Michelle Alexander

Where do you live: Chicago

Your education: MFA- School of the Art Institute of Chicago; BFA- University of Miami; AAS- Parsons, New School

Describe your art in three words: Intimate · confrontational · visceral

Your discipline: Installation / sculpture / mixed media

Website | Instagram

Your work explores the body’s responses and the tension between inner and outer experiences. How did this focus on the body begin in your artistic practice?

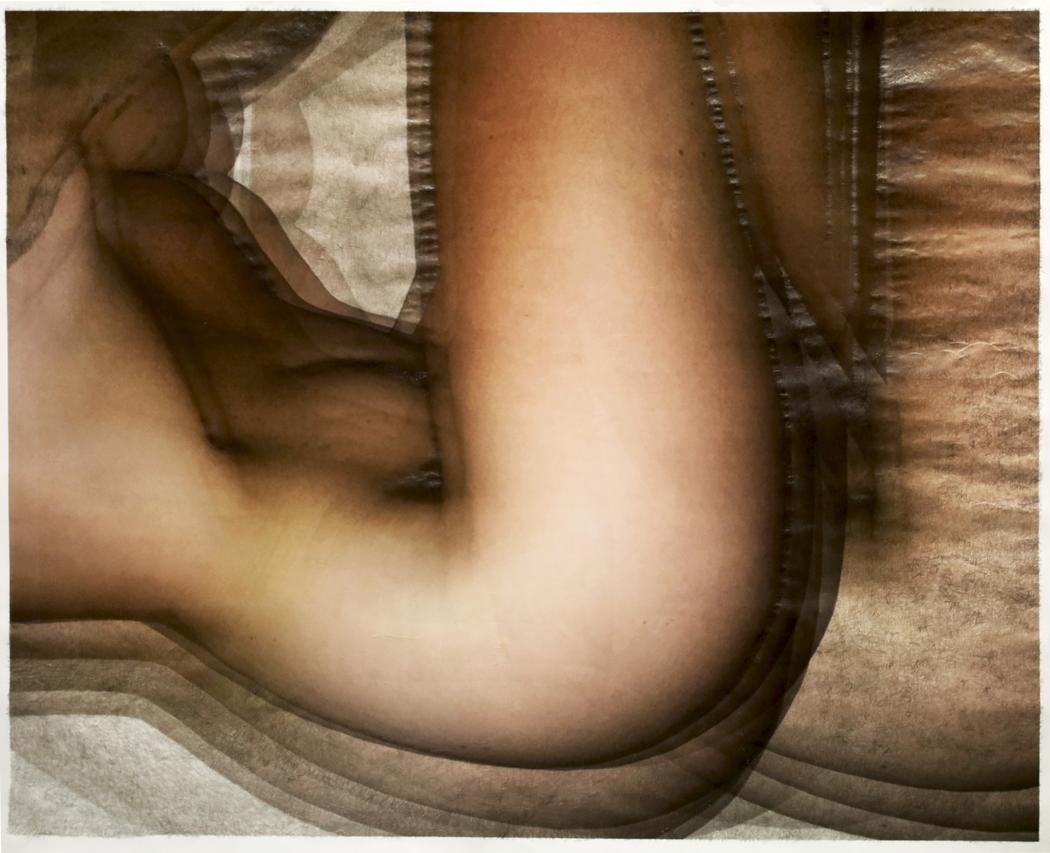

It began when I noticed that my body was reacting long before I understood why. Anxiety surfaced as tightness in my chest, a shaking hand, or a sudden heat rising under my skin. I became hyperaware of these small betrayals. My body felt unreliable, as if it was working against me at the moments I needed it to stay composed. Eventually, I recognized those reactions as a kind of vocabulary. My body was communicating in signals I had spent years trying to ignore. Working with it became a way to give form to what I could not yet articulate. The body stopped being a subject and became a language, one that let me name what had previously been unspoken, avoided, or suppressed.

