Yanqing Pan

Year of birth: 2002

Where do you live: Michigan

Your education: Cranbrook academy of Art

Website | Instagram

Yanqing Pan | Man from crowd (人从众𠈌) | 2023

Yanqing Pan | Man from crowd (人从众𠈌) | 2023

How do you choose specific materials—like dust, orange peel powder, or wood—for each piece?

I often feel that materials are not “chosen” but rather withdrawn first, then quietly invited back. Dust, orange peel powder, wood—these are things so humble they almost vanish from notice, swept away by daily life and by civilization’s urge to clean. Yet they carry a quiet sense of the sublime: they do not make noise, but they keep proving that time and decay persist. I use them because they have the courage to grow weak in the open, even to disappear. That very retreat is, for me, the most honest form of strength.

You once said, “Working with decomposable materials is my way to explore what cannot be pinned down in words.” Could you share a moment when language failed you, and the work itself spoke more clearly?

Often, language is too sharp—it slices details apart. Once I tried to write about an apology I had never spoken out loud, but the more I wrote, the more distant it felt from the truth. Eventually, I buried that half-written page in damp soil. The paper softened, molded, dissolved, and even the ink faded away. In the end, only the smell of the earth remained. I feel that scent holds what no sentence could keep.

Yanqing Pan | L autre qui n est pas | 2025

Yanqing Pan | L autre qui n est pas | 2025

Your work has been described as “traces, gestures, or interruptions—barely-there presences.” How do you maintain subtlety while still leaving a perceptible resonance in the gallery space?

I rarely make my work speak loudly. I care more about whether people feel the air shift when they come close. I think of the gallery as a kind of skin—sometimes a faint smell, a sliver of light, or a glance caught at the corner of the eye can plant a quiet echo in someone’s mind. I trust the viewer’s body more than their attention. Especially nowadays, the first time a lot of works are seen by the audience is no longer because they are present, but often the first time is through the media, and the second time is in person. The second encounter is often nothing new, but just confirms what has been absorbed before. I try to explore what art becomes after being visualized and reproduced, but at the same time I also pay attention to how to sense art.

Growing up in Beijing, how did the city’s rapid transformation shape your sensitivity to environmental and existential change?

Living in Beijing, houses, alleyways, and street corners were constantly disappearing. Each demolition seemed to carry away familiar scents and sounds as well. It taught me a sense of instability early on, and helped me accept that change is the norm. I think that’s why my work often carries a texture that is always ready to dissolve.

