Ophelia Chen

Where do you live: Los Angeles, CA, United States

Your education: Master of Fine Arts — ArtCenter College of Design

Describe your art in three words: Speculative · Poetic · Futuristic

Your discipline: Digital media, virtual reality, spatial interfaces

Website

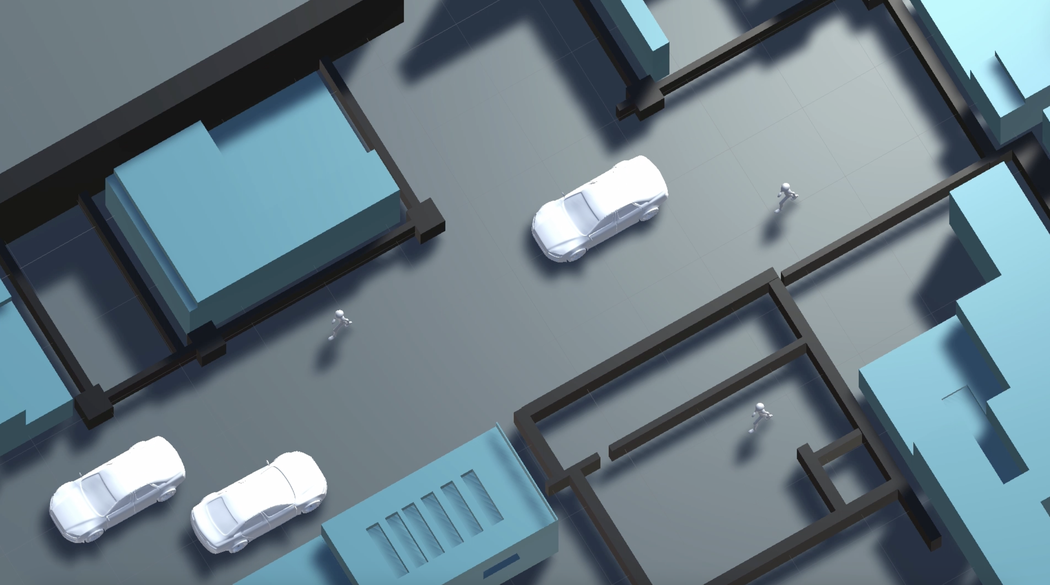

Ophelia Chen | Leftover Lots | 2024

Ophelia Chen | Leftover Lots | 2024

What initially drew you to working with VR and spatial interfaces as your primary artistic medium?

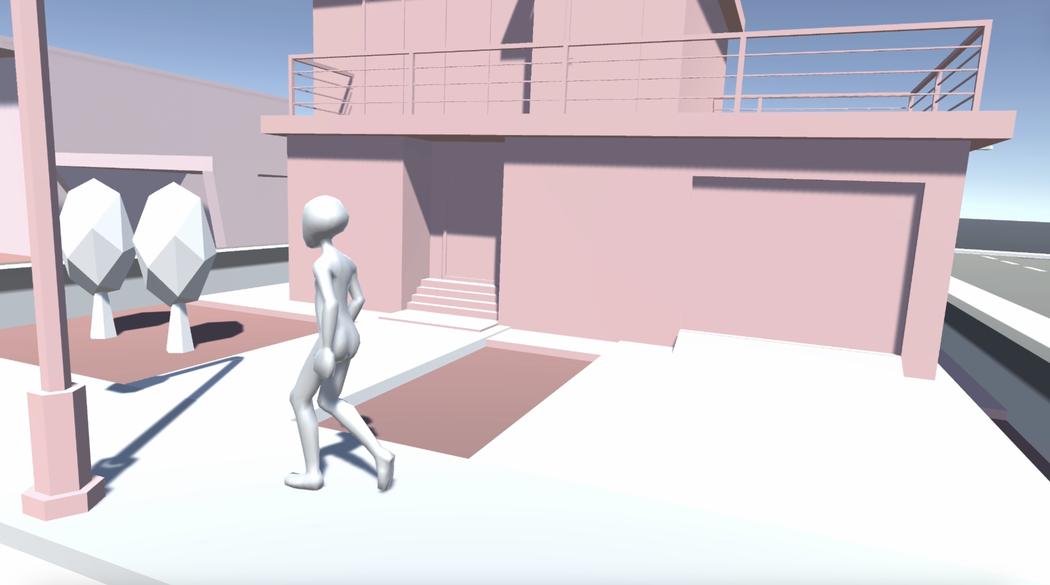

I was drawn to VR because it allows me to move beyond representation and into the realm of experience. When we talk about urbanism or the future of cities, diagrams and renderings often feel distant. I wanted to bring the conversation to life by placing the audience directly inside the speculation.

