Bia de Sousa Costa

Year of birth: 2001.

Where do you live: London, UK.

Your education: BA Fine Art: Drawing (graduating in June 2025).

Describe your art in three words: Social, historical, community.

Your discipline: Multidisciplinary.

Instagram

Your work focuses on social activism and the role of female artists throughout history. Can you talk about how these themes influence your practice and the choices you make as an artist?

Well, I don’t think we ever stop being citizens while doing our jobs. We might not always be active citizens when we choose not to bring this voice into other duties and responsibilities of our lives – some constraints and hardships can defy our morals. For example, I can’t expect a single mother on a low salary to go on strike for a few days, knowing that money is going to decide who gets dinner between her children. This is unfair, but I think the fundamental learning is to educate people on their rights and secure better living conditions for current and next generations, aside from the direct accountability asked to those who neglect them. Again, to influence that woman, mother and breadwinner to go on strike means to have the right collective support that reimburses her in other ways. This conflict happens in rhetoric discourses for artists, too. Without close relationships to introduce them to art spaces and funding, there is a tendency to limit how to represent their work. Thus, navigating the art industry will define how we want to be represented, and so, I am interested in analysing the female art-making experience and how history has been portraying their accomplishments. As an artist, gaining influence and influencing my local environment is what I aim to be part of. Creating larger spaces for female artists to collaborate, connect and bring a community in – new possibilities for integrating female art makers and collectives.

