Carmen Samoila

Where do you live: Calgary, Alberta, Canada

Your education: Self-taught artist with an early foundation in sculpture, jewellery, stained glass, and illustration. Further training through workshops in painting, drawing, and printmaking.

Your disciplines: Painting, mixed media, cyanotype, and analogue and darkroom photography—held in a practice that moves fluidly across boundaries of form, guided by intuition toward unexpected discoveries and meaning.

Describe your art in three words: Mystery, Radiance, Resonance

Website | Instagram | Instagram

Your Blueborne series uses botanical elements and light-sensitive emulsions. Can you walk us through your process of creating these pieces outdoors?

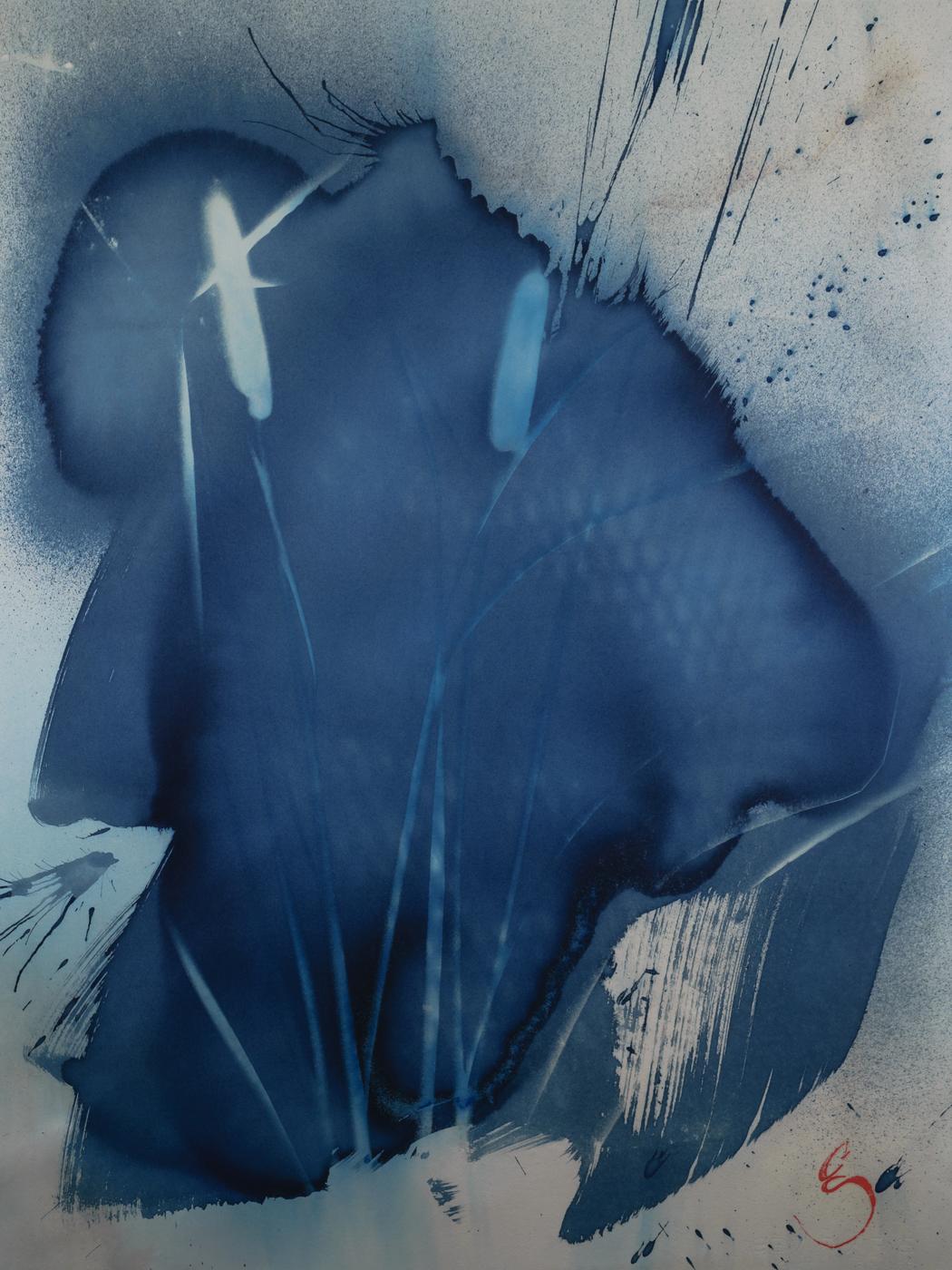

The Blueborne series begins with mixing the cyanotype formula, a union of iron compounds that, when exposed to UV light and washed in water, oxidize into the deep blue of Prussian pigment. I hand-coat BFK Rives fine art papers in a dimly lit studio, treating the emulsion not as a neutral ground but as paint itself. Brushstrokes form the first gestures of composition, so that each sheet carries a distinct rhythm before it ever meets the sun. Once dried, the papers are sealed in lightproof containers, awaiting their encounter with landscape.

For Blueborne, these prepared sheets travelled with me from Alberta into the mountains of British Columbia. Along the way, I gathered botanicals—reeds, grasses, flowers, wind-fallen leaves—each bearing the trace of place and season. In makeshift outdoor studios, I arranged these forms in intuitive choreography, securing them beneath glass to hold them steady in shifting light. The exposures unfolded under the high-altitude sun of the Kootenays, where rain, wind, and passing clouds shaped the image as much as my hand.

When the glass is lifted, the paper reveals a pale green impression that, once washed, transforms alchemically into the vivid Prussian blue of oxidized iron. I toned the works with coffee, softening the blue into a muted indigo more resonant with the landscapes themselves. Each piece dried in shaded open air, carrying subtle textures left by its environment. From beginning to end, the process remains tactile and elemental—brush, sun, water, plant, air—each print a singular record of its own making. I complete them with a cinnabar seal carved by hand, marking their vitality as part of Blueborne: a field record where material and place converge.

