Ozma Van Het LLum // The House of NonSense

Where do you live: Currently based in Spain, but always somewhere else—between places, drifting through many other possible lives.

Your education: Linguistics and Translation; Gestalt Counseling and Art Therapy; Kundalini Yoga

Describe your art in three words: Questioning · Intuitive · Poetic

Your discipline: Analog Collage / Mixed Paper Practice

Website | Instagram | Instagram

Your biography feels poetic and fragmented, much like your collages. How does your life experience shape the way you assemble images?

My life has always unfolded in fragments: languages, places, movings, jobs, identities, phases that don’t follow a linear narrative. So, I guess, collage naturally became my way of making sense of that and of recomposing myself. As a translator, a traveller and a linguist, I’m used to working between meanings, inhabiting gaps and ambiguities. When I assemble images, I’m doing something similar: I let fragments speak to one another, allowing intuition, memory, and lived experience to guide the composition rather than logic alone.

Ozma Van Het LLum // The House of NonSense | reLOVEtion

Ozma Van Het LLum // The House of NonSense | reLOVEtion

You describe yourself as a paper lover and a collage maker. What is your relationship with paper as a material and as a carrier of memory?

Paper is a living material to me. It holds nature itself—time, touch, erosion, intention. It creases, yellows, tears, and in doing so, it remembers. I’m deeply attached to its fragility and its resilience at the same time; it often feels like a mirror of the human soul. Working with paper is an intimate act—almost like listening to what it has already lived before asking it to become something else. Much like life.

Ozma Van Het LLum // The House of NonSense | Cosmic Dancer

Ozma Van Het LLum // The House of NonSense | Cosmic Dancer

Many of your works are built from recycled images and fragments from the past. What draws you to what has been left behind?

Since I was a child, I have been fascinated by the appearance and presence of my ancestors—their gestures, their belongings, their way of inhabiting the world. My great-grandparents were born at the end of the 1800s, and I feel that I carry the traditions of many generations within me. Perhaps that is why I am so captivated by abandoned pieces of the past. What is left behind often holds the strongest emotional charge—soulful stories, forgotten meanings. Discarded images, freed from their original function, become open, available, unresolved. I am drawn to their silence and latent potential. Working with them feels both like an act of rescue and of re-signification: offering them a new voice, a chance to speak another language.

Ozma Van Het LLum // The House of NonSense | Amsterdam

Ozma Van Het LLum // The House of NonSense | Amsterdam

You mention “reassembling the scattered pieces of the world.” Do you see collage as a form of healing, archaeology, or storytelling?

I see collage as all three at once. There is something archaeological in digging through images and layers of time; something healing in reconnecting fragments that were once separated; and something deeply narrative in the final composition. It is a way of honoring the lives of those who came before me, who left behind pieces of their existence for me to carry forward. Collage also allows me to gather parts of myself that feel anachronistic—sensibilities seemingly stranded in times I never lived, like the Roaring Twenties or the Swinging Sixties—and let them coexist. It lets me create meaning without closing it, leaving what was broken visible, altered, and still in motion.