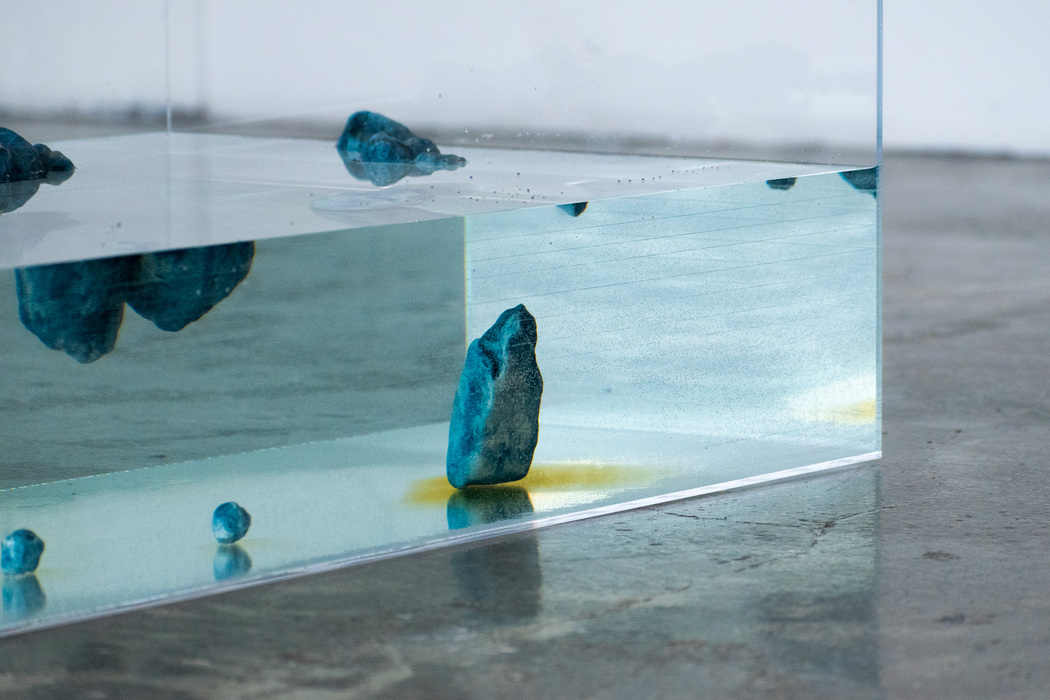

Yanqing Pan | Boundaries Dissolve in the Sea | 2024

Yanqing Pan | Boundaries Dissolve in the Sea | 2024

You moved from illustration to fiber sculpture and installation. How has that evolution shaped the intentions behind your practice?

Illustration first taught me to trust images instead of words, but the edges of the page still confined me. Working with fibers and installations opened things up: the work could breathe, age, and correct itself over time. Now I feel I’m building a condition rather than telling a complete story—I make a space where feeling happens on its own.

Time and decay are collaborators in your work. Could you share a story of a piece that continued to change after being exhibited?

Once, I made a faint trace on the floor using citrus powder. At first it looked clean, but during the show, people’s footsteps and the air conditioning scattered it, mixing it with dust. Eventually, the cleaning staff wiped it away as if it were dirt. I loved that—it was the piece finding its own way to disappear, becoming the quietest yet longest-lasting part of the exhibition.

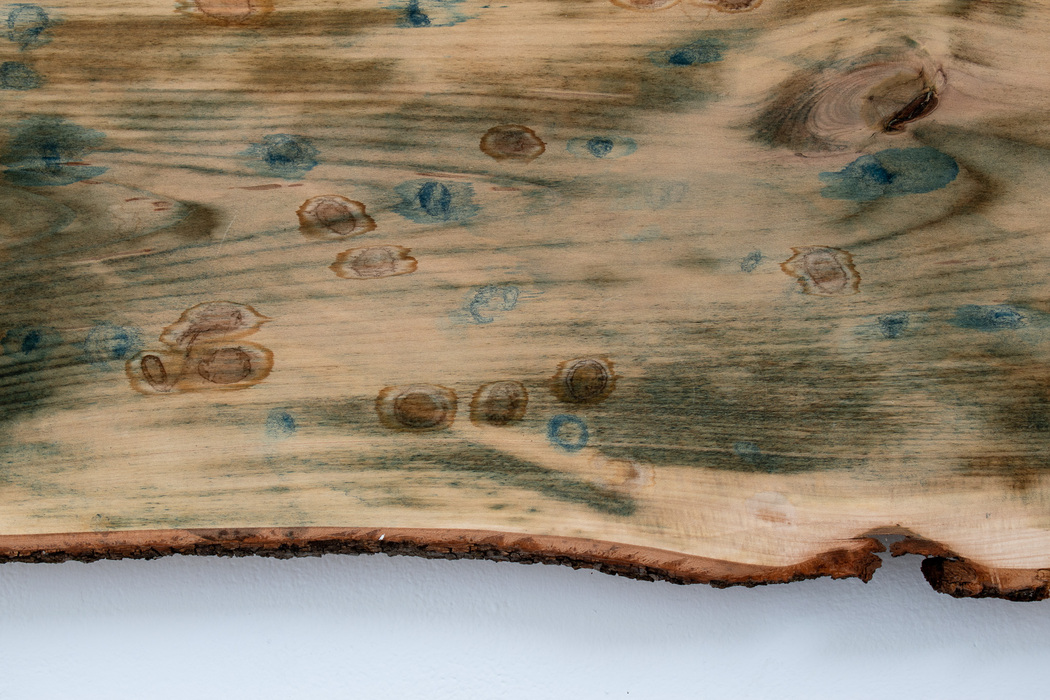

Yanqing Pan | Echoes of Drift | 2025

Yanqing Pan | Echoes of Drift | 2025

You mention listening to materiality rather than controlling it. What does that creative dialogue feel like in the studio?

I never start with an idea and then simply make a piece to match it. Instead, I stay with the material and pay attention to how it reacts—whether it resists, collapses, or slowly transforms on its own. It feels more like an ongoing negotiation than a plan. Sometimes what emerges surprises even me. The work grows out of this back-and-forth: my intentions meet the material’s limits, and in that space, something unexpected becomes possible.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.