Gerline Fourie

Year of birth: 2002

Where do you live: Plymouth, MA, USA

Your education: BFA in Teaching Arts ‘25 from Massachusetts College of Art and Design

Describe your art in three words: Explorative, Obsessive, Anatomical

Your discipline: Interdisciplinary Fine Art with a focus on Anatomical Imagery and Material Exploration

Instagram

Your work merges fine art with medical illustration. What initially drew you to this intersection?

I’ve always been fascinated by how the body functions, how intricate, fragile, and mysterious it is. When I began studying art, I realized that the visual language of medical illustration offered a way to express that fascination with precision and intimacy. It wasn’t just about anatomy; it was about the body as a site of meaning, memory, and sometimes discomfort. Merging fine art with medical illustration allows me to explore these themes in a deeply personal and material way.

How did your early experiences with anatomy influence your visual language today?

I grew up in a family of hunters, so I was exposed to anatomy in a very raw, physical way from an early age. I remember being both disturbed and fascinated by the process of skinning or cleaning an animal, how you could peel back the surface and suddenly see the inner structures that made life possible. It wasn’t clinical, it was messy, immediate, and very real. That shaped how I think about the body today, not just as a biological system but as something intimate and fragile. I was also exposed to the Body Worlds exhibitions in high school, where there was this exciting mix of science and spectacle. You’d see preserved organs, taxidermy, anatomical models, objects are meant to teach, but that also carried a certain theatricality. All of that filtered into my visual language: a mix of curiosity, reverence, and an impulse to look closer, even when it feels uncomfortable.

