Yixin Zhang

Year of birth: 1985.

Where do you live: Chengdu, China or San Jose, California.

Your education: National Academy of Chinese Theatre Arts.

Describe your art in three words: Observation, sociology, humanity.

Your discipline: Film & Theatre Production.

Website

What inspired you to create Mega Foundry, and what message do you hope to convey through this project?

A few years ago, I was living in Beijing, surrounded by artists and intellectuals, but I started to feel like I was stuck in a bubble. One day, I visited Yiwu for the first time, and it completely changed how I saw China. It wasn’t the skyscrapers or trendy galleries that defined the country—Yiwu showed me a different kind of reality—one driven by production, trade, and sheer human effort.

How has your experience in documentary filmmaking influenced the way you approached the visual narrative of Mega Foundry?

The observer is also a creator. I’ve always believed in letting visuals do the talking. The camera is like a quiet observer. People’s daily lives hold so much poetry if you look closely. For Mega Foundry, I leaned into that—capturing the hypnotic hum of machines, the repetitive motions of workers. There’s no dialogue, no storyline, not even a protagonist, yet the meaning unfolds through the visuals.

The film explores the relationship between humans and the objects they produce. How do you view this relationship evolving in the modern era of mass production and technological advancement?

It’s getting more complicated. The more things we make, the more we become part of the system. As technology advances, we’re increasingly defined by what we buy, what we wear, and what we consume.

