Joshua Kennington

Year of birth: 2000

Where do you live: I’m an emerging artist based out of Toronto, Ontario, Canada

Your education: I’m

currently studying my undergraduate at OCAD University (Ontario College of Art and

Design University)

Describe your art in three words: texture , motion , layers

Your discipline: multi-disciplinary

Website | Instagram

Your work focuses on memory, nostalgia, and fleeting moments. What initially drew you to these themes, and how do you approach them in your art?

Ever since I began producing art, specifically with my photography practice, I’ve considered the value of memory, and how photographs become these sort of elements of nostalgia as time moves on. They become symbols of moments, fleeting from the present, forever lost in the past, but still close to us in terms of what they mean to us as memories, reminders we were there when that image was taken. I’ve always appreciated that sentimentality of the image, and how one cherishes it through their life. I kept in mind this notion of memory and sentiment when producing my paintings, perhaps not in a totally representational approach, as to recreate a memory, but perhaps say, in using more gradual colour tones, or trying to simplify my imagery so as to emulate how memory by its very nature won’t necessarily capture every detail in a specific time and place.

Can you elaborate on how your local environment and subconscious influence your abstract landscapes and dreamscapes?

My artistic practice is informed in part by my experiences of exploring and running about the river valleys near my home since childhood. I’ve always appreciated nature and seeing different landscapes and ecosystems. I’ve volunteered for a few local organizations over the years, managing ecosystems in the Credit and Don River Valleys in the Greater Toronto Area. At the same time, I’ve always been a city kid, used to taking subways to get around the city, and the bustling, busy roads of my local neighbourhood. I choose to represent elements of both of these environments in my work, in part to recreate them as memories of their own and to celebrate the mundanity of them.

My practice is influenced as well by dreams, specifically the idea of the dream as an alternate, warped, but sometimes almost life-like representation of our own lives at times. Up until the pandemic, I used to have rather odd dreams that stuck with me, to the point where I almost had a fear of dreaming in my sleep in high school. When I first began to paint, I wanted to represent these mixed emotions I had, but also try to think of dreams as what could be, and sort of this point of imagined reality.

In spite of my background in photography, I don’t desire representational painting, partly because I find there’s something so telling about looking at a painting which doesn’t leave every detail open to the viewer. I think in some ways, looking into one’s dreams is to see something inside them, something you wouldn’t see on a surface level.

You describe your work as a synthesis of natural and man-made forms. Could you share an example of a piece where this synthesis is most evident?

Much of my work generally skews toward one type of form, but one of my oil paintings, called Terminus Oppidum (which is Latin (roughly) for Frontier Town), captures both identities well. It’s an abstracted representation of the street I live on, as it passes through my local river valley, with allusions to a city in the distance. It was an experimental work for me, with many light layers of paint used to create perspective and a convincing field of view. At first glance, the repeating forms of trees are apparent as they flank an illuminated yellow road, which rises as it exits the valley. A swirling confluence of clouds pours from the top of the valley, filling the sky in smoky greys.

Man-made intervention into this landscape is most prominent from the yellow road, but a distant skyline of repeated yellow lines floats in the sky to the left, behind the clouds but very prominent nonetheless. I used tape in this work to emulate a sense of large, man-made constructions that were nearby, perhaps, behind the curtain of clouds. In that sense, this work feels rather light, and to me, a bit theatrical.

Your background in photography informs your focus on light and composition. How do these photographic principles translate into your paintings?

Ever since I began drawing, I’ve kept a few aspects of photography to heart. These translated over to my paintings, even though I mainly draw representationally and paint in abstract form. Perhaps the single most important element to me is composition and how every object and form in my paintings relate to each other. I’ve come to really value giving form space to breathe, whether it’s the smallest line of paint on a canvas to represent part of an object or even to provide enough space for a diptych to comfortably be situated in a space. I always try to consider different viewpoints in my work.

I generally follow the rule of thirds in my work, but I’m more open to pushing this principle as hard as it is for me. The other principle I constantly yearn to achieve in my work is a convincing sense of lighting or luminance. I used to practice this by never painting with white paint, using the black canvas of my painting as the original light source to illuminate my scenes as I choose. I still maintain this technique but use white in some of my works if necessary.

I’ve also come to appreciate different color tones through photography, which have informed my color palette in my paintings, like different gray tones, yellows, and blues.

Impressionist painting and abstract symbolism are central to your practice. Which artists or movements have had the biggest impact on your work?

When I first began painting, I felt lost and unsure of where to start, until I began looking into surrealist painters, like Yves Tanguy and Max Ernst, and Impressionists like Monet. I resonated with the colour schemes used by these artists, and as I began to do more research and practice painting, I moved toward a more deliberate, methodical system of blending paint. In the last few years, I’ve found inspiration through Romanticist J. M. W. Turner, and to a lesser extent, the work of Mark Rothko and Philip Guston. I think semiotics and different signs we identify with in painting can be so important in shaping how we see work. It’s these associations which can either resonate with a viewer or remind them of another work or idea explored in another, which I find so interesting.

