Melanie D Berardicelli

Year of birth: 1995

Where do you live: Long Island

Your education: I received a Bachelor of Fine Arts degree in Painting and Drawing from SUNY New Paltz in 2017, and a Master of Fine Arts degree in Painting at the New York Academy of Art in 2021.

Describe your art in three words: Religious, Ornate, Skeletal

Your discipline: Painting, Drawing, Sculpture, Anatomy

Website | Instagram

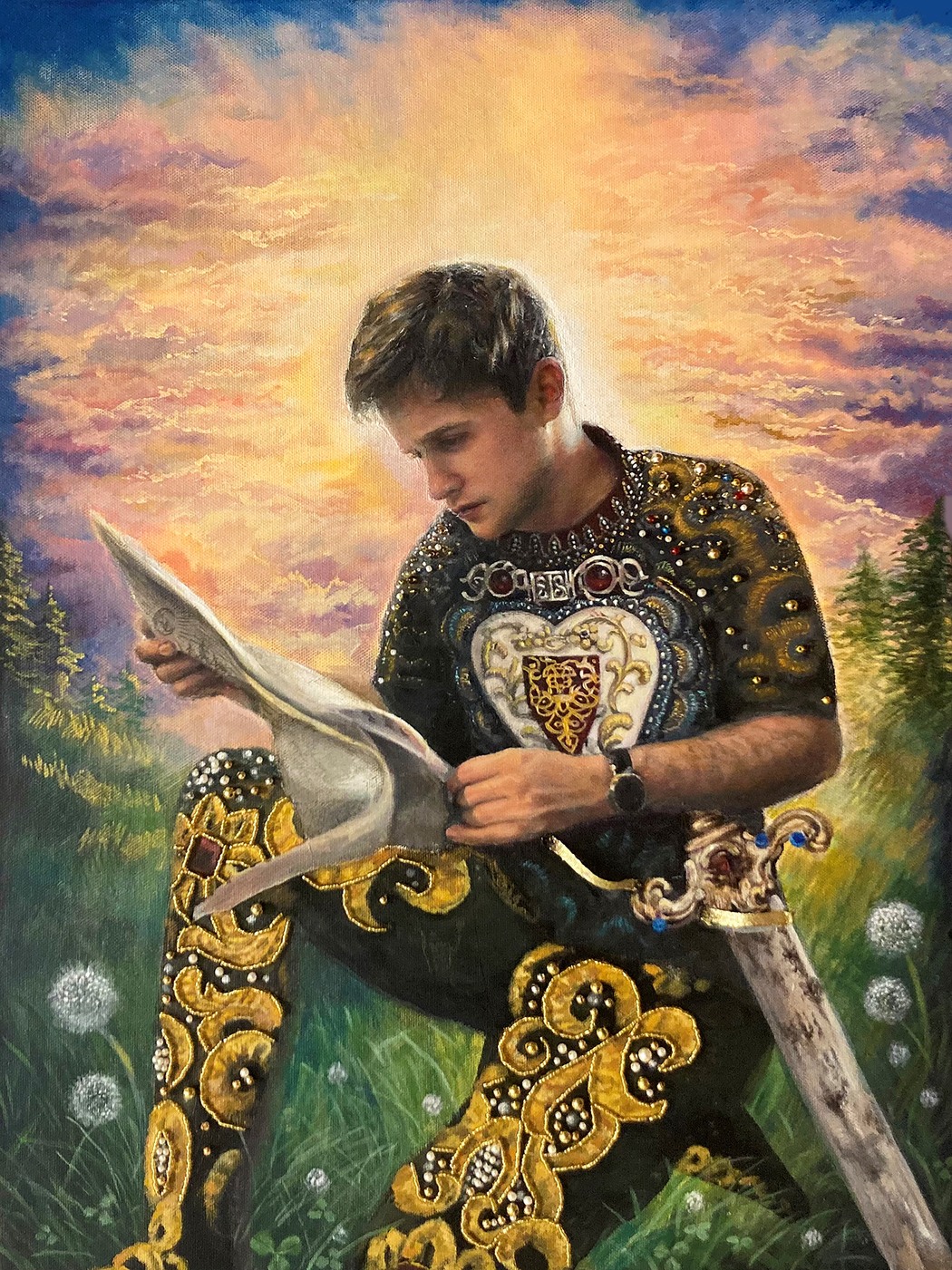

Berardicelli Melanie, From The Heavens Looking Down

Berardicelli Melanie, From The Heavens Looking Down

Can you share more about how the loss of your brother in 2020 influenced your artistic practice and your exploration of faith and grief through your art?

