Yilin Zhang + Yixuan Liu

Year of birth: 1992 & 1994

Where do you live: San Francisco, USA

Your education: Master of Architecture, Cornell University; Master of Architecture, University of California, Berkeley

Describe your art in three words: Phenomenology · Transitional · Contextualized

Your discipline: Architecture

Your project “Almost Forgotten” begins with found objects and emotional fragments rather than traditional architectural plans. Can you tell us more about this unconventional starting point?

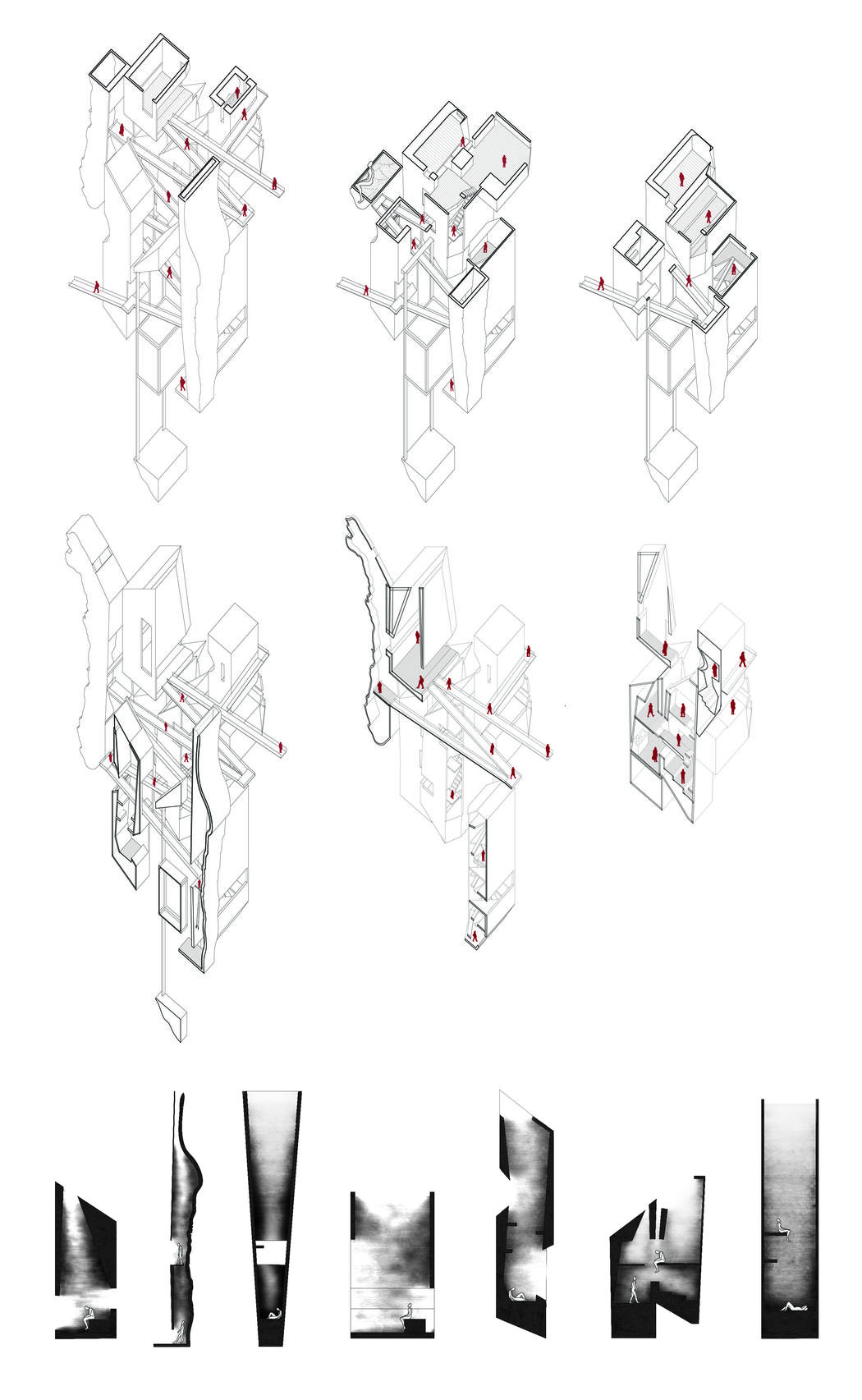

What began with found objects, things like pieces of timber, ragged fabric, discarded personal items, each already carrying a weight of time and a quiet narrative. Our inspiration was drawn from The Art of Memory which describes how spaces can be used to structure recollection, where shape can emerge from the raw arrangement of material, rather than from the planned abstraction. We tried to find clues to the atmosphere the architecture might hold from these sculptural elements: their scale, texture, and imperfections, etc. By physically composing these elements, we applied a methodology we have implemented across projects, one that merges curatorial sensitivity with spatial design, a combination rare in conventional architectural practice. In this way, the ‘building’ was not an object to be drawn, but an evolving assemblage of memory-charged pieces, slowly taking the shape of a place.

