Jason Lim

Jason Lim | Auto X2 Toned

Jason Lim | Auto X2 Toned

Your work often engages with the five elements. How do you approach translating these intangible forces into material or performative form?

The elements—earth, water, fire, air, and space—have always been quiet guides in my practice, but I also see them as participants in a kind of ongoing alchemy. I don’t try to represent them directly; instead, I create situations where they can be felt—where their presence shapes the process, the gesture, the form. When I work with clay, I’m working with earth—its density, its memory, its grounding force. Water softens it, invites change, teaches flow. Fire transforms it, sealing memory into permanence. Air and space offer breath, movement, and silence—they shape the atmosphere of performance, the invisible architecture around the body.

Taken together, these elements become a cycle of transformation—not just for the materials, but for myself as well. They move through stages of dissolution, purification, refinement. There’s something deeply alchemical in that rhythm: matter changes, and the self changes with it. My role is to listen, to respond, and to allow the work to be a meeting point between the visible and the unseen. In the end, I think of each piece as a residue of that elemental conversation.

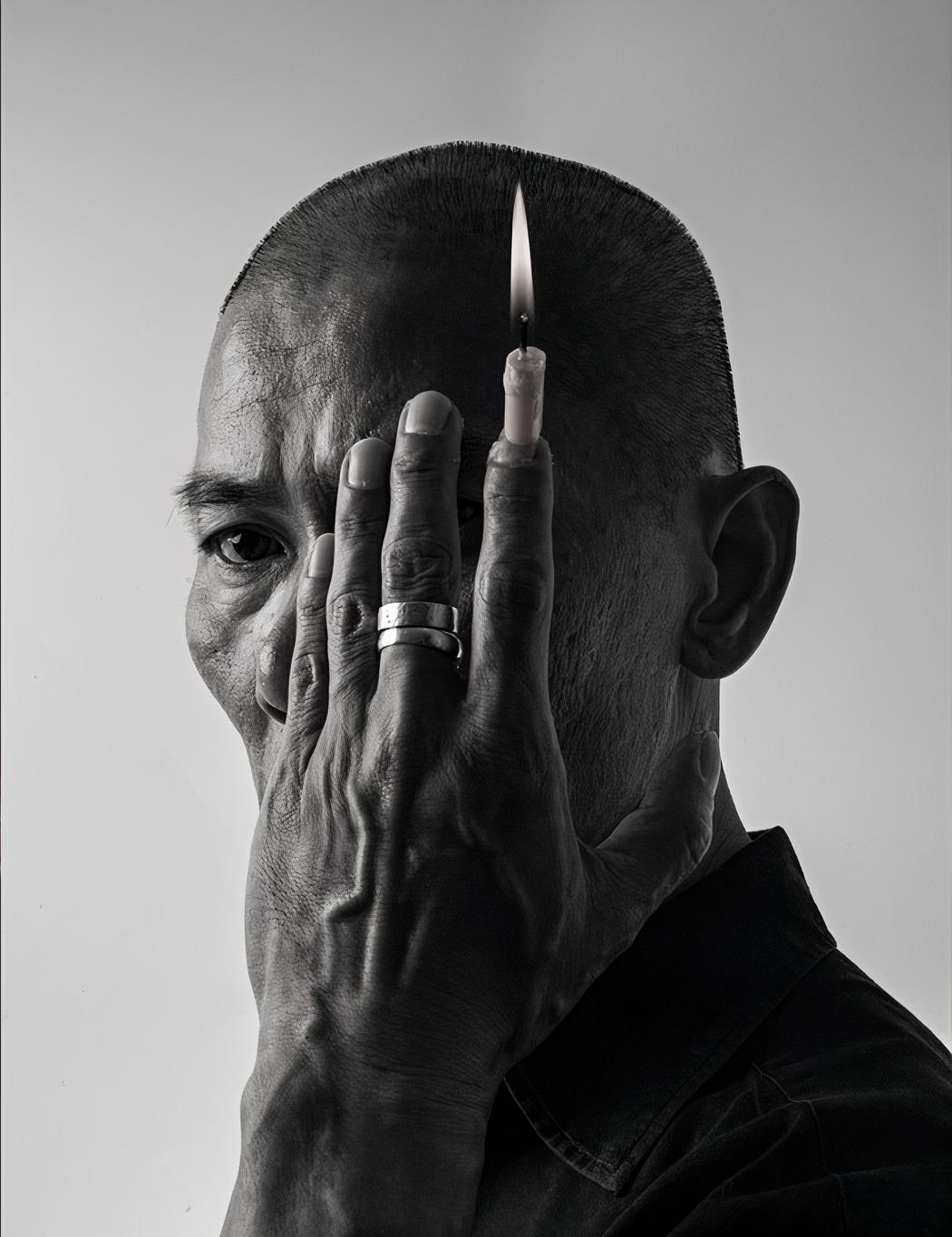

The piece we’ve seen here features a bell-like sculpture enveloping the performer’s head. What does this gesture symbolize for you?