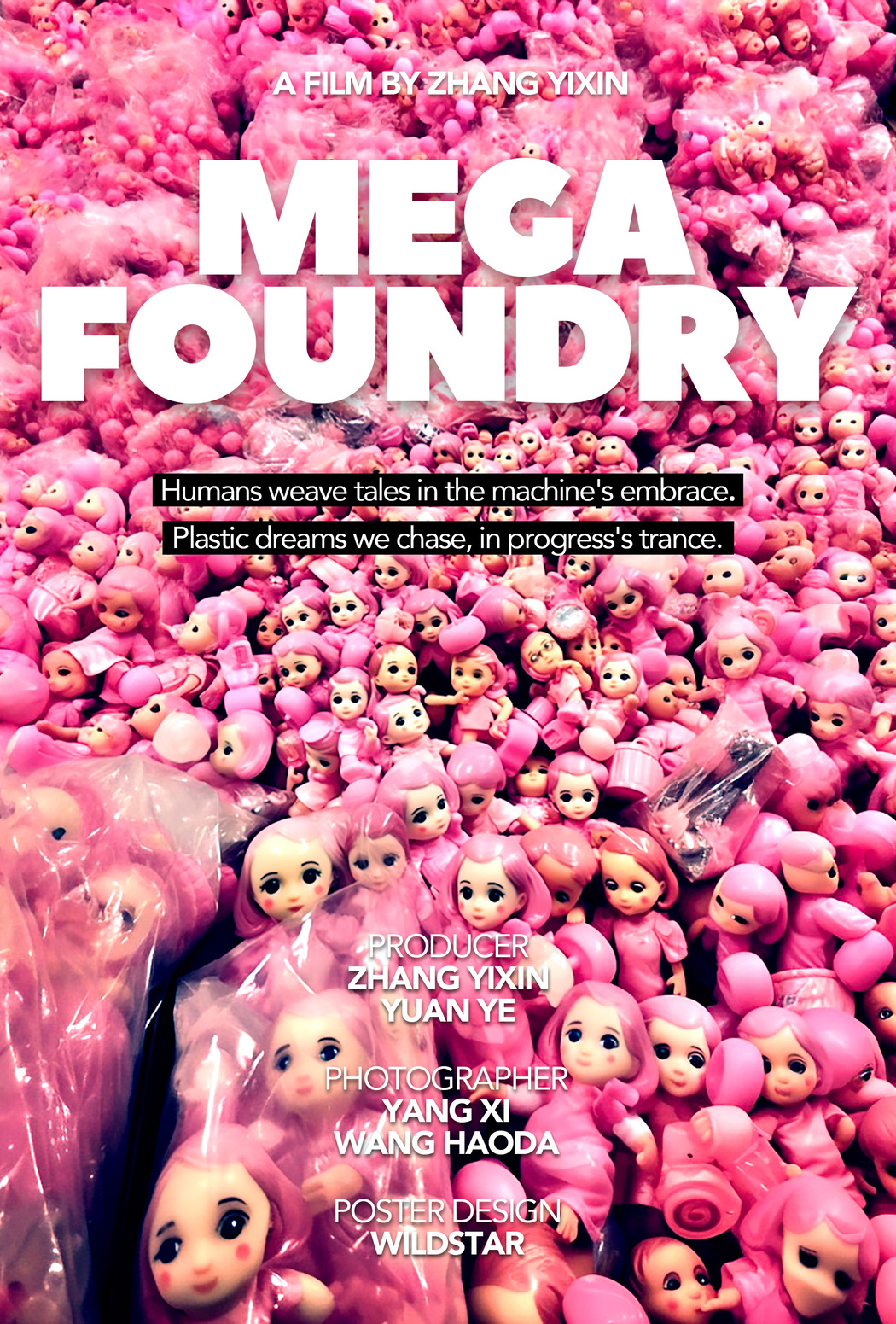

Can you elaborate on how the imagery of dolls and factory settings symbolizes human existence and materialism?

The dolls were one of my favorite parts to film. They’re like symbols of standardized beauty—flawless, identical, and endlessly replicated. In a way, we’re all part of this production process. In the past, machines were tools for humans; now, they’re shaping how we think, work, and even what we desire. AI, in particular, has accelerated the process of mass production, making it faster and more efficient. But the more efficient we get at making things, the more we seem to lose track of who we are in the process. People are becoming just another part of the machine—our time, our labor, and our desires are all products being processed and consumed.

What were some of the biggest challenges you faced while creating Mega Foundry, both technically and conceptually?

Technically, shooting in factories was tough. People in Yiwu are very busy, and they neither have the time nor the understanding for filming. I spent a lot of effort making friends locally. I needed so many locations and had to get filming permissions one by one. In the end, I had no choice but to shorten my original 40-minute film to just 10 minutes because many scenes I wanted to capture, like factories related to birth products and factories connected to death-related products, were inaccessible. And I ran out of money—from filming commercials—to continue. Conceptually, it was a challenge to avoid oversimplifying the story. I didn’t want to just say, “Factories are bad” or “Materialism is evil.” It’s more nuanced than that. One vendor joked that I should quit filmmaking and start selling products like him. The people I met in Yiwu have real pride in their work. It’s their livelihood, their identity. Balancing that complexity was probably the hardest part. I spent a lot of time with them, and they convinced me: films are meaningless, and no one cares. Especially for non-entertaining ones like this, there’s no market. I set the footage aside after a not very successful shoot. I was also working on a feature-length project called “Singing for Silence”. I filmed Mega Foundry in 2017. It wasn’t until 2024, when a curator friend encouraged me to submit it for an exhibition, that I finally finished it.

How do you balance dramatic storytelling with the documentary aspects of your filmmaking style?

I actually love creating stories—it’s where my heart lies. But somehow, documentary subjects keep finding me. These projects capture my attention and end up sharing a big part of my life and creative energy. Maybe that’s why I haven’t made a narrative film yet. With Mega Foundry, it all started with the overwhelming visual impact of the landscapes in Yiwu. The endless factories, the piles of products—almost surreal. A non-narrative approach felt like the best way to express that. It wasn’t about telling a single story but about creating a sensory experience, letting the visuals and sounds speak for themselves.

What role do you believe filmmakers play in addressing social issues and sparking meaningful conversations through art?

Film is one of the most accessible forms of art—it reaches people from all walks of life. It takes complex social issues and translates them into something emotional and relatable. A film doesn’t have to lecture but open doors—create space for people to see the world through a different lens and start conversations they might not have otherwise. It’s not about providing answers but sparking curiosity and connection.

What’s next for you after Mega Foundry? Are you exploring similar themes in your future projects?

Besides the documentary I’m about to finish, “Singing for Silence”, which tells the story of hearing-impaired children and their relationship with music, I’m interested in continuing to explore how people and systems intersect. AI is speeding up the world’s shift to being system-driven. How will it develop?

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.