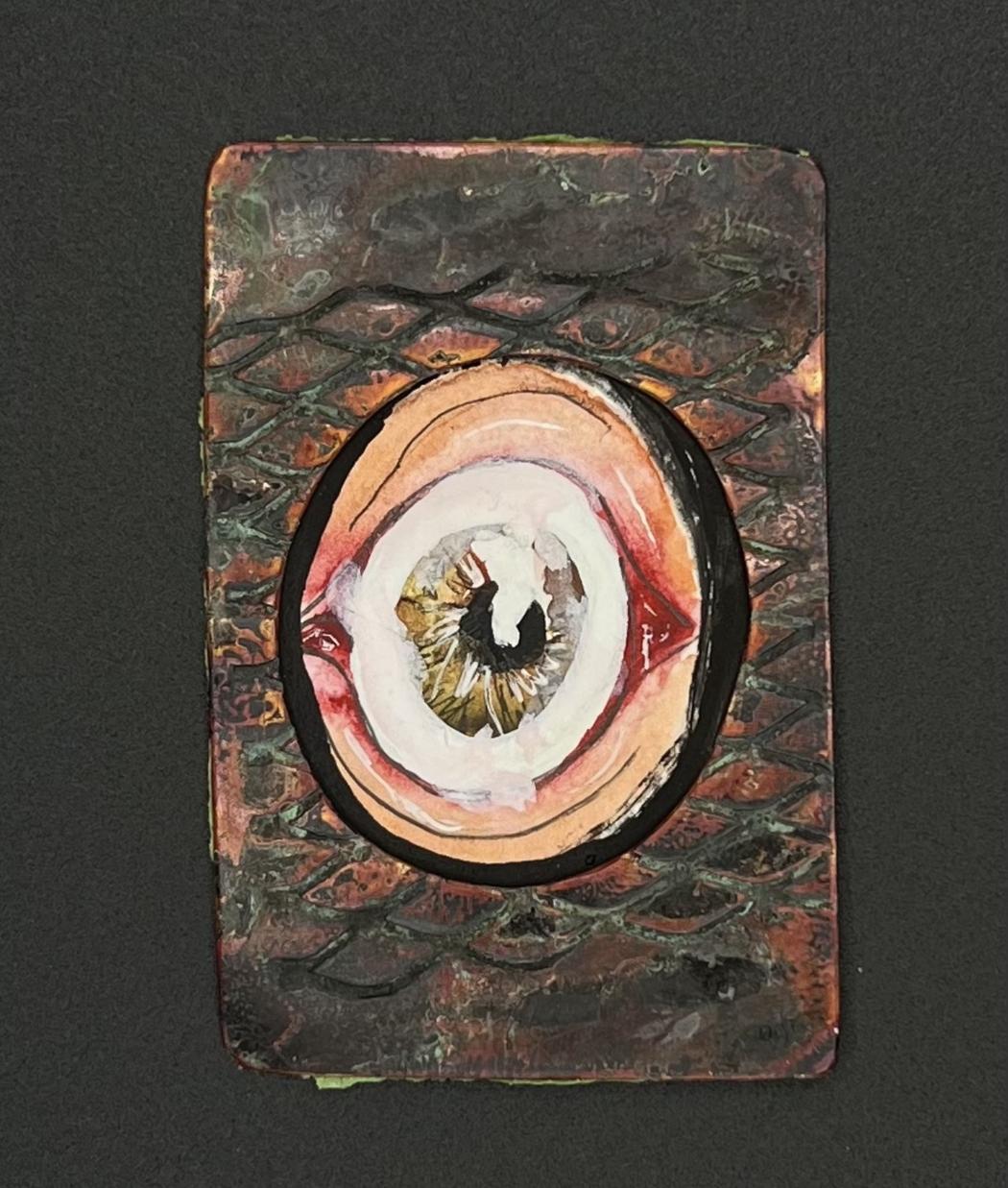

Gerline Fourie | Eyebrooch | 2025

Gerline Fourie | Eyebrooch | 2025

Your use of repeated eye imagery is striking. What emotional or symbolic resonance do eyes hold for you?

The symbolism is quite literal for me. The eye represents learning, seeing, and understanding; especially as someone who learns visually. In art school, so much of my education came from watching: watching demos, watching how materials behave, watching others work. The eye, as a motif, becomes a stand-in for that process. It’s about perception, but also surveillance, vulnerability, and the tension between being the observer and the observed.

In pieces like My Monocle and Framed Eye, there’s a mix of beauty and discomfort. Do you aim to provoke a visceral reaction in the viewer?

Yes, absolutely. I think beauty and discomfort are deeply connected, they often coexist in ways that are hard to untangle. There’s something compelling about that tension, something you can’t look away from. I crave that same response in my own work. Even if the viewer doesn’t understand it or necessarily enjoy it, I want them to feel something in their gut. I want the work to linger, to haunt a little.

Gerline Fourie | Framed Eye | 2025

Gerline Fourie | Framed Eye | 2025

How do you choose which materials—ceramics, embroidery, metal—to use for a specific piece?

Honestly, I feel like the piece chooses the material. Once I find a reference image (usually from a medical or anatomical textbooks) it almost speaks to me. It asks to be transformed, to exist beyond the page. Sometimes it wants the delicacy of thread, the weight of clay, or the cold sharpness of metal. Studio access also plays a role asduring undergrad I was fortunate to work in spaces that allowed me to experiment widely. That access deeply shaped the way I think about materiality.

What do you see as the main challenge in positioning educational or utilitarian imagery within the realm of fine art?

The main challenge is perception, people often separate “useful” images from “expressive” ones. Medical illustrations are traditionally seen as functional, not emotional or interpretive. But I see immense potential in recontextualizing that kind of imagery, taking something meant to explain and turning it into something that evokes. It’s about expanding the boundaries of what fine art can be, and who gets to decide that.

Gerline Fourie | My Monocle | 2025

Gerline Fourie | My Monocle | 2025

Your process involves repetition and obsessive detail. What drives this approach?

I think it starts with the materials, I get completely hooked. Once I learn how to manipulate a medium I enjoy, I want to keep pushing it, keep seeing what else it can do. That repetitive, almost meditative process mirrors how I engage with anatomy: the more I study, the more I realize how little I know. The human body offers endless complexity, and repetition becomes a way to both understand it and honor it.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.