of an alternate timeline where microbial processes are primary, not peripheral. The forms evolved algorithmically, drawing from the radial and cross-sectional structures of decaying wood, generating speculative architectures for a future that centers fungal intelligence.

How do you balance scientific rigor with speculative storytelling in such works?

For us, science and speculation don’t compete—they feed each other. We begin with research: biological papers, microscopy, lab experiments, field studies. But we don’t stop at explanation. Instead, we ask what that data feels like, or what kind of narrative world it might open up.

We’re careful not to use scientific concepts purely as metaphors. We treat the biology seriously—white rot’s enzymatic logic, lignin’s material properties—but we stretch its implications. We see storytelling as a way to explore ethical, ecological, and ontological questions that science alone might not ask. In that sense, speculation is not a departure from rigor—it’s an extension of it, into the poetic and the possible.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.