Spatial interfaces allow me to connect with the viewer on a visceral level. It isn’t just about looking at a future city; it’s about inhabiting it. By immersing the audience in this infrastructure, I can inspire a deeper emotional response and bring up a conversation about how we want to live. VR transforms the “what if” into a “here and now,” making the abstract concepts of future mobility feel tangible and immediate.

How did the idea for this project emerge, and what moment or observation first made you question the future role of autonomous vehicles in shaping cities?

The project, Leftover Lots, began with an observation of the present: autonomous vehicles (AVs) are increasingly appearing in our cities, yet our infrastructure remains static. We tend to think of AVs merely as “driverless cars,” but I started asking the more extreme “what if” questions. What happens when the transition is complete? What if all vehicles become autonomous?

I realized that if mobility becomes entirely fluid and self-organizing, the very concept of “parking” becomes obsolete. This sparked the central inquiry of the project: looking at a city that no longer needs to store dormant machines. I wanted to explore a future where cities breathe and move, animated by a fluid web of mobility rather than being choked by static pavement. It was a realization that we aren’t just changing cars; we are on the precipice of changing the fundamental geometry of urban life.

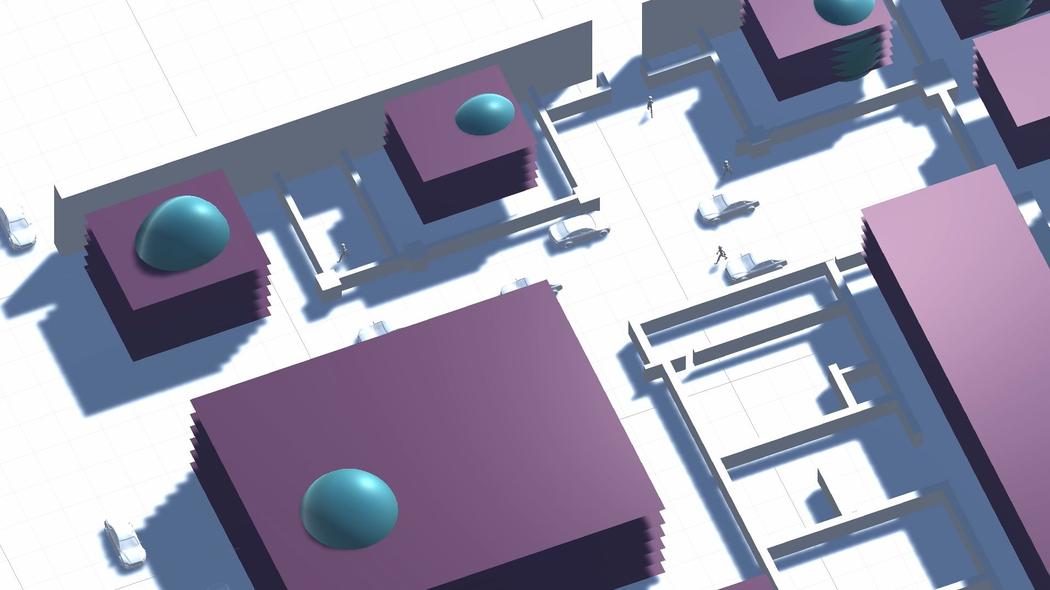

Ophelia Chen | Leftover Lots | 2024

Ophelia Chen | Leftover Lots | 2024

Your work blends cinema, installation, and interaction design. How do you balance narrative intention with user agency inside immersive environments?

My goal is for the audience to stop feeling like spectators and start feeling like inhabitants. I want them to imagine they are co-authors of this storytelling experience. In Leftover Lots, the “narrative” isn’t a linear script; it is the environment itself.

By allowing the user to navigate this immersive infrastructure, I give them the agency to discover the logic of this new world at their own pace. The architecture acts as the storyteller. Whether they are moving through a “mobility hub” or a “shared modular housing” unit, they are piecing together the story of this civilization. I try to balance my design intention with enough openness that the viewer feels they are living in this future, rather than just watching a movie about it.

