AvRaam Cohen

Year of birth: 1968.

Where do you live: New York.

Your education: Master’s in Industrial Design.

Describe your art in three words: Light, Shadow, Color.

Your discipline: Sculpting by casting.

Website | Instagram

Your work often integrates industrial design with artistic expression. How do you balance these two disciplines in your sculptures?

Industrial design, in my mind, is the intersection of engineering and art, where creativity meets functionality. It blends technical precision with aesthetic vision to develop products that are not only efficient and practical but also visually appealing and user-friendly. From an engineering perspective, industrial design involves understanding materials, manufacturing processes, and technical requirements to create products that perform effectively and meet safety and usability standards. On the artistic side, industrial design emphasizes form, style, and the emotional connection between the product and the user. Designers consider factors such as color, texture, ergonomics, and cultural relevance to shape products that resonate with users on an emotional level. This fusion of art and engineering is what enables me as an industrial designer to create innovative solutions that enhance the quality of everyday life, whether it’s through designing a sleek consumer product, ergonomic furniture, or environmentally conscious packaging. When it comes to my sculptures, there’s naturally a much stronger focus on the artistic aspect, as function isn’t the main priority. However, I still draw heavily on my industrial design skills. I use them to figure out how to bring my vision to life: deciding on the right tools, selecting materials that enhance the message, and ensuring that the piece will physically work, whether it’s standing, hanging, or incorporating a specific interaction with light or space. I also enjoy pushing engineering tools to be repurposed in unexpected ways for artistic creation. This approach not only broadens my palette of creative solutions but also infuses my art with the precision and inventiveness characteristic of industrial design.

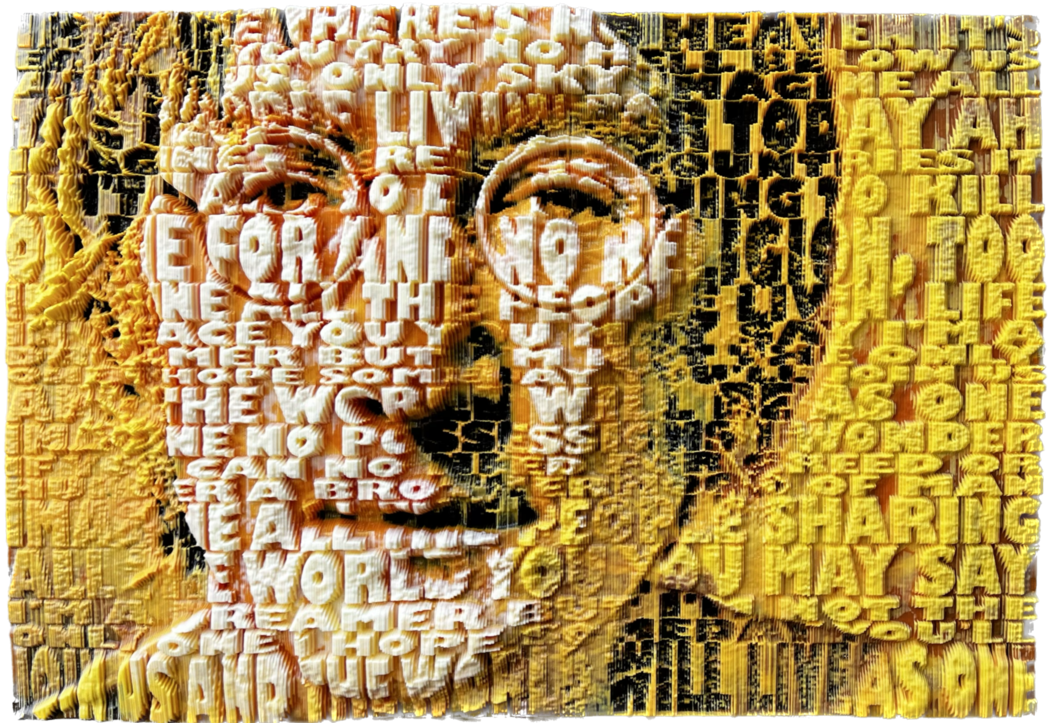

AvRaam Cohen | Imagine

AvRaam Cohen | Imagine

You mention being captivated by the power of color. How does color influence the emotional or conceptual impact of your pieces?

At first, I have to admit I was hesitant about using too much color in my artwork. Coming from an industrial design background, where color plays an important but very controlled role, I was used to a more restrained approach. In product design, color needs to be carefully selected—most products don’t use more than two or three colors because too much can make them feel cluttered or unfocused. When I started creating my first art pieces, I carried that same mindset, being somewhat shy about exploring color. But as I grew more confident in my artistic practice, I decided to temper my inner industrial designer and allow myself to experiment more freely with vivid colors and bold combinations. I quickly realized how profoundly color can influence the emotional or conceptual impact of a piece. It’s fascinating to see how the same form, when cast in a different color palette, can evoke entirely different feelings. For instance, a piece that feels energetic and vibrant in one set of colors might take on a more subdued or contemplative tone with another. Color has become a powerful tool for me to convey the mood or message I want to express.

