Enzo Lauria

You describe your works as “theoretical objects” that reflect on the image itself. Could you elaborate on how this concept manifests in your painting process?

When I talk about “theoretical objects” and “metapainting”, I am referring to Victor Stoichita’s concept of “self-aware images”—paintings that playfully reveal their own fictiveness. Painting thus becomes a field of visual experimentation in which art reflects on itself, its potential, its limits, its truth, and its nothingness.

According to the famous metaphor used by Leon Battista Alberti in De pictura (1435), for a long time painters have conceived painting as an “open window” through which a viewer perceives the world. Yet at times—whether intentionally or not—artists have revealed the fictiveness of this belief. Take, for example, Guido Reni’s Landscape with Country Dance (1605), in which he painted two flies resting on the surface of the painting, almost as if he wished to tempt the viewer to chase them away with their hand. In this way, the true subject of the painting is not the landscape itself, but rather the painting as a flat surface on which two flies rest. In some of my works, the “Albertian window” is closed, revealing a pane of glass that is fogged up or crossed by drops of water. Thus, the true subject of these paintings is not the blurred forms depicted beyond the glass, but the painting itself as a flat, glass-like surface. These are examples of “theoretical objects” that reflect on painting’s inherent flatness.

Furthermore, my paintings often stage the making of the painting itself, thereby constituting themselves as “theoretical objects” that reflect on the illusory nature of representation.

How has your academic background in the History of Art and Gestalt Psychology influenced your artistic vision and the way you structure your compositions?

Gestalt Psychology is founded on the observation that we do not comprehend our world as an assemblage of disparate elements, but as a pattern of meaningful forms. In this way, Lacanian theory incorporates elements of Gestalt Psychology, particularly in the “ah-ha experience” that characterizes the mirror stage, where the infant grasps the connection between the image and its own existence. Following Lacan’s research on vision, the viewer—when looking at paintings or images—may sometimes experience the uncanny feeling of being gazed at by the objects of their own gaze. This moment represents an unexpected disruption of the viewer’s everyday perceptual experience and evokes a strong emotional response.

There are many accounts of this phenomenon. Jacques Lacan, for example, felt watched by the anamorphic skull depicted in Hans Holbein’s The Ambassadors. Bergotte—a fictional character in Marcel Proust’s In Search of Lost Time, maybe his alter ego—was fatally obsessed with a little patch of yellow wall he noticed in Jan Vermeer’s View of Delft. Georges Didi-Huberman was deeply captivated by the formless traces of colour he observed in Jan Vermeer’s The Lacemaker and in Beato Angelico’s frescoes at the San Marco Monastery in Florence. And the list goes on.

Like Lacan, Proust, Didi-Huberman, and many others, when I look at paintings, I love to analyze details that deeply capture my attention, even the most unlikely ones, such as cuts, erasures, craquelé, patinas, and other unpredictable elements that may affect the surface of artworks. Sometimes, I replicate them in my paintings. In this way, the vast catalogue of images offered by the History of Art has been an endless source of inspiration for my work. When I was a student at the Academy of Fine Arts in Urbino, my attention was captured by the powerful backgrounds in some of Goya’s paintings, especially the one in The Family of the Infante Don Luis. It was a stunning example of layered painting, where layers of green over red achieved a perfect chromatic balance. I have reproduced it countless times.