This idea of connecting to an audience, creating meaning through one’s work by ensuring some sense of meaning is instilled within it, fascinates me. It’s obviously not possible as everyone’s perception of a work is different and informed by their own experiences, but I still believe the power of symbolism in painting is something remarkable and often irreproducible in any other medium.

You often use sculptural techniques to ground your work. Could you explain this process and its significance in conveying your ideas?

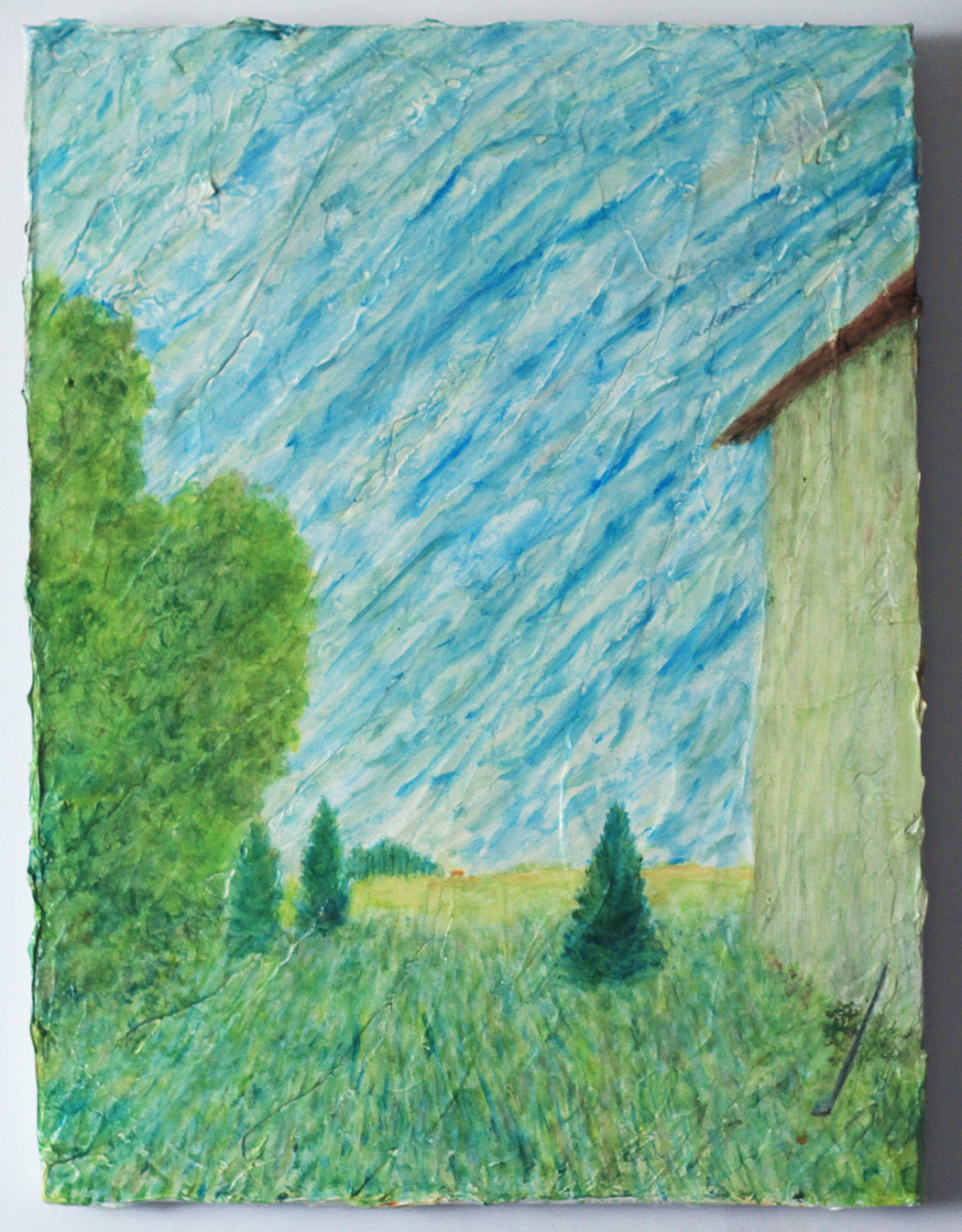

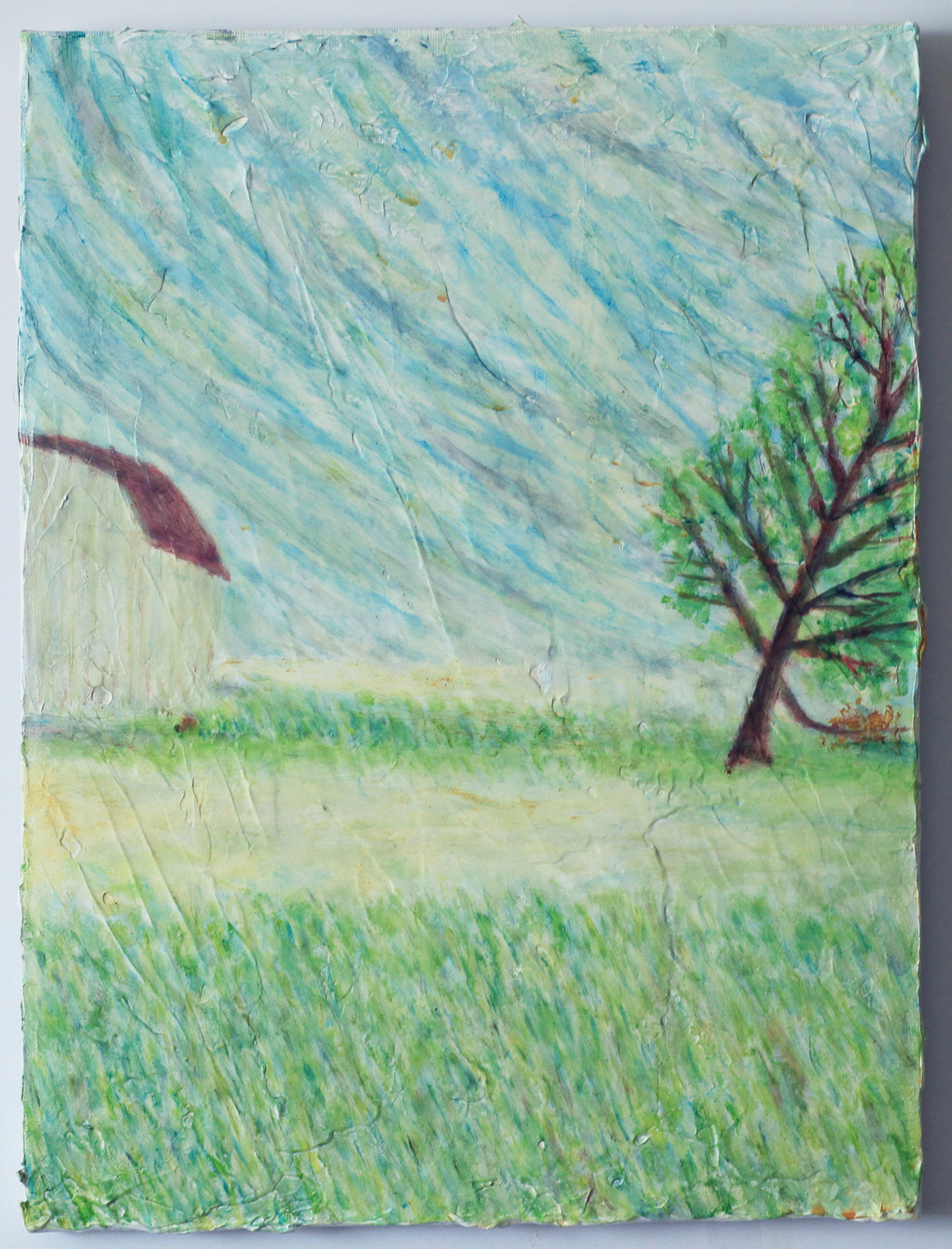

Before I begin any painting, I apply heavy body gesso to my work, whether my canvas already has a layer of pre-applied gesso or not. I usually apply several layers to give my work some depth and use this kind of gesso because I want my work to have grooves and ridges that influence the final outcome. This process was born out of an accident: one day, I’d forgotten to smooth over my base layer before painting, but I found the resulting texture interesting, and it gave the work new meaning in my eyes.

I began experimenting with the idea of leaving out a step in my grounding process and, over time, started using more layers and eventually a denser type of gesso in my paintings, applying it with a palette knife to smooth over my base layer. As I paint over this base layer, the ridges shift to a degree, but they also influence my brush strokes and lines depending on where and how I’m painting. These paintings begin to resemble maps, almost as if I’m painting routes over rolling hills and mountain ranges to get from one side of the canvas to the other.

These grooves, bumps, and intrusions from a flat, pictorial plane act as a symbol of perception and the memory of the landscape or abstracted reality I’m creating. It’s almost as if one had a photograph of, say, a farm, but they were seeing it through the perspective of the original owner of that farm, with each ridge and groove representing their lived experience and perception that shifted their understanding of the work.

To me, then, these textures act like the rosy-colored lens of nostalgia, looking back to a dreamscape or landscape—not quite seeing the composition as it truly is, but still grasping the essence of that time and place.

What advice would you give to emerging artists interested in exploring similar themes of memory and the ephemeral?

Given how universal these themes are, I suggest to anyone interested in these ideas to really just make art, look into artists from history who explore these themes, and don’t be afraid to push your ideas. Every work you make will make you more confident in finding your path forward. These are topics with a wide breadth of interpretations, so there’s many ways to approach these themes. It’ll be a long process to figure out where and how you want to explore these ideas, but you will find your path.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.