Carmen Samoila | Blueborne Vestige | 2025

Carmen Samoila | Blueborne Vestige | 2025

How does working in close connection with the natural landscape of Western Canada influence your practice?

The Western Canadian landscape is an active force in all of my work. The drifting skyline of the prairies, the boreal forests of the north, windswept passes of the Rockies, the temperate valleys and dry forests of the Okanagan, and the lush mists of the Kootenays each carry their own light, atmospheres, and rhythms—metaphors for the inner terrains I navigate. These vast expanses—the shifting shadows of mountains, the cool breath of alpine waters, the long northern glow through spruce and pine—sharpen my awareness of subtle transitions: the way light alters before and after a storm, how air grows heavier or thins at elevation, how stillness can vibrate with unseen movement.

My origins in the prairie regions of southern Alberta, along with formative years in the forests of the Yukon and British Columbia, have left me with a lasting sense of belonging to the land. Now, at home in Calgary, a city whose energy and community I share, I encounter the compression of urban life. Its pace, interruptions, and layers of daily maintenance can pull me away from the grounded attunement I find in nature. The city connects me to humankind; the land remains my muse, drawing me back to the earth and to myself.

This interplay shapes all of my series—from Blueborne cyanotypes created in direct collaboration with wind, sun, and gathered botanicals, to oil landscapes where light and weather are distilled into gesture and tone. Whether working in cyanotype, photography, painting, or sculpture, the external landscape and its ecosystems—and their reflection within—draw me inward to a place of discovery. In wild terrain, solitude opens space for intuition to lead. In the city, structure offers its own pulse and counterpoint. My work moves between these worlds, navigating thresholds where outer and inner converge. Each piece becomes a tactile map of memory and the living world that holds us.