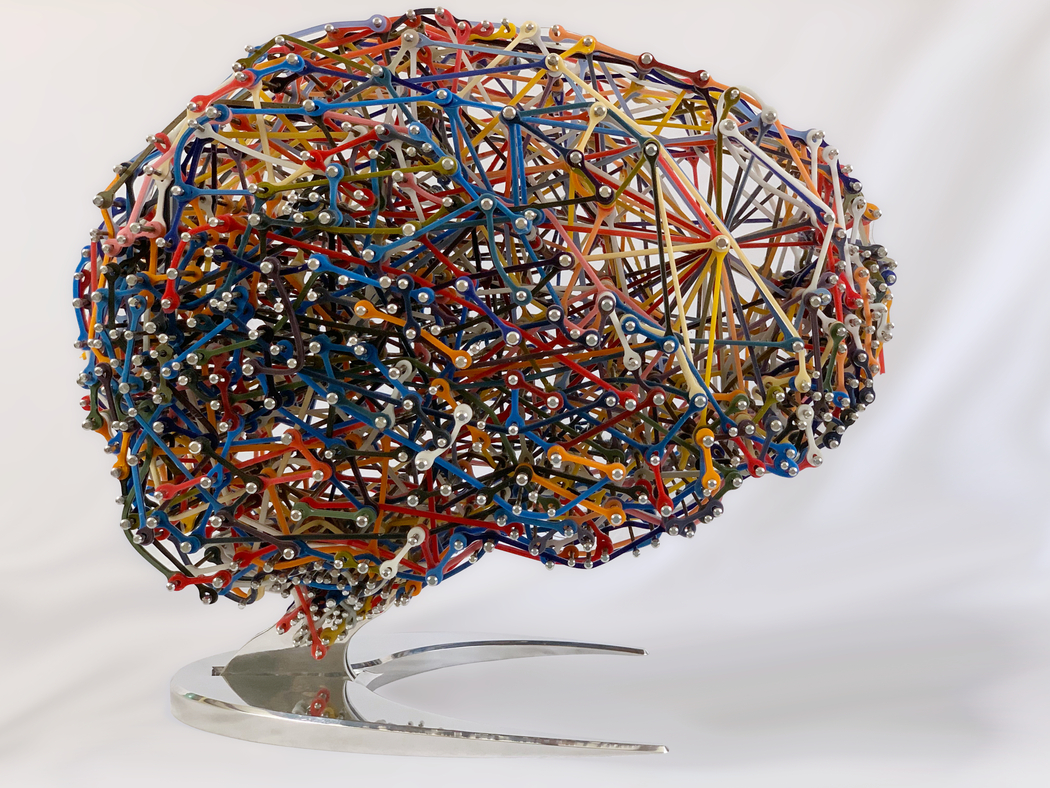

AvRaam Cohen | Brain in Time – Side

AvRaam Cohen | Brain in Time – Side

Your sculptures are highly dimensional and seem to play with light and shadow. Could you talk about your process in creating this depth and dimensionality?

Every piece I create begins with graphic design on a 2D platform. I start by setting up the composition, carefully placing design elements as needed to establish the visual foundation. Photo editing programs play a critical role at this stage, allowing me to manipulate the initial design and achieve the first step toward my vision. Depending on whether the piece will be a freestanding sculpture or a wall-mounted work, I then transition into a more technical phase. This involves using up to five or six different programs, many of which are traditionally used for engineering or CAD purposes. These tools help me transform the 2D design into a topographic solid representation, where highlights and bright colors are extended outward, while shadows and darker tones are recessed. It’s not a true 3D representation of the subject, but rather an artistic pixelation of light and shadow, almost like creating a landscape of contrast that plays with depth. Once the digital design is complete, I move into the physical creation process. Here, I utilize a range of tools, from laser cutting to coping saws, depending on the material and form. The most important aspect of this stage is that I handcraft each piece—at no point in this process do I rely on 3D printing. This hands-on approach allows me to maintain a closer connection to the work, ensuring that the final result reflects the texture, depth, and interplay of light and shadow I originally envisioned.

You have a long history in product development. How has your experience in this field shaped your approach to sculpture?

My experience in product development has significantly shaped how I approach sculpture. In product design, there’s a deep focus on problem-solving, functionality, and precision elements that have become second nature to me. This technical mindset has influenced my artistic process, especially in terms of how I think about structure, materials, and the way things are made. When I approach a sculpture, I draw on the same principles of design and engineering that I use in product development. I think about the form not just as an aesthetic object but also in terms of its construction, how it will hold up, what materials are best suited to achieve the desired effect, and how different methods of fabrication will impact the final result. The precision required in product design carries over into my artwork, where I often employ CAD tools and engineering software to help visualize and develop the piece before it’s physically created. However, in sculpture, I get to break free from the constraints of functionality that are always a priority in product design. I can experiment with form for its own sake, playing with shapes, light, shadow, and texture in ways that don’t have to adhere to the limitations of manufacturing or usability. Yet, my background always provides a strong foundation, allowing me to explore more complex forms while ensuring they are structurally sound. In short, my history in product development provides me with the tools and discipline for precision, while sculpture gives me the freedom to explore creativity in a more abstract, expressive way.