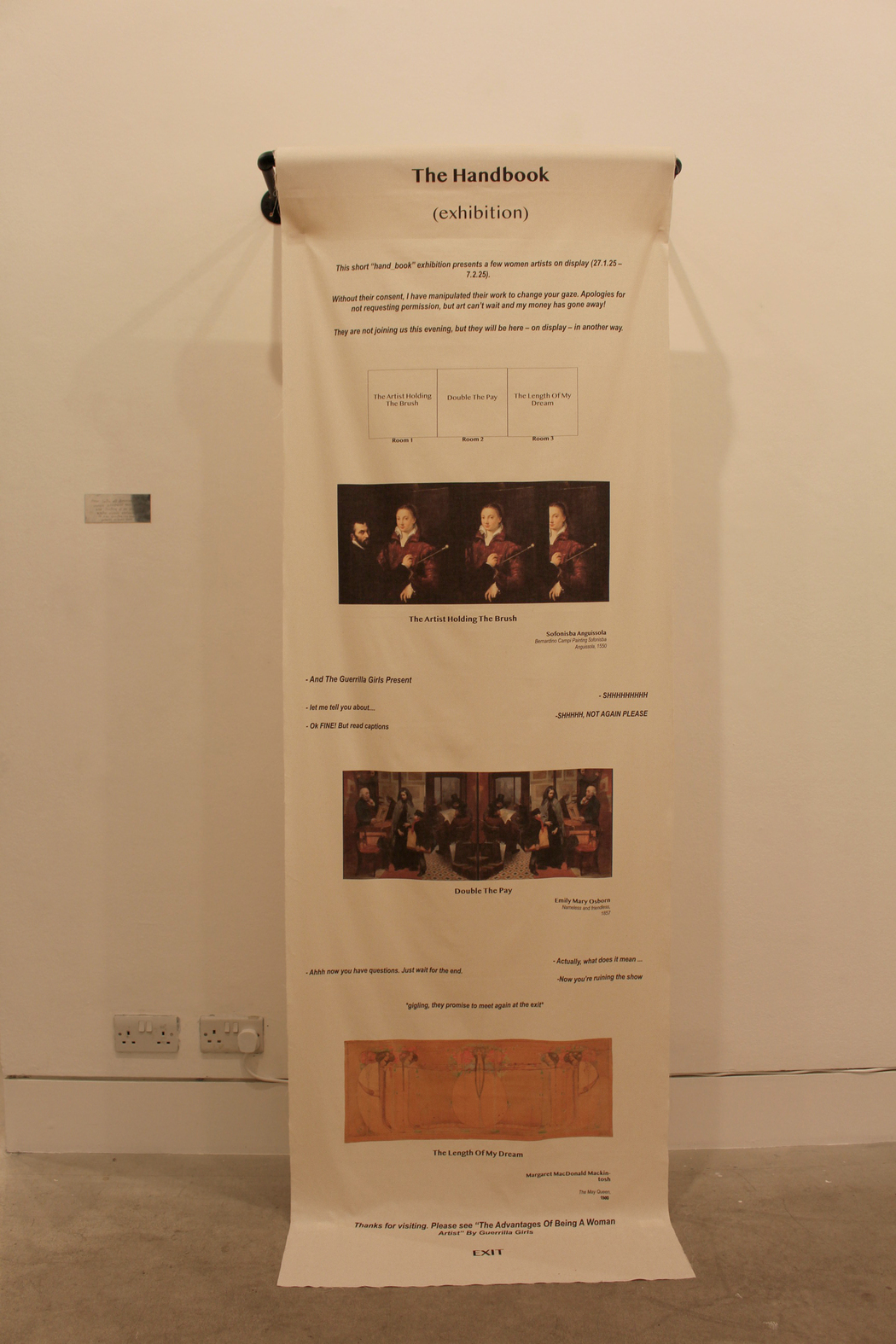

In your project ‘The Handbook,’ you explore the historical representation of women in art. How do you approach the balance between history and contemporary artistic expression?

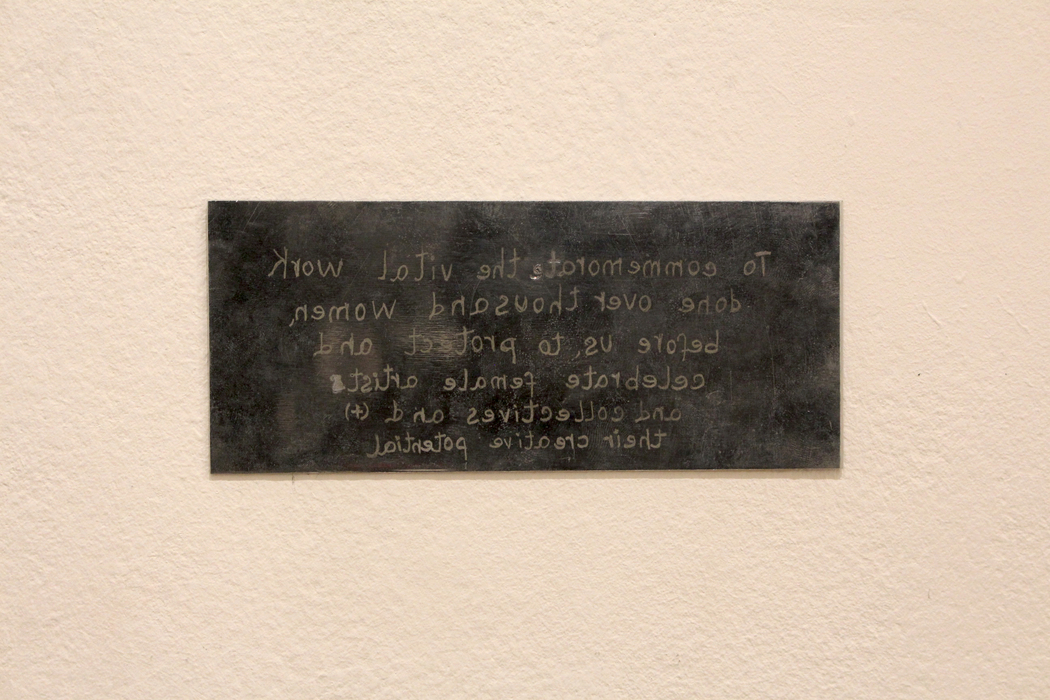

Manipulation is my favourite process. I like to believe that we are more often persuaded by something lacking rigidity, which doesn’t impose behaving in a certain way. The Handbook is about appropriating paintings of pivotal women artists as a bait to uncover paradigms that keep on happening nowadays for female artists. This old conversation we first read in books, watch in films and then feel in our skin, on being the muse vs. the artist or the lack of equal pay for females. Despite still feeling bothered by these generational operations, at some point, I think I have to laugh at all this. When you enjoy the joke, you don’t assimilate the shame, but you do look at the display with new eyes – this is how I want my audience to engage. When allowing on-site learning and the use of memory, the public will have a bittersweet, enjoyable and unexpected experience. Consequently, this strategy in facilitating interactions balances contemporary artistic expressions with subtle tricks to retake power in directing and honouring the history presented.

You mention that your work is often shaped by your surroundings and through research. How do you choose which aspects of history or society to address in your work?