That gesture came from an urge to create a kind of inward listening. The bell is often used to call attention—to mark time or summon presence. But when it covers the head, it changes everything. It muffles the world, turns the body into a resonant chamber, and draws attention inward. It becomes a space of pause, of retreat. For me, it’s about creating a moment of quiet concentration—a still point in a noisy world. There’s vulnerability in that too, in allowing myself to be both hidden and exposed.

At the same time, the image is created as a performance for the camera. I’m interested in how the image resists easy reading. It’s poetic, open-ended, ambiguous and almost dreamlike. It invites the viewer to project their own meanings onto it. So while the gesture is very much rooted in presence and embodiment, it also exists as an image—a kind of visual koan that asks, what does it mean to listen differently? What kind of silence is this? I don’t offer answers—I prefer to leave space for interpretation.

How do sound and silence function in your work — particularly in this bell installation?

Sound and silence are like two sides of the same coin in my work. I think of silence not as the absence of sound, but as something active—alive and charged with presence. In the bell installation, Tintinnabulation Series JDZ, sound becomes internalized. It’s less about what the audience hears, and more about what the performer feels: the amplified breath inside the bell, the vibration of a small movement, the imagined resonance when the bells are suspended and soundless. Silent space you can step into. It holds tension, memory and anticipation. I’m interested in how sound and silence can shape mood and perception. They slow things down. They ask us to notice more deeply.

Tintinnabulation Series JDZ was created during my residency in Jingdezhen in 2025. During this residency, I have also created a video work and the soundtrack is composed using the sounds of the bells themselves—their tones, resonances, and silences layered into a kind of auditory landscape. The images focus on the environment and people of Jingdezhen: the hands of craftsmen, old kilns, fragments of ceramics, both ancient and newly made. The footage moves between the intimate and the expansive—moments of stillness, gestures of making, and the quiet presence of place. The bells, both in sound and form, act as a bridge—connecting time, material, and memory. In this work, sound is not just something heard—it becomes a way of sensing, of remembering, and of honouring tradition.

Repetition and ritual seem central to your process. What does repetition mean to you as a creative act?

Repetition has always been a kind of grounding for me. It allows me to move past the surface of things. There’s something in the doing—again and again—that reveals layers you wouldn’t see otherwise. I see it as a kind of meditation, or maybe even a quiet form of resistance to the fast pace of contemporary life. Ritual enters when the repetition carries intention. Whether I’m shaping a vessel or repeating a movement in performance, it’s about finding presence in that loop, letting it evolve, letting it wear away at the unnecessary. It’s never the same—it’s alive, always shifting.

Jason Lim | Tintinnabualtion Series

Jason Lim | Tintinnabualtion Series

You often work with clay, yet your practice extends beyond ceramics into performance and film. What draws you back to clay again and again?

Clay is where I started, and it still feels like home. There’s a directness to it—a kind of honesty. It responds immediately to touch. It remembers pressure, warmth, even uncertainty. No matter how far I move into other media, clay keeps calling me back. It teaches patience. It collapses time. Working with it always reminds me of something fundamental about being human—about making, about fragility, about change. And because it’s such a grounded material, it anchors even the more ephemeral parts of my practice, like performance or video. Clay holds the quiet voice in all of it.

Could you describe how slowness and meditative action shape the development of your pieces?

Slowness is essential to how I work. It creates space—for the work to unfold, and for me to meet it as it changes. When I slow down, I begin to notice more: the shift of light across a surface, the small choices made without deliberate thought, the quiet conversation between hand and material. Meditative action keeps me present in those moments. Whether I’m shaping clay or moving through a performance, it’s not about producing something quickly—it’s about being fully inside the act of making.

Slowness brings with it a kind of intimacy. It allows meaning to gather over time, not through grand gestures but through repetition, stillness, and quiet attention. And perhaps most importantly, taking time also allows for reflection while the work is still in progress. It gives me the chance to listen—not just to the materials, but to myself. In that reflective space, new paths often appear. I come back to slowness again and again, not as a method, but as a way of being with the work—a way of allowing it to become what it needs to be.

You have worked across cultures and continents. How do local traditions or landscapes influence your practice?

Each place I’ve worked in has left its imprint. Sometimes it’s in the way a community approaches making—how skills are passed down, how care is given to the process. Other times it’s in how rituals are seamlessly woven into daily life, or how silence is held and respected. I don’t deliberately set out to incorporate these things, but they inevitably find their way into the work. It’s less about taking, and more about being shaped—by the rhythms, the textures, the spirit of a place.

Landscapes speak in subtle ways. The humidity, the dryness, the changing light, the tempo of the seasons—all of these affect how I move, how I feel, how I create. I pay close attention to sound too. Listening has become a big part of how I attune myself to new environments: the murmur of languages I may not understand, the noise of traffic, the rustling of leaves, bird calls at dusk, the way water moves through a space. These sounds carry stories, and they inform the pace and tone of the work, often in ways I only realize much later. In that sense, the work becomes a kind of dialogue—with place, with history, and with all that unfolds quietly in between.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.