Vriddhi Toolsidass

Where do you live: Los Angeles, California

Education: University of Southern California Bachelor of Arts Integrated Design, Business, and Technology

Describe your art in three words: Rooted, process-driven, embodied

Discipline: Textile-based installation, participatory art, and design research

Website | Instagram

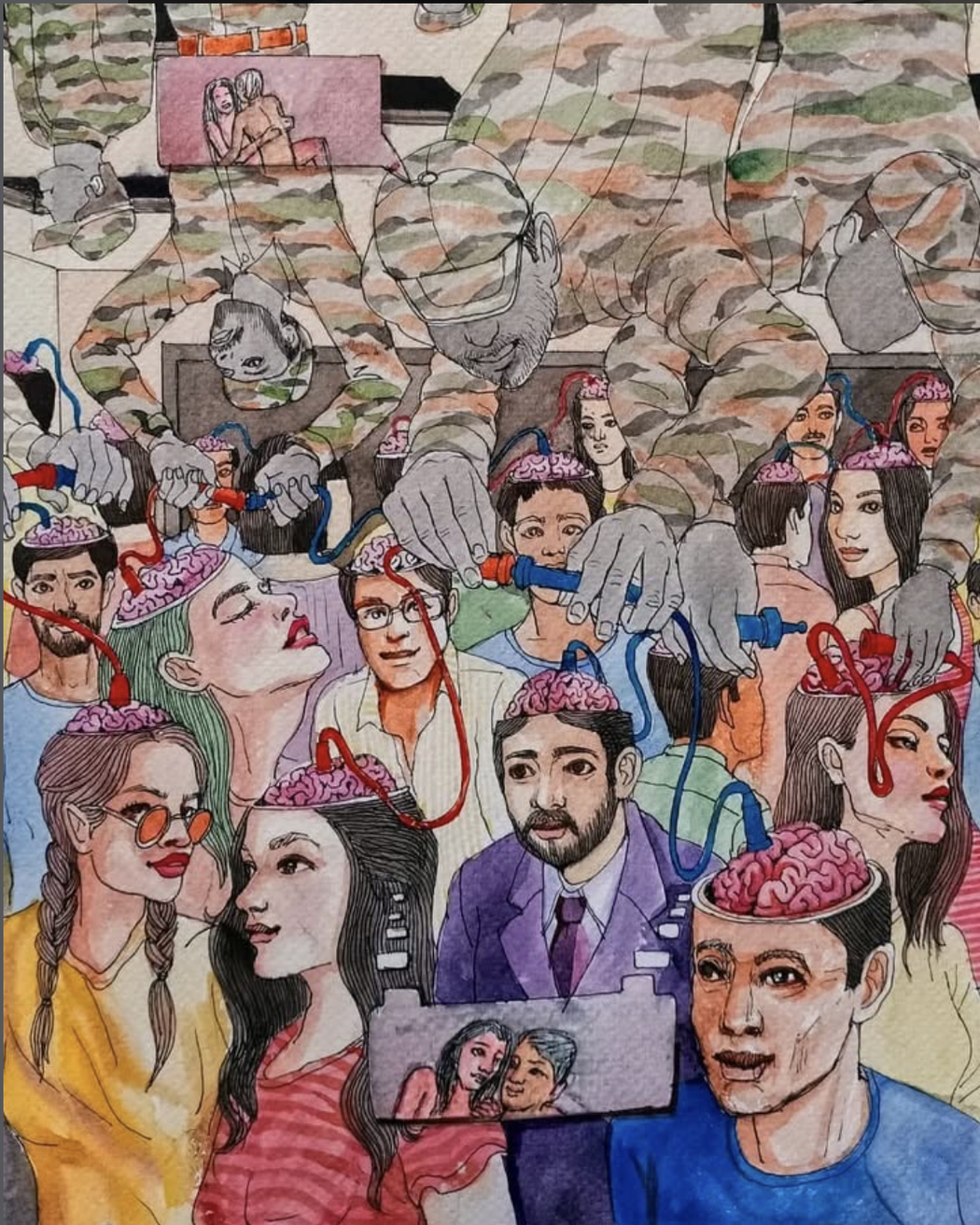

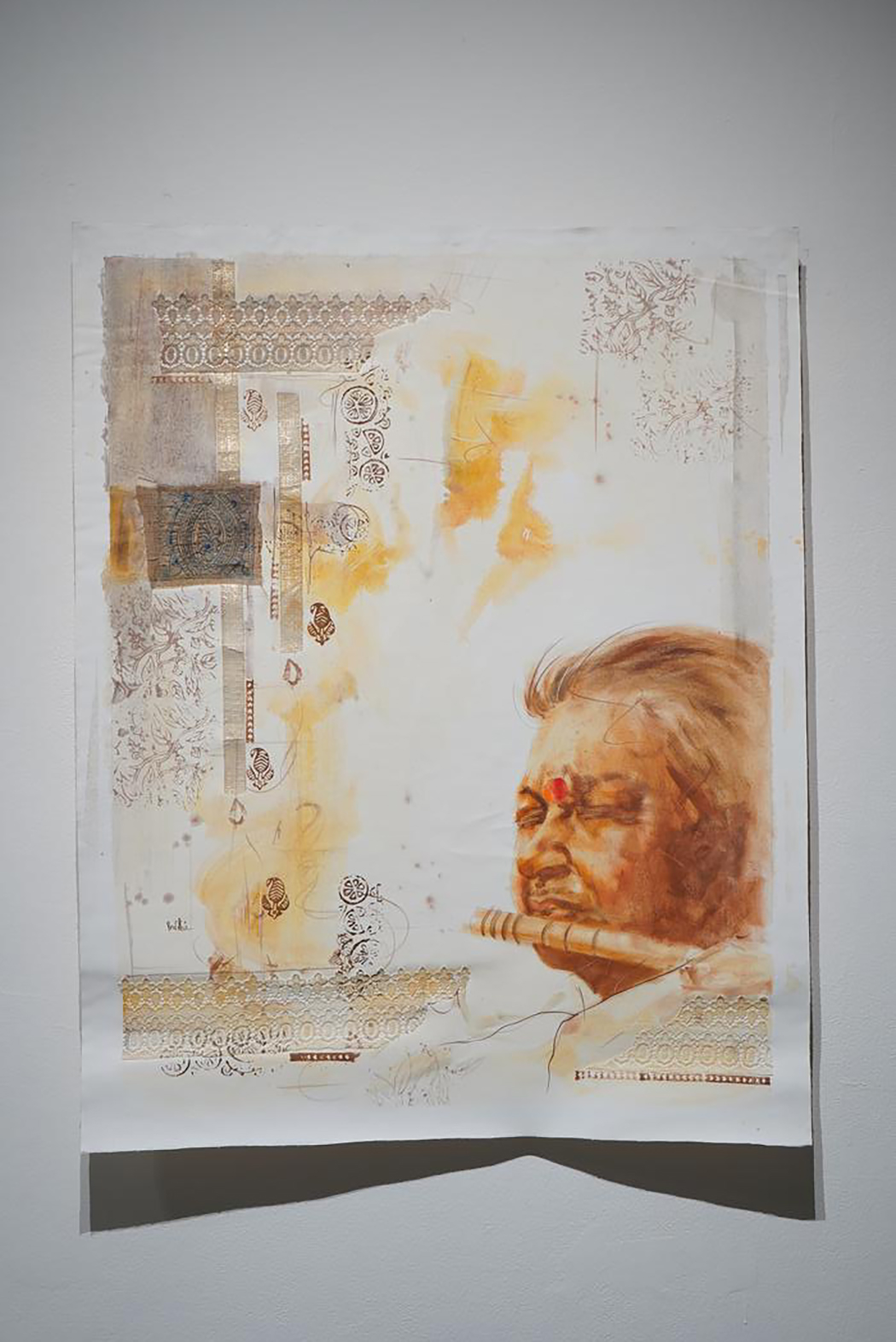