In November 2020 I had lost my older brother, Christopher Berardicelli, to brain cancer. He was only 34 years old. Being nine years older than me, he was my role model. I looked up to him all my life- both in the literal and figurative sense. As you can imagine, I was absolutely gutted; how could someone so kind and pure of heart die such a horrible death at a young age? What was I going to do without my big brother? Nothing seemed to make sense to me, and I felt completely lost. Prior to my brother’s passing, I had painted and animated scenes of different interior scenes at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and before that, figures surrounded by vibrant florals. It felt ingenuine to continue with either theme; I needed to address my grief head-on rather than hide it behind such cheery imagery. Thus, I was searching for something religious that focused a bit more on the human aspects of faith and death. During that time, it was incredibly hard for me to talk about my brother’s death, or to even let my peers know he had passed; but, where words fail me, art speaks.

What drew you to the Roman Martyr Catacomb Saints and Paul Koudounaris’s work? How did they shape your creative direction?

What didn’t draw me in? The Roman Martyr Catacomb Saints were a perfect blend of my love for the ornate, my faith, anatomy, painting, sculpting, and sewing. It was everything I had been looking for! Being a student of the New York Academy of Art at the time, I was- and still am- deeply intrigued by anatomy. In my personal taste, more is more is more. I spent hours poring over Paul Koudounaris’s book, admiring the shining, glittering, glowing gems, jewels, golds, and intricate embroidery. The sheer level of detail is utterly mesmerizing, and it was a literal investigation of the “riches of heaven.” I love intricate detail work in my paintings; I’m known for always having my beloved 20/0 Princeton Spotter Brush handy for the smallest of marks. It felt like destiny to paint these pearls, rubies, and brocade costumes. This inspiration has pushed my technical skill and attention to detail, as well as my bravery in confronting imagery that some might find intimidating or macabre.

Berardicelli Melanie, Copy of Saint Anny

Berardicelli Melanie, Copy of Saint Anny

Your art combines sculpture, painting, embroidery, and beading. How do these mediums interact in your work to express themes of devotion and memory?

The nuns of the German-speaking countries who received the remains of believed Christian Martyrs had spent years painstakingly hand-sewing and bejeweling ornate outfits to adorn the skeletons. Often, these nuns, as well as patrons of the church, would give up their own jewelry for these saints. This really struck a chord with me; if you truly believed you were tasked with the job of clothing a saint, wouldn’t you do the same? Thus, to properly honor the tireless dedication of these nuns, I hand-sew glass beads and gems into both painted canvas and original sewn outfits for sculpture. It’s a time-consuming process, but also a meditative one. I actually gave up a pair of my own earrings for the eyes of my piece, “Katakombenheiligen (Saint Severin).” In my painted works, I usually hand-sew gems located in the foreground, and allow the painted gems to rest back in space to push the senses of depth and illusion.

Can you describe your process of creating the resin-cast skeletal écorchés and their intricate costumes? How do you select materials and design each piece?

It’s a lengthy process, but I love good, hard work. The sculpture begins initially in plasteline. I’ll usually spend several months perfecting the skeleton, paying attention to details the viewer doesn’t necessarily have access to in the finished piece (vertebrae, ribs, the pelvis, etc.). Then comes the casting process. The plasteline can’t last as an independent sculpture for exhibition itself, as it never “dries” and is therefore always malleable, and by extension susceptible to being squished or ruined. Thus, I create a rubber mold using silicone; this layer captures all of the details I sculpted in the plasteline. A mother mold of epoxy dough is sculpted next on top of this silicone layer; I prefer epoxy over plaster as it’s lightweight and easier to sculpt shims with. Once all the layers have cured, the mother mold is cracked open, and the silicone layer is sliced along the shim line to release the original plasteline sculpture. The entire mold creates a perfect negative of the original, and allows the artist to pour any medium of their choosing into this shell to create a brand-new positive. Pouring is the tricky part; so much can go wrong in this next step. I take my time to ensure that the silicone and mother molds have aligned properly, pour the resin, and keep my fingers crossed that no air bubbles have accumulated. Carefully crack open the mold again (so as not to accidentally break the more fragile parts of the sculpture), clean up the seamlines, and voila! A brand-new skeletal sculpture! From here comes painting the resin surface to create a more illusionistic skeleton and sewing. I first design a pattern for the outfit on tracing paper, which I use to cut fabric. My designs are inspired by the pleated skirts, puffed sleeves, and ribcage-windows typical of the outfits that adorn the Roman Martyrs. Fabrics are selected for color and texture which best reflect such outfits. The pieces are sewn together and fitted to the skeleton. Then, I hand-sew glass beads, sequins, and gems into skirts and torso pieces; these beads and gems are similar to what I’d use to sew or create bracelets when I was a young girl. Final details, such as crowns or swords, are sculpted with Sculpey; a simple, yet honest material that can be baked in a toaster oven at home. From start to finish, a project such as this can take me six months.