AvRaam Cohen | The King

AvRaam Cohen | The King

What materials or techniques do you find most fascinating when creating your sculptures, and how do they enhance the overall meaning of the piece?

I find exploring new materials fascinating because each one can profoundly influence the final outcome of a piece. Material selection is critical and, in some cases, is the primary way I convey the meaning behind the work. The texture, flexibility, and durability of a material can enhance or transform the message I want to express. For example, in my piece Brain in Time, the material choice was essential to conveying the concept. This sculpture was inspired by my father’s battle with Alzheimer’s disease, and I wanted to depict what I imagined was happening inside his brain during our final conversation. In my mind’s eye, I saw neurons connected by delicate, elastic rubber strings—some of them intact, while others were dried out and broken. These strings represented the fragile communication pathways in the brain. To bring this vision to life, I used metal threaded rods with aluminum caps to represent the neurons and colorful rubber strings to symbolize the lines of communication between them. The elasticity of the rubber reflects the healthy brain’s ability to form strong connections, while the dry, broken rubber bands illustrate the deterioration caused by Alzheimer’s. The materials allowed me to not only represent the brain visually but also evoke the physical fragility of the disease. Another example is my piece Excuses. For this sculpture, I used soft expanded foam to create a large wedge—a metaphor for how excuses function in our lives. Excuses are mechanisms we use to justify inaction, and by making the wedge out of soft foam, I rendered it as ineffective as an excuse itself. The choice of foam, which looks substantial but is physically weak, reinforces the concept that excuses seem like valid reasons but ultimately hold no weight or power. In both cases, the materials were as integral to the meaning of the work as the form itself, allowing me to express complex ideas in a tangible way.

AvRaam Cohen | Excuses | 2018

AvRaam Cohen | Excuses | 2018

In your artist statement, you mention drawing inspiration from both the craftsmanship of others and nature. Can you elaborate on how these influences manifest in your work?

For me, the ability to sculpt delicate, intricate shapes from a solid block of marble or granite by hand without the use of power tools is the ultimate expression of craftsmanship and talent. I have great admiration for those who can create such timeless masterpieces, as it requires both precision and an intimate connection with the material. Although I don’t possess the skill to work with marble or granite in this traditional sense, I often find myself inspired by these artisans and their work. In some of my pieces, I create my own interpretation of small portions of these monumental sculptures, using my own techniques and materials to express my admiration. It’s my way of paying homage to the craftsmanship that has always fascinated me, while also making it into something uniquely my own. Nature is another significant influence in my work. The organic forms, patterns, and structures found in nature often guide my designs. I aim to capture some of that organic complexity, blending it with the structured precision that comes from my background in industrial design. In both cases, whether drawing from human craftsmanship or the natural world, I try to translate these influences into something that feels personal and reflective of my artistic vision. They provide me with a sense of direction, but I always interpret them through the lens of my own techniques and concepts.

AvRaam Cohen | The Pipe 4×4

AvRaam Cohen | The Pipe 4×4

Many of your sculptures reinterpret 2D images into 3D forms. How do you select the images you work from, and what draws you to them?

The first step in selecting the images I work from is a simple admiration for the subject matter. I’m drawn to figures, concepts, or objects that resonate with me on a deeper level—whether because of their cultural significance, personal relevance, or the emotional response they evoke. Once I have an idea in mind, I search for an image that best captures the essence of the subject. From there, I manipulate the image to fit my vision, allowing it to evolve into something that speaks to both the original subject and the new context I’m placing it in. For example, in my piece Imagine That…, I wanted to create a representation of John Lennon using his own lyrics. The combination of the sourced image with superimposed text allowed me to form a three-dimensional face made entirely out of his words, which felt like a fitting tribute to someone who expressed so much through his music. The choice of lyrics as the medium became an integral part of the overall concept, emphasizing Lennon’s impact not just as an image but as a voice. Another example is my piece The Pipe, which depicts Albert Einstein smoking a pipe. Once I had sourced the image of Einstein, I began manipulating it to align with the vision I had in mind. I added a chalkboard full of equations in the background, paying homage to the intellectual brilliance of the man. The juxtaposition of Einstein’s relaxed posture with the complex mathematical equations serves as a reminder of his genius, both approachable and awe-inspiring. In both cases, what draws me to these images is not just their visual qualities but the stories, ideas, and emotions they represent. By transforming these 2D images into 3D forms, I aim to reinterpret them in ways that invite the viewer to engage with the subject on a deeper level.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.