Enzo Lauria | The image and its double, the referent | 2024

Enzo Lauria | The image and its double, the referent | 2024

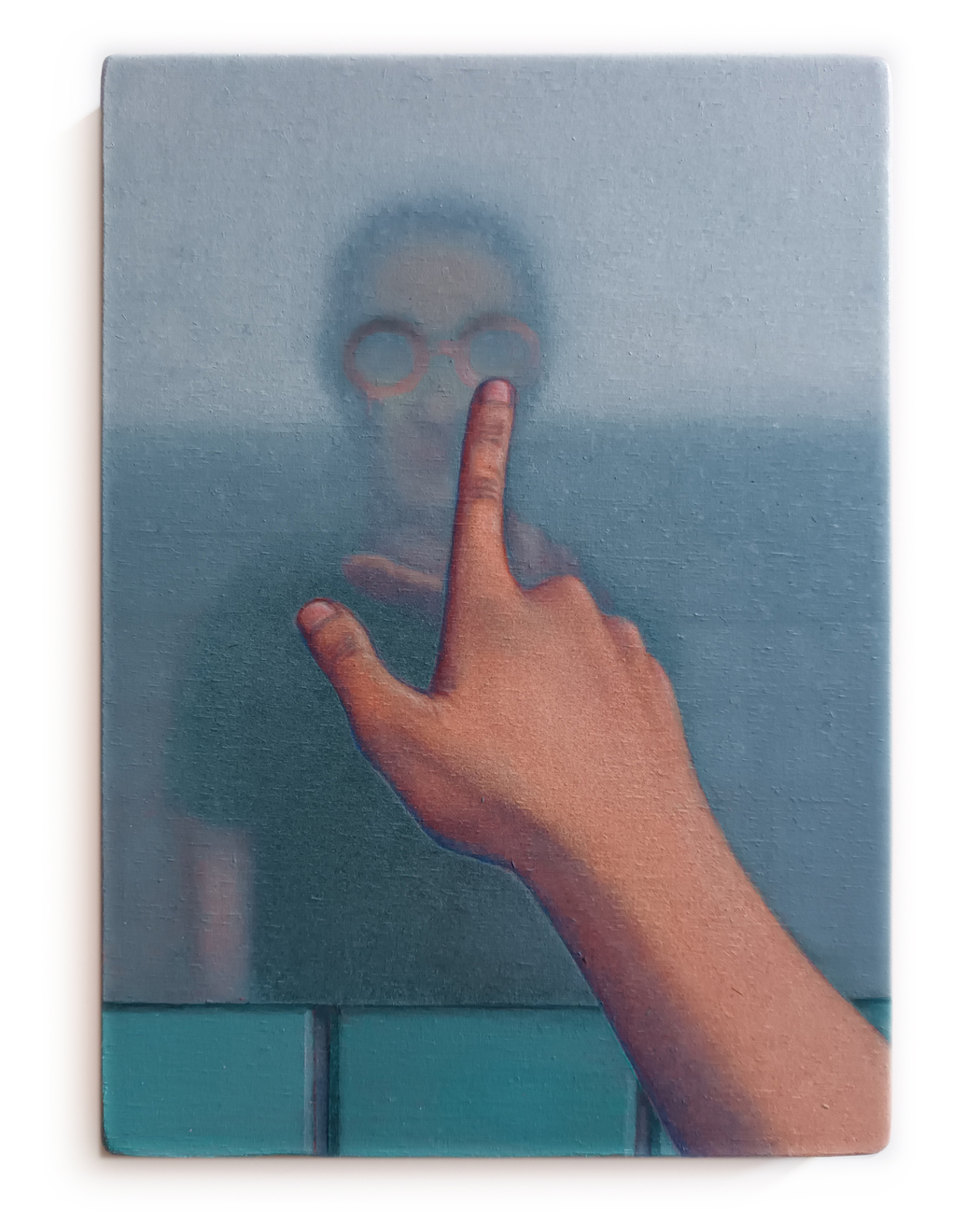

In several of your paintings, we see fingers “touching” or interacting with virtual interfaces. What does this gesture represent in the context of metapainting?

According to Victor Stoichita, the pictorial devices through which artists introduce their authorial self into the image and stage the making of the image itself form the foundation of a new poetics: the poetics of metapainting. In my paintings, deictic gestures introduce my authorial self into the image—indicating points of interest or performing meaningful actions—while the drawing hands stage the making of the image itself.

The blurring, condensation, or distortion of space in your paintings creates a feeling of ambiguity. What role does this visual flattening play in your concept of perception?

The feeling of ambiguity arises from painting’s enduring oscillation between flatness and depth, as seen in my painting The Image and Its Double, the Referent, which presents a real three-dimensional brushstroke alongside its representation through the chiaroscuro technique. At first glance, the viewer notices no difference between the two brushstrokes; both appear three-dimensional. However, when viewed from an oblique angle, the illusory nature of chiaroscuro becomes evident—its flatness is revealed.

The idea of art as an imitation of visual reality has dominated art history for centuries, and painters, working on flat surfaces, have devised various techniques to suggest depth: chiaroscuro, perspective, and more. However, when the surface of the painting is damaged—by cuts, erasures, craquelé, burns—or looks covered with dust, drops, condensation, etc., flatness may return stronger than before.

Flatness is always around the corner.

Do you consider your paintings to function as analog metaphors for digital experiences?

It’s something I have never thought about deeply enough. Anyway, in the digital age, interaction with images is no longer a prerogative of the eye; it also engages other senses, the touch above all. In this context, the cuts, burns and erasures that I sometimes introduce in my works may suggest a form of haptic interaction with the image.

Enzo Lauria | Self-portrait with glasses | 2023

Enzo Lauria | Self-portrait with glasses | 2023

How do you decide on the symbolic or compositional role of the hand in your paintings? Is it a surrogate for the viewer or a self-reflexive element?

It is my “Deus ex machina”, a device I use to resolve the plot of the painting; it tells the story.

By the way, I love the surreal images displayed in 16th and 17th century emblem books. They often depict giant disembodied hands engaged in an action to illustrate a “motto”. Sometimes they serve as a source of inspiration for my work.

Can you share more about the technical process behind creating the illusion of fogged glass or screen surfaces in your paintings?

The fogged glass depicted in my paintings is created using a thin, semi-transparent layer of grey oil paint.

Glazing is a technique that consists of applying a transparent layer of paint over another thoroughly dried layer. The upper and lower layers of paint mix optically, rather than physically, creating a unique stained-glass effect that cannot be achieved through direct mixing of paint.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.