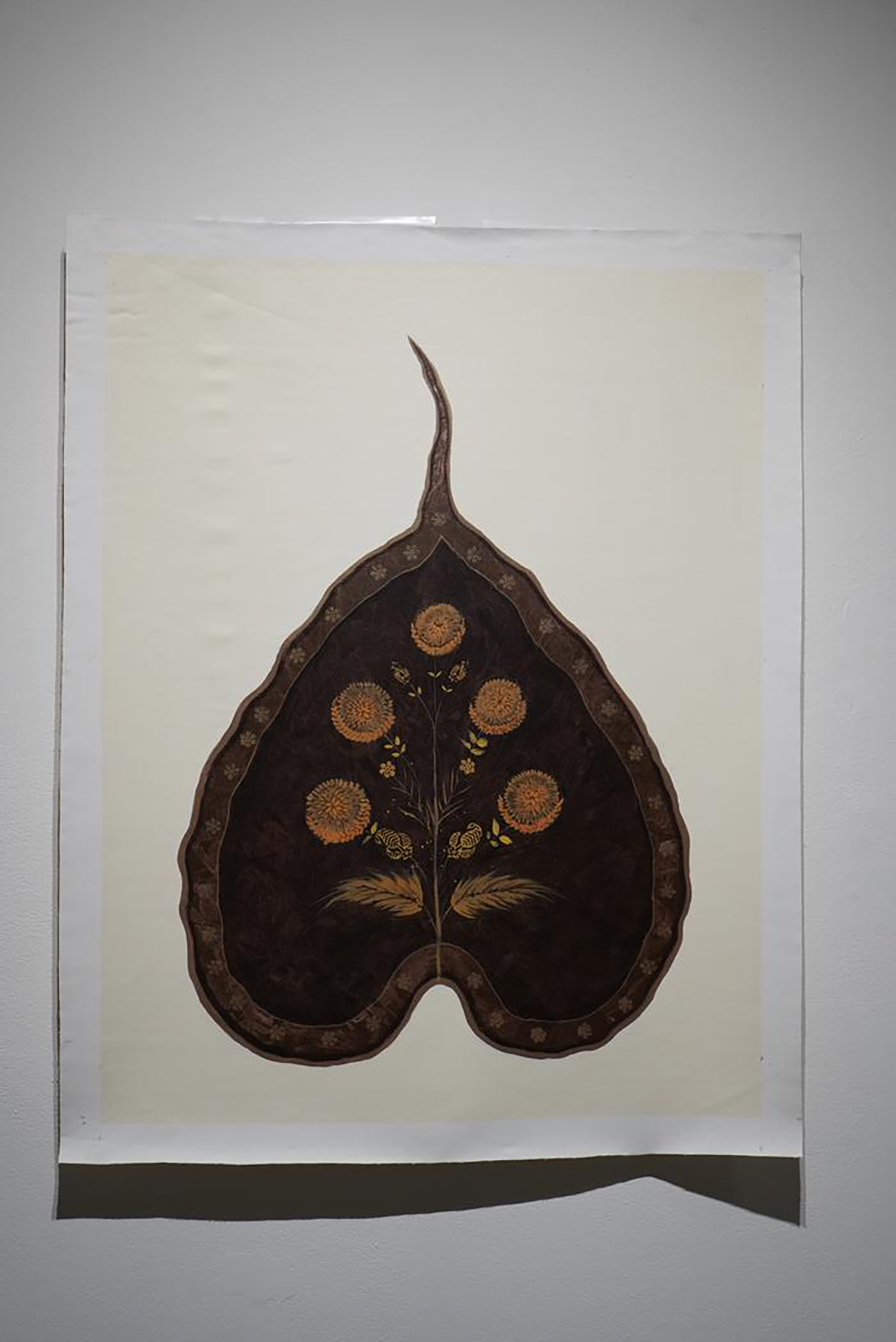

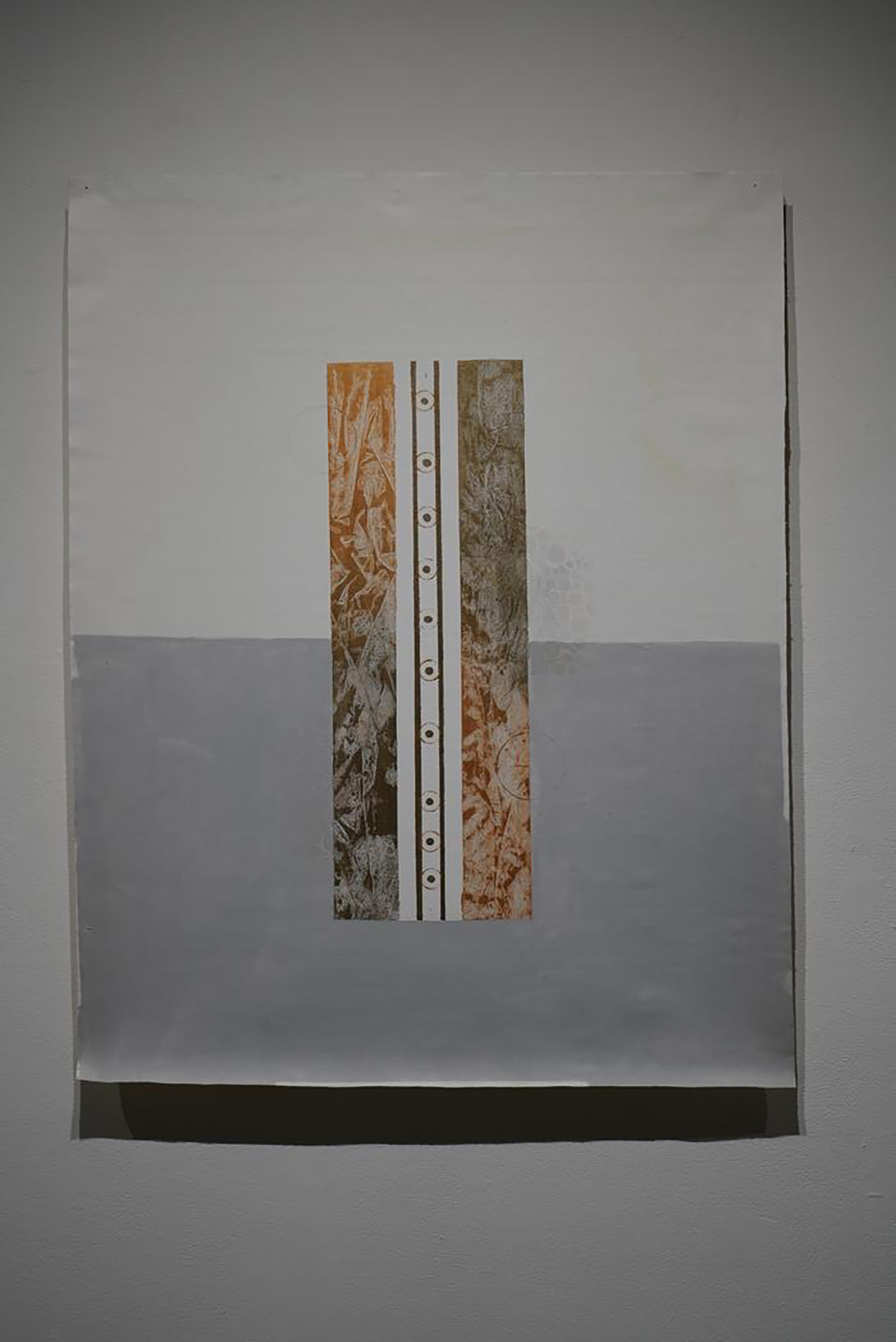

Vriddhi Toolsidass | Mission Mindconnect

Vriddhi Toolsidass | Mission Mindconnect

Your practice is shaped by migration between Hyderabad and Bahrain. How has this movement influenced your relationship with cultural memory and ritual?

Moving between Hyderabad and Bahrain meant that cultural practices were never entirely anchored to place. In Bahrain, many of the rituals that might have been public or communal in India became private and improvisational. They existed in kitchens, bedrooms, and storage cupboards rather than temples or community spaces. Because of this, cultural memory became something I learned through observation and repetition rather than instruction. I paid attention to how objects were handled, how fabric was folded and saved, and how certain materials were never discarded. This experience shaped my understanding of ritual as something sustained quietly over time. In my practice, I return to these small, persistent gestures. I am interested in how memory survives through care, through the continued use of materials, and through practices that adapt rather than disappear when displaced.