It is very easy for me as I start working with my intuition as a guide to grasp the tiny details that I am interested in a scene or story. If you are like me, you always want to know more about the beginning of the unknown, which comes to you through spontaneous suggestions. For example, I don’t own a car, but I live and work in the same area, so I walk a lot. This way, I have time to look around and observe the day passing by and the movement or sounds I can hear. It feels like listening to a radio station, except that I cannot move channels, and yet, I can spot the wally in every situation. My immediate surroundings allow me to reflect on the state of the world while evaluating my connection to the community. They spill my unsettled answers about issues I care about, whereas my research is a hunt for an explanation about these situations I witness. As we have extensive access to different forms of literary arguments, it is also important to separate the line between them and general opinions, especially online. Overall, I let the work be an exchange of evidence (research) and critique (impressions) of the topic chosen, but never a final agreement on how it must be seen in my work.

Can you describe the process behind your current video installation and the immersive experience you’re creating for the audience? What emotions or thoughts do you want to evoke through this work?

The current video installation that I’m working on follows the body as a performance in a specific site and routine. In this context, the notion of time breaks as the character is seen stuck in that role. I think this is quite an interesting point to use when producing a ten-minute film and encouraging visitors to stay until the end. How do I make it interesting enough so they can lean on the emotions and thoughts that I evoke? Post-production is my answer. I am such a fan of odd and experimental films that keep the audience guessing about what is happening and what will come next. In some ways, the process behind it reflects The Handbook in the voices entering the space like strangers, without a linear script. As in previous works, I am challenging myself, but now, ironically, I am more judgmental about my body’s capacity to express this visual language. Since the original plan for the installation has changed due to lack of space and later brief adjustments, I am currently adjusting the work’s installation. After all, this constraint gives me options on how to create multiple versions for immersive experience within the same work. However, my non-negotiable is that I’m looking to offer an intimate connection through the voice heard, while the audience keeps a scrutinising eye on the person performing.

As a multidisciplinary artist, you use both sculptures and video installations in your work. How do you decide which medium to use for specific concepts or themes?

Since I have worked with different mediums before, now, I tend to choose based on the best result for the concept I want to explore. I like making quick sketches to understand the space/time it takes and then being clear about the non-negotiable aspects I can’t afford to lose. Can the theme still shine under new restrictions? For me, the concept can always evolve but not to the point of sacrificing the theme. Recently, I found a love for materials, which makes me navigate budgets in such an exciting way. So, I am putting money first into printing pieces, and the rest is about using cheaper / recyclable materials for the structural aspects of my work.

How has your experience with the educational institutions, like UAL, influenced your art? Do you feel your relationship with the studio and institution has impacted your artistic journey?

Another aspect I can’t dissociate, as an artist now, is my relationship with UAL. Currently, I’m on my fifth year in this institution as a student (including occasional paid work), and I constantly reflect on the changes in my practice. Before enrolling at UAL, I had no formal arts education and here, I opened my eyes as a maker instead of an art historian. It is called fine art: drawing and little relation has to traditional drawing. Instead, it tries to emulate drawing as an architecture of ideas, but I have a hard time explaining exactly what we do. At least, we are being trained to become artists, aligned with our work and knowing how best to articulate it. This year, I’ve had the best resources available so far, with consistent artists’ lectures, more drawing workshops and tutors in the studios. However, UAL is spread throughout the city, across six different campuses, which makes it hard to push boundaries for the things that students need. As often said, big institutions confine lots of people to a few members making decisions. The studio space can sometimes feel tight for everyone and I would wish to have more of that trial-and-error studio research during the holidays, when it is closed.

In your statement, you discuss the impact of female artists in art and society. How do you think contemporary art can contribute to changing the societal views on gender and art?

I’m very careful when using the word ‘gender’ as I don’t think it carries much respect for all of us. In my opinion, it separates lines about the quality of work as it classifies an artist’s success based on gender. Nevertheless, there’s a need for amplifying female artists as a community, based on a long journey of artists/collectives over thousands of generations. I think contemporary art can feel, sometimes, very distant and impersonal when it highlights the form without speaking much about the subject/history of the object. Perhaps it is less subjective to question the artist’s identity behind it, but without contextualising the process, the artwork won’t have a deeper representation on further references. Also, I think contemporary art is an ambivalent concept and makes the audience question it. As artists, we frequently spend a lot of time designing, writing and creating structures that can facilitate discussions about the shape of our lives. So, how is the state of our lives seen by those who consume contemporary art? I don’t know; I’m biased here since I also produce work in this field. Still, what matters is how others feel about female artists showcasing interdisciplinary layers of attachment with a designated site, preferring experimental and ‘sterile’ encounters (contemporary art). Overall, it reframes how these artists take space and use collective voices, which impact societal views within communities through education for young girls living in post-exhibition worlds. Ultimately, I hope it shapes cultural spaces, accessibility and bigger dreams.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.