You mention following intuition and responding to what “stirs beneath the surface.” How do you know when a piece is complete?

Completion, for me, is a recognition—an internal shift when the work begins to breathe on its own. I enter the process listening for what is asking to be revealed, moving between action and pause. There is a call and response: the piece speaks through its form, gestures, textures, and tonal balance, and I answer in turn. What stirs beneath the surface is the essence I seek—that vibration where I feel in alignment with the nature of our place in the universe, connected to the whole rather than to fragments of humanity.

When I began the Blueborne series, I created more than thirty experimental cyanotypes at locations ranging from open prairie to mountain lakes and forest edges. In my eyes, twenty of them failed. Four, however, stood apart—exquisite in their cohesion, connected not only through visual language but also through the manner and conditions in which they were made. Formed in the same spirit—through aligned timing, intention, materials, and light—they carried a natural harmony in gesture and tone. These became the heart of Blueborne. Another six will join the series soon, forming an intimate companion within Blueborne—where turmeric emulsions converge with cyanotype chemistry to extend its field of light.

It is rare for a work to become more than image or object—to hold the exact atmosphere of its making, the unrepeatable alignment of place, gesture, and time. In those moments, the work holds its own force, becoming a singular record of its becoming.

This is the nature of experimental work: its lessons are revealed in process. In Blueborne and across all my media, I’ve found that the purest expression often arrives in the first energy and gesture—the moment when the feeling is most alive. As the process unfolds, surges of possibility can lead me to add or subtract, to push and pull, sometimes clouding that initial clarity. Yet even this has value—it teaches me to recognise when I’ve gone too far, and how to return to what is essential.

Knowing a piece is complete is both experience and intuition. It is a recognition of expression, felt as much as seen. My breath shifts, my hands still, and I simply stand before the work, aware of its energy settling. That threshold between making and letting go is as integral to the practice as the first gesture. Each completion is a quiet resolution—a pause before the next beginning.

Carmen Samoila | Blueborne Penumbra | 2025

Carmen Samoila | Blueborne Penumbra | 2025

Your statement speaks of “luminous shadows” and “thresholds unseen.” How do these metaphors translate visually in your work?

“Luminous shadows” and “thresholds unseen” name the spaces in my work where contrasts converge—light with dark, form with dissolution, the known brushing against the unknown. They describe a heightened state of perception: moments when what is visible meets what is not.

While these metaphors move across my painting and photography as well, in Blueborne they become especially tangible. “Luminous shadows” are carried in the indigo depths of cyanotype—the radiant darkness shaped by impressions of botanicals, fragments of glass, and shifting light. “Thresholds unseen” emerge in the process itself: those brief alignments of wind, light, and form during exposure, when the image is not yet visible but already forming.

They also speak to the nature of liminal states—both in landscape and in self. A subtle radiance in darkness, the afterglow of a storm, a glimmering edge where structure dissolves. The line where horizon meets sky, the edge between land and water, or the tension before a choice is made. These are moments when stillness pulses with potential, when presence feels charged.

Together, these metaphors reflect the threshold nature of my practice: each piece a singular record of life-force, made in collaboration with the elements, holding the convergence between what is seen and what can only be sensed.

Carmen Samoila | Blueborne Matrice | 2025

Carmen Samoila | Blueborne Matrice | 2025

The use of coffee and pigment toning adds warmth to the cyanotype palette. What led you to experiment with these techniques?

The use of coffee and pigment toning in Blueborne arose through both experimentation and necessity. The traditional Prussian blue of cyanotype is striking, but it did not reflect the atmospheres I encountered in the field. I was drawn instead to a more subdued palette—tones that feel weathered, muted, closer to indigo than to bright cyan. At its heart, cyanotype is an elemental dialogue of iron and light: a chemistry of oxidation and reduction, but also a metaphor—what light transforms, time and organic matter temper into permanence.