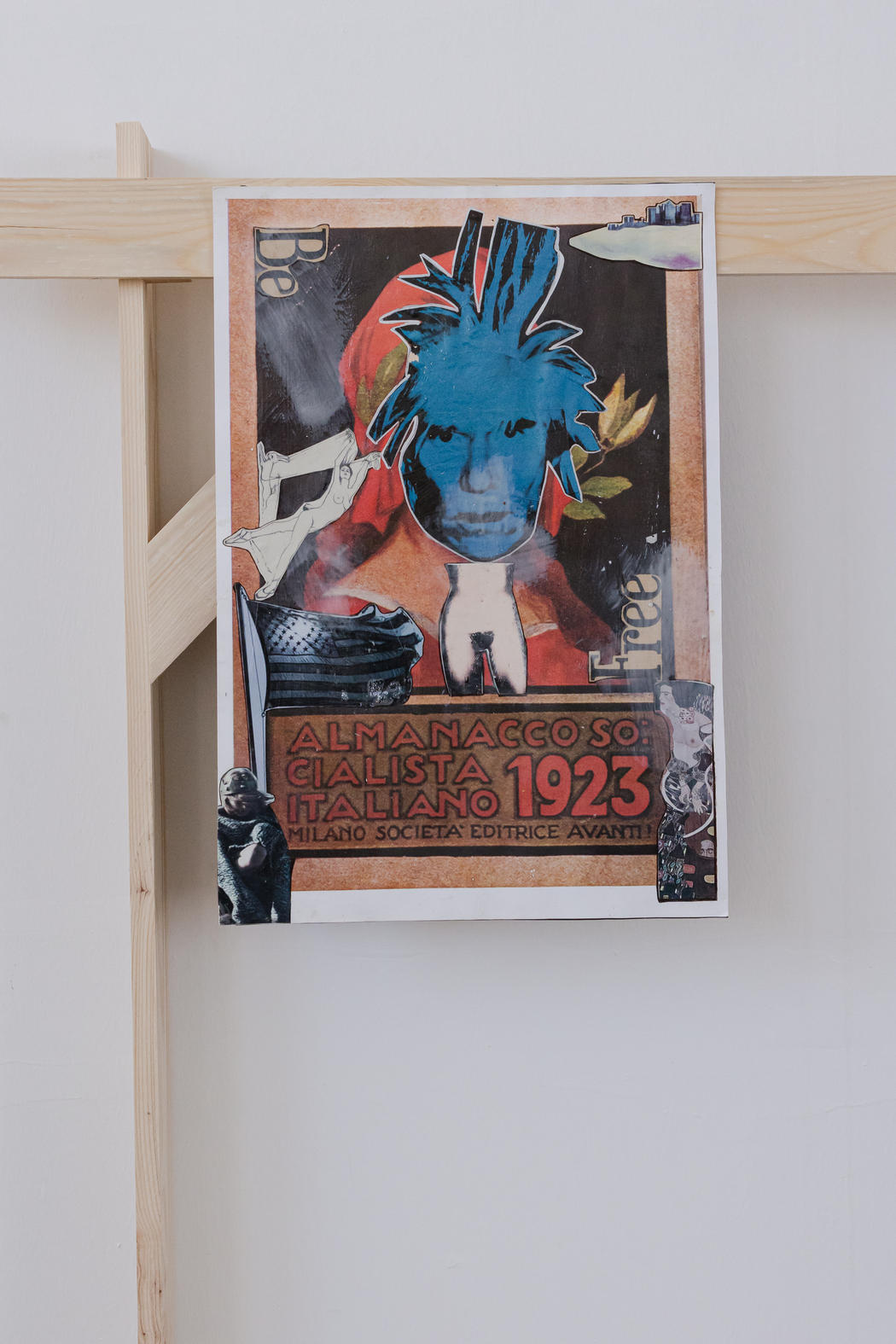

Ozma Van Het LLum // The House of NonSense | Arise My Love // from the AVANTI! series

Ozma Van Het LLum // The House of NonSense | Arise My Love // from the AVANTI! series

Language seems important in your life — as a translator, linguist, and sometimes poet. How does language influence your visual practice?

From a very young age, I realized—quite unexpectedly—that some parts of me could only express in other languages, specifically English and French. As I grew, I discovered that certain words exist only in a particular tongue, carrying nuances that cannot be fully translated; without them, the feelings or situations they describe would remain inaccessible. It was a revelation. Since then, language has shaped the way I see the world. Translating taught me that meaning is never decreed, that every word carries shadows, echoes, and excess. This awareness flows into my visual work: I think in syntax, in pauses and silences, in metaphors. My collages often function like sentences that resist a single interpretation—they suggest, they unfold, they invite the viewer to linger.

Your works often feel suspended between nostalgia and reinvention. How do you balance respect for the original images with transformation?

I try to listen carefully to the images before intervening. I don’t want to erase where they come from; instead, I aim to preserve their essence while shaping them into something different. Transformation, for me, is a dialogue: traces of the original context remain, even as something unexpected is allowed to emerge.

Nostalgia is a complex, bittersweet emotion—often described as the happiness of being sad—rooted in the graceful acceptance of what is gone. It becomes fertile only when it opens a door onto the present, and my work seeks to keep the past alive in a new form—one that can continue to live, breathe, and speak in the here and now.

Ozma Van Het LLum // The House of NonSense | Be Free // from the AVANTI! series

Ozma Van Het LLum // The House of NonSense | Be Free // from the AVANTI! series

What emotions or questions do you hope viewers carry with them after encountering your work?

I hope they leave with a sense of gentle disorientation—a feeling that something has shifted slightly. Not answers, but questions. A moment of recognition, perhaps, or estrangement. Above all, I hope the work awakens curiosity: a desire to linger, to dig into the layers of meaning, to follow the fragments that spark the wish for more. Perhaps the truest aim of my practice is to remind viewers that nothing is fixed—everything can be questioned, changed, or reimagined from one’s own perspective. I hope those who encounter my work feel inspired to create their own universe, to explore their own fragments, and to discover the possibilities that exist between what is and what could be. If my art creates space for introspection, memory, or a new way of sensing the world, then it has done what it needed to do.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.