Berardicelli Melanie, The Time Traveler

Berardicelli Melanie, The Time Traveler

You reimagine the identities of saints in your work. How do you approach giving these figures a new narrative inspired by the heroic people in your own life?

I usually consider the nature of each skeletal saint I observe in my studies. For example, in my painting, “Sir Stephen,” I decided to paint my long-time friend, Stephen Schmitt, who has always been dear to me. I can’t help but paint from the heart. In the Church of St. Verena there are a pair of Roman Martyrs, a male and a female, who have been displayed as a divine couple. Their design is a little more unique than most other Roman Martyrs; rather than a ribcage window, they bear large matching hearts on their chests. How touching! I always consider the personality of my subjects; Stephen is depicted with a sword, as he is a defender, and looks to the heavens in deep thought, true to his character. A faint golden light surrounds his head; this hero is enlightened.

Other times, I consider the name of my friend and the name of the saint. When the Roman Martyr Catacomb Saints were first sent to Germany, there was no way to tell what their original names were; thus, the church would christen them after names of saints in the bible, or simply called them “Saint Incognito.” In the same manner, I depict John as a Saint John, or Severin as a Saint Severinus, or Stephen as a Saint Stephen.

How does your background in anatomy and your work with Audrey Flack influence your artistic vision and technical approach?