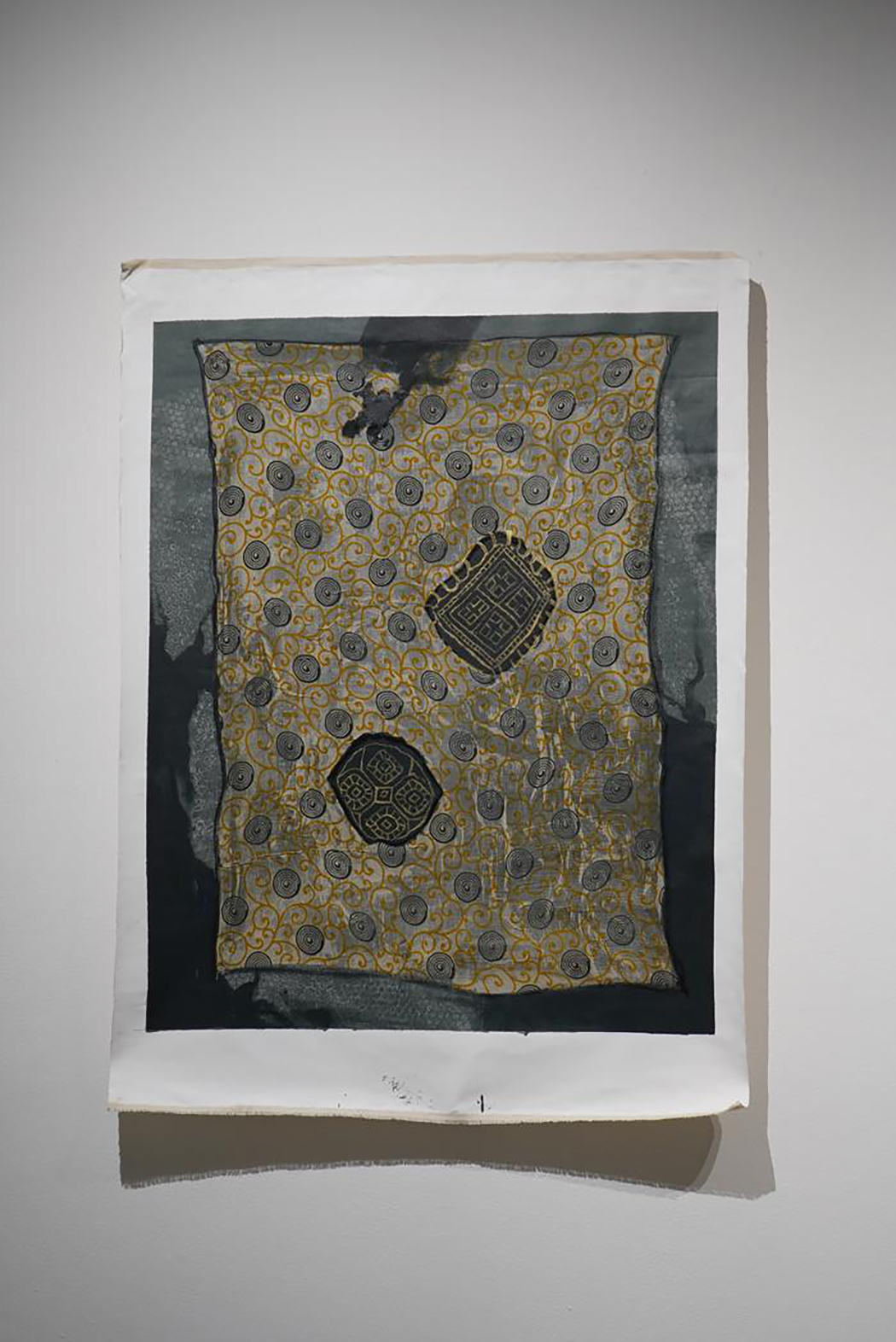

You describe textiles as operational vessels of labor, time, and devotion. When did you begin to see fabric as a system rather than a surface?

This shift happened when I began working closely with textiles that already had a life before me. Handling worn saris and hand-printed cloth made it impossible to ignore the layers of labor embedded in them. I became aware of how much time is required not just to make fabric, but to maintain it. Washing, drying, folding, storing, repairing, and repurposing are ongoing acts of care. Fabric organizes daily routines and carries physical traces of these interactions. Seeing this changed how I approached design. Cloth was no longer a neutral surface to decorate but a system that held history, labor, and devotion. I began to work in dialogue with the material, allowing its constraints and rhythms to guide the process rather than imposing a fixed visual outcome.

Can you explain your Ritual Systems Methodology? How does it guide your artistic decision-making across different media?

Ritual Systems Methodology is rooted in the idea that meaning emerges through repeated action over time. Instead of starting with a finished image or object, I begin with a set of gestures such as printing a block repeatedly, stitching by hand, or inviting others to participate in the making. These gestures become the structure of the work. The methodology helps me make decisions by asking how labor is distributed, how time is experienced, and how care is enacted throughout the process. When working across different media, I return to these same principles. Whether I am creating an installation, a textile, or a participatory workshop, the focus remains on accumulation, presence, and relational exchange. The work is shaped slowly through use and interaction rather than completion.

In The Slow Thread Collection, slowness is positioned as both an aesthetic and an ethical stance. Why is slowness a form of resistance today?

Slowness resists contemporary systems that equate value with speed, productivity, and scalability. In many design and production environments, speed becomes a way to disconnect