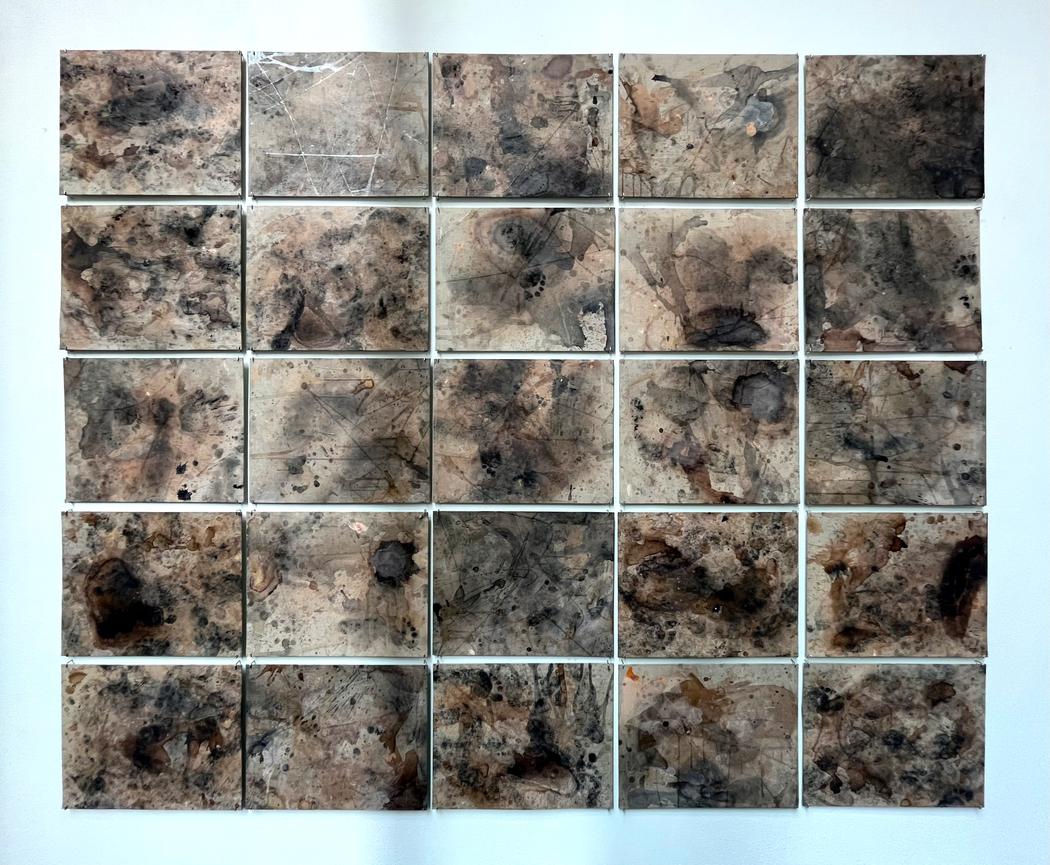

Michelle Alexander | The Pressure | 2025

Michelle Alexander | The Pressure | 2025

You describe your work as a process of making the unseen visible. What does “the unseen” represent for you personally?

For me, “the unseen” is the emotional residue we carry but rarely show: anxieties lodged in the gut, the feeling of being displaced inside your own skin, the quiet instability beneath a composed exterior. It’s also in the contradictions, how you can feel fragile and heavy at the same time. My work tries to give form to those internal states that don’t have a clear physical counterpart but deeply shape how we move through the world.

How do personal experiences of discomfort or being “confined in one’s skin” influence the materials and forms you choose?

Discomfort has shaped the way I choose materials. I am drawn to things that look delicate or shell-like, materials that could easily be dismissed as fragile, decorative, utilitarian. I take those elements and devalue them on purpose, altering or distressing them so they carry a different weight. Fabrics, wigs, resin, and other skin adjacent surfaces become stand-ins for the body, but also for personal history. They stretch, sag, crack, or resist control, much like the body does under pressure. The forms often emerge from negotiating with these materials rather than mastering them. The sense of being confined, held in, or held back becomes literal. The materials mirror the internal experience of discomfort, but they also hold the memory of what they once were, and what they are forced to become.

Michelle Alexander | Studio

Michelle Alexander | Studio

You mention a “crumbling self-image” and the struggle to reclaim identity. Do you view your art as a form of healing or confrontation?

I see it as both, but confrontation usually comes first. Making the work forces me to face parts of myself I’ve tried to push aside like fear, shame, doubt, and vulnerability. Only after that confrontation is there room for healing, and even then, the healing is not neat or complete. It’s more of a reclamation: taking ownership of the fragments rather than hiding them. The work becomes a place where I can sit with the instability instead of trying to fix it.

You treat materials almost as a body — as skin. What materials do you find most effective for translating these bodily associations and why?

Fabric, glue, and soft plastics are the materials that feel most connected to the body in my practice. They behave like skin: thin, elastic, and always on the verge of giving out. Fabric is where memory settles. It creases, stretches, and carries the imprint of whatever has touched it. Glue has a fleshy quality. It thickens, sags, and resists in ways that echo muscle or tissue struggling to hold something together. Soft plastics feel almost dermal. They seal, protect, and create a surface that looks stable, yet can split or warp without warning. These materials do not simply reference the body; they perform like it. They respond to gravity, pressure, and time. They shift, fail, and endure. That instability is what makes them so effective. They capture the tension of inhabiting a body that is both container and constraint.

Michelle Alexander | Stain | 2023

Michelle Alexander | Stain | 2023

In your installations, objects often clash or create friction. What role does conflict play in your creative process?

Conflict is not something I add for effect. It is already present in me, so it shows up in the work. I am always caught between wanting to disappear and wanting to be seen, between holding it together and letting everything fall apart. That push and pull becomes physical in the studio. Materials fight for space. Structures sag, scrape, or strain against what they are supposed to support. When things do not sit neatly, when the work looks like it could shift or fail, it feels honest. That friction is the truth of living in a body that is never fully at ease. The tension is not a problem to solve. It is the point.

Michelle Alexander | Scratching Away | 2021

Michelle Alexander | Scratching Away | 2021

You create spaces where the viewer can “see themselves and be seen.” What kind of emotional response do you hope visitors experience when encountering your work?

I am not interested in making people comfortable. I am interested in making something felt. I want viewers to recognize themselves in the work, even if they do not have the language for it. I want them to notice their breath, their stance, the twitch of a muscle they did not realize was tense. The work should draw them in and unsettle them at the same time. I am never trying to hurt anyone. I am trying to create a space where reckoning becomes possible, where something that has been buried or ignored finally surfaces. If they walk away carrying a sensation they cannot quite name, or a sharper awareness of the tensions they live with, then the work has done what it needed to do.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.