How do you see the relationship between memory, absence, and architecture in your work?

We see memory and absence as inseparable. Therefore, absence is often where memory gathers its strength. In Almost Forgotten, absence is not a void to be filled, it is a condition to be formed. Architecture augments a memory like a photo frame: it does not create the memory, it simply gives it a boundary in which it can be held and perceived. A wall, a shadow, a threshold, or so on can alert someone to that which is no longer there, allowing traces, silences, and fragments to remain alive.

The visual language of your project is both raw and poetic. How did you approach balancing structure and emotion in the final form?

For us, structure and emotion are two parts of the same anatomy. The rawness (exposed timber, fractured stone) isn’t an aesthetic decision, but a way to keep construction honest and legible. This synthesis of rigorous detailing with emotional intent has become a signature in our work, recognized for resonating across both architectural and artistic audiences. The poetics happen when that integrity achieves rhythm: the line of structure gives rise to light, or a joint becomes a point of tension.Every decision was tested against one question: did it achieve the maximum level of emotional response while maintaining a degree of integrity? In the end, emotion does not make structure soft; it gives it meaning.

What role does materiality play in evoking emotional responses in your spaces?

Our approach is based on Juhani Pallasmaa’s thoughts on architecture in his book The Eye of the Skin, but has developed into a repeatable working method that we have used in many different contexts. In his book, he recalls a moment when a person has returned to an old home, and they touch the weathered, slightly warped wooden handle of the front door, and suddenly, all at once, he finds himself swimming in a sea of feelings, memories, and security. We seek to make that moment deliberate. We see material not as a surface, but a vehicle of sensory memory. The textures of weathered wood, the thermal heft of stone, the cold slickness of metal, all of these are chosen, positioned and curated to re-evoke feelings that may have lain fallow for years. In Almost Forgotten, we showed that this methodology demonstrated how tactile qualities can exist as a structural part of architectural narrative, a strategy that is now being increasingly referred to in conversations with peers.

How does the process of designing in a cold, harsh landscape like the frozen gorge shape your spatial and artistic choices?

The frozen gorge calls for an architecture of humility. We could not compete with the scale, the silence, nor the severity of the landscape, so instead, we listened, a position that aligns with our practice of allowing site conditions to be co-authors of form. The cold attuned us to threshold moments: the shift from biting wind to sheltered stillness, from blinding snowlight to shadowed interior. We articulated spaces to amplify these moments of transitions, allowing shelter to feel earned and light to feel rare. The approach we’ve taken here has since informed our design approaches for other extreme climates, and has been cited as an example of turning environmental constraints into primary determinants of spatial experience.

Can you describe how the artistic model evolved into the architectural design? Were there any discoveries along the way?

We started with the wood pieces that had no specific scale. They weren’t models of architecture, they were sculptural explorations of mass, void and composition. As we moved toward architecture, we realized that form isn’t simply a container, but a process of mediation of body, memory, and site. The voids (the gaps, or cuts, or emptiness) in the model became as important as the solids. This shifted our view of form: in art, form can be an end in itself; in architecture, form is also an invitation, it frames movement, perception, and habitation. What we learned is that our most resonant spaces came not by adding more form to the design, but rather by allowing absence to be a part of the architecture.

Light and shadow seem to be key components in your project. How do you work with these elements to shape experience?

We treat light and shadow as temporal materials, always in motion, always reshaping the space. In our process, light is not applied uniformly; it is choreographed. Some spaces are deliberately kept dim, drawing the body inward and slowing perception; others are tuned to capture a brief, concentrated beam, making that instant feel monumental. Shadow also acts, it thickens space, softens edges, permits moments of stillness, etc. Achieving this orchestration requires technical fluency in structure, orientation, and material behavior, paired with an ability to choreograph them into an experiential sequence, a skill set that is relatively rare in the field but central to our practice.

How do you view the boundary between art and architecture, and how do you blur this boundary in your work? Why is this approach unique to the discipline of architecture?

We see both art and architecture as open for interpretation, they invite the viewer or inhabitant to project meaning and complete the work in their own mind. The boundary between them often exists more in institutional categories than in practice. By beginning with artistic processes (collecting fragments, working through abstraction, composing atmospheres) we let architecture emerge as a spatial art form rather than a separate discipline. Our ability to sustain conceptual ambiguity while delivering technically precise spaces is one of the defining capabilities of our work, ensuring that inhabitation becomes a form of participation in the artwork rather than simply the use of a functional shell.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.