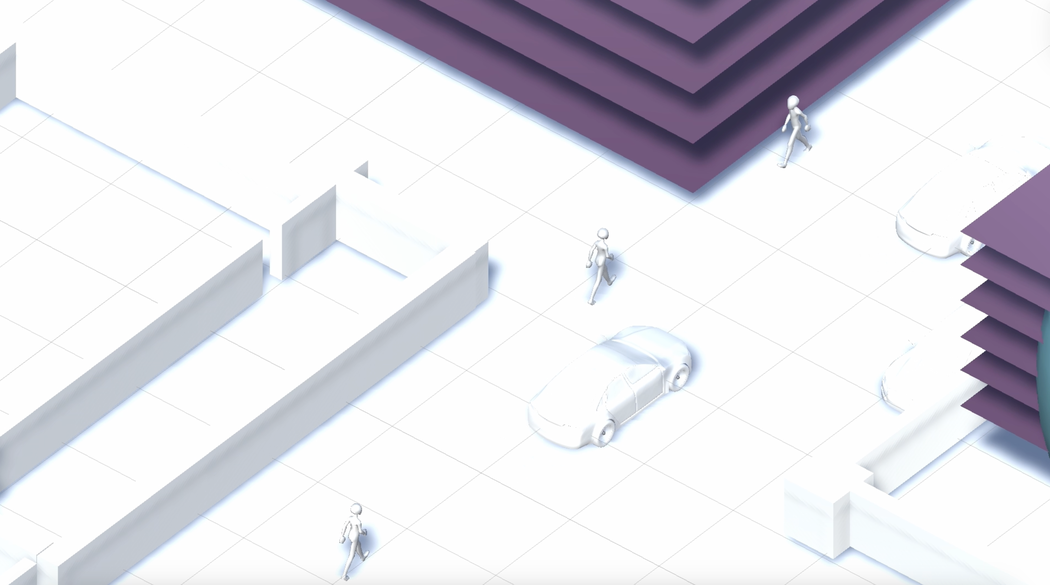

Ophelia Chen | Leftover Lots | 2024

Ophelia Chen | Leftover Lots | 2024

In your vision of a post-parking city, what aspects of urban life do you imagine changing the most — socially, visually, or emotionally?

I believe the most profound shift will be social. A change in mobility is a change in civilization structure. We have to ask: will this fluid mobility balance our social structures, or will it enlarge inequality? Will it make the city more affordable and accessible, or create new tiers of privilege?

Drawing inspiration from historical precedents like the Egyptian city of el-Amarna, which used grid systems to enforce order, I am interested in how our future grids will shape behavior. I hope to revive a sense of humanity in this new urbanism, ensuring that as we optimize for efficiency, we don’t lose the “villages” and diverse constellations that make a city feel human.

Ophelia Chen | Leftover Lots | 2024

Ophelia Chen | Leftover Lots | 2024

What kind of research or real-world urban studies informed your speculation about future mobility systems?

My research process was a blend of technical study and personal documentation. I started with a “parking mood journal,” documenting the emotional texture of current parking typologies—angle, parallel, and perpendicular.

For the primary visual research, I utilized a technique of architectural overlay. I took photographs of real parking structures near my community and physically sketched over them using transparent paper. I categorized these spaces into time-sensitive sections—temporary parking, loading zones, and permanent structures—and then reimagined how those footprints could transform.

Secondary to this, I conducted technical research on the development of autonomous vehicles, including their size, turning radius, and emerging technologies. This grounded my speculative designs in reality. I moved through a progression: base, mass, tweak, sculpt, and form. This ensured that even my most abstract ideas, like the “rhythmic hierarchy” of the city, were built upon the physical reality of the existing urban grid.

The environments you build often choreograph the viewer’s movement and attention. What sensory or spatial tools do you rely on to guide participants without explicit instructions?

I rely heavily on the concept of the “grid” and modularity to guide intuition. Inspired by Howard Gardner’s “frames of mind,” I treat each modular element in the VR space as a way to organize human senses. I use lighting, scale, and “rhythmic hierarchy” to subtly direct attention. For example, the repetition of modular elements creates a pattern that the eye naturally follows, acting as a visual breadcrumb trail. By manipulating order and disorder—breaking the grid or stretching a form—I can signal to the viewer where to look or move next. It’s about creating an “elemental portrait” of a human being within the architecture; the environment stretches, expands, and secures the viewer, choreographing their movement through the feeling of space rather than through arrows or text.

Ophelia Chen | Leftover Lots | 2024

Ophelia Chen | Leftover Lots | 2024

What role do you believe artists and designers should play in imagining the future of urban infrastructure and mobility?

We have a responsibility to be provocateurs. While engineers solve for efficiency and city planners solve for code, artists must solve for humanity. We are here to inspire, to advocate, and to ignite conversation before the concrete is poured.

When massive developments in AI and automation are happening, there is often a rush to implementation. Artists have the unique ability to pause that process and ask, “Is this the future we actually want?” By visualizing the consequences—both the utopian and the dystopian—we provide a space for critique and imagination. My role is to bring the dynamic, human side of new urbanism to life, ensuring that the future of our cities is designed for people, not just for machines.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.