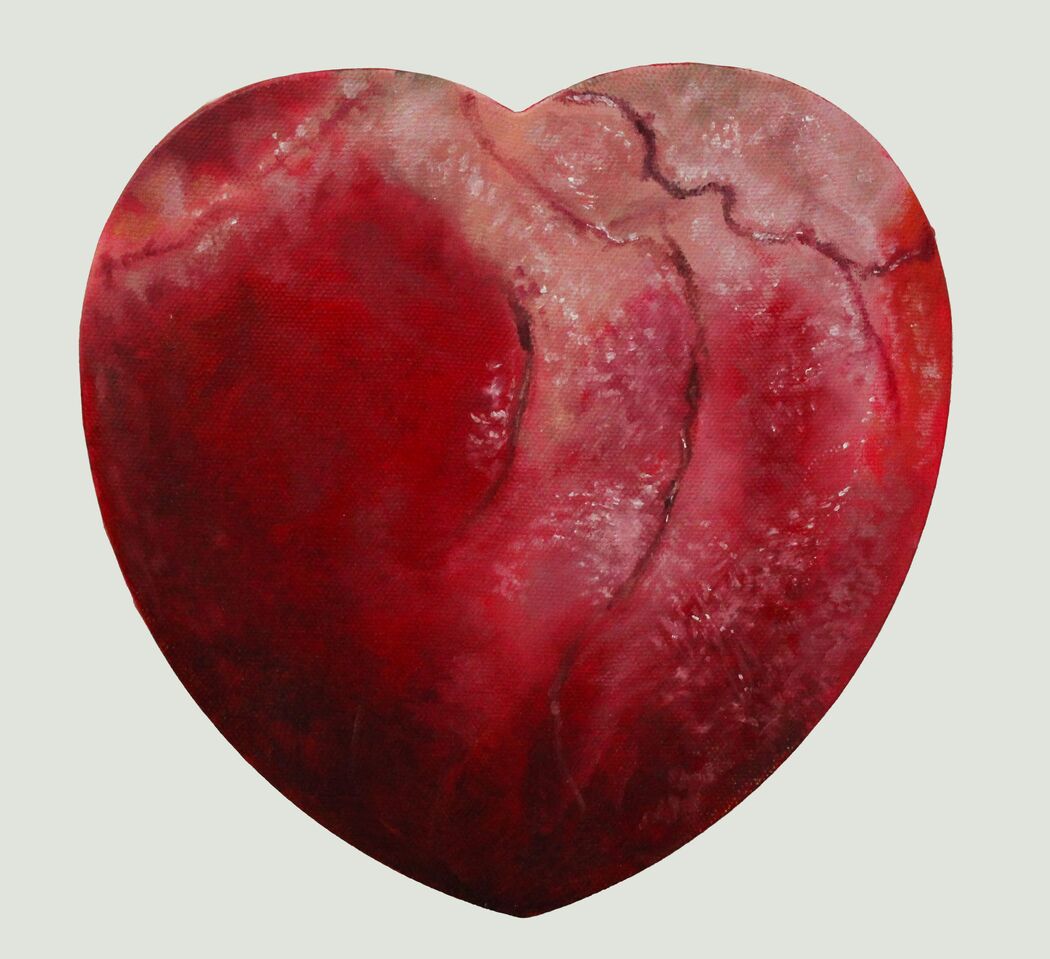

This is an interesting question! Not many people know this, but I had painted many of Audrey Flack’s Post-Pop Baroque paintings before she had passed. Audrey had hired me as a studio assistant after I had graduated from the New York Academy of Art in May 2021; she had been my Painting IV professor and was looking for someone who could help her with a new project. At the time, Audrey had just turned 90 and was unable to do much work on her paintings due to her health. Thus, I became Audrey’s “hands,” painting what she directed me to do. The very first piece I began painting independently for her was “Self Portrait with a Flaming Heart.” She, like me, was meditating on the concepts of religion, hope, the grieving heart, and death. The last piece I helped with was “A Brush With Destiny,” which at the time we simply called “Queen Elizabeth” in the studio. This was a fun project for me! I spent the summer of 2022 painting over 300 pearls and sculpting the brocade for that piece; Audrey and her studio manager, Severin Delfs, had nicknamed me “pearl girl.” For all of Audrey’s pieces, I was painting acrylic on canvas. I had to learn how to be efficient in handling this medium due to its quick dry time- as well as Audrey’s expectations for quick turnover! Thus, I became a lot more efficient in my own work. A lot of my pieces are oil and acrylic on gessoed paper or canvas; I begin my portraits in the same manner I did for Audrey with acrylics but push them further with my background in oils to create more illusionistic flesh tones, highlights, and juicier color. I also collage my compositional elements similarly to how Severin and I would when mapping out a new piece for Audrey; a gem here, a sword there, all, of course, inspired by the actual outfits that adorned the Roman Martyrs.

From 2021-2022, I was simultaneously assisting Cynthia Eardley at the New York Academy of Art for her Structural Anatomy courses (this is before I became an MFA Structural Anatomy professor myself in Fall 2023). For this class, students sculpt a 24” écorché- meaning “flayed flesh”- to study both bone and muscle anatomy. We start off with basic geometric shapes for the head, ribcage, and pelvis to capture accurate proportions prior to delving into the finer details and nuances of each bone. When I draw the skeleton, I think like a sculptor, focusing more on planes and volumes before line weight, light value, and likeness. Once you have a solid foundation, that’s when you can go wild with details; a suture line here, a tubercle there. Teeth are my absolute favorite to paint and sculpt. Every skull is different, and equally exciting for me to study through my work. Thus, the catacombs are an anatomist’s treasure trove, as there is always something new to discover!

Berardicelli Melanie, The Hermit

Berardicelli Melanie, The Hermit

What role does your experience as an educator play in your art practice? Do teaching and creating intersect for you in meaningful ways?

Often my demonstrations I create for my MFA, CFA, CE, and SURP students lead to interesting experiments in my own work. In summer 2023, I taught a few portrait sculpture classes through the New York Academy of Art’s Summer Undergraduate Residency Program. In any class I teach, I like to balance rigorous technique with creative expression; what’s the point of art if you’re not enjoying it and letting your own voice shine through? For my demo, I decided to try out a theory I had of reversing the forensic process; could I strategically remove clay to the depth of standard tissue markers to reveal the shape of the skull underneath a face? This led to the creation of my sculpture, “Saint John.” Other pieces of mine- “Katakombenheiligen (Saint Severin),” “Skull Reliquary No. 1,” “The Time Traveler”-were created initially to serve as class demonstrations. New discoveries I make in my demos always influence the development of my personal work, and vice versa.

Berardicelli Melanie, Heart of Hearts

Berardicelli Melanie, Heart of Hearts

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.