I first intensified the blues with hydrogen peroxide, then began toning with coffee, seeking greater depth and resonance. The warm grey of BFK Rives paper already softened the surface, but coffee introduced an added warmth and subtle unpredictability that felt true to the process itself. It drew the prints toward the dusky resonance of evening skies, the mineral shadows of stone, the felt atmosphere of place.

Toning became another layer of dialogue with the materials—an alchemy that embraces the imperfect, the weathered, the handmade. The chemistry shifts, the surface deepens, and the work carries both its origin in iron salts and its transformation through organic infusions.

As with ourselves, these changes reveal the work more truly: what endures, what dissolves, and what remains.

Carmen Samoila | Blueborne Lilt | 2025

Carmen Samoila | Blueborne Lilt | 2025

There is a strong sense of stillness and vitality in your work. Do you see your art as a meditative or healing practice—for yourself or for the viewer?

Walking in nature is often where the work begins—gathering botanicals, attuning to place, and entering into quiet conversation with the land itself. That attunement is meditative: centring, soothing, and alive with recognition. From there, stillness becomes both an entry point and a return. The work cannot be rushed—it asks me to wait on weather, on light, on time itself. That slowness draws me into a state of deep listening, where process becomes less about control and more about response. If a piece does not begin in meditation, the making itself becomes the meditation—a flow state, an elemental immersion.

I see the practice as a dialogue: between body and landscape, between the pulse of an inner terrain and the shifting conditions around me. Cyanotype especially insists on patience—the emulsion dries as it will, the sun moves as it pleases, shadows lengthen in their own time. To respond requires trust in what cannot be forced.

At its heart, my practice has always been a way to digest experience, to find light within shadow, and to use the act of creating as a form of healing. Each piece arises through this movement—from darkness toward illumination, from fragmentation toward coherence. In moments of stillness, something settles: the materials, the body, the mind. From that quiet, something new is born—work that has never existed before, yet carries the imprint of resilience and renewal.

Like Blueborne and all my work, the intention is not only originality but endurance: to create pieces that connect us to spirit, that hold the possibility of healing, and that speak across thresholds of time. If a viewer feels even a pause from the noise of the world—if they sense recognition of themselves in the work—then the process extends beyond myself. It becomes a shared threshold, a place where we can enter, breathe, and remember what endures.

How has your background in sculpture and painting informed your photographic and mixed media work?

My early grounding in sculpture taught me to think with the body—gesture in space, weight, vitality. That sense of physicality never left me; even in two dimensions I remain attuned to material as form, as structure, as something that shapes how the viewer feels it in their own body.

Painting, by contrast, trained me in atmosphere—how to hold space through colour, light, and the tension of surface. It gave me a way of listening to nuance, to transition, to the subtle charge between darkness and illumination.

As a sculptor, and earlier as a stained glass artist and jeweller, I often worked to the edge of what a material could withstand—chiselling stone, hardwoods, fossilised bone, and mammoth ivory to their limits, coaxing alloys, gemstones, and glass into vessels of distilled light—always seeking the moment when form transcends its raw material state. That impulse—to discover the hidden qualities of a medium—still lives in me. But in painting, mixed media, and photographic processes, I have learned a different discipline: to sense when a piece asks to stop just short of the edge, to recognise when the work itself becomes alive, whole, and resonant.

Photography, and cyanotype especially, opens me in another direction: imprinting time itself. Unlike paint or stone, which can be shaped at will, photographic processes depend on duration. Every exposure is a record of passing time—light shifting, shadows lengthening, chemicals transforming. What emerges is not only an image, but the trace of a singular instant—unrepeatable, elemental. Where carving and painting distil countless gestures into form, photography captures the imprint of time unfolding.

These disciplines converse within me: sculpture grounds the body, painting attunes perception, craft sharpens respect for limits, and photography records the fleeting passage of time. Together they form a continuum—matter, atmosphere, and duration—woven into how I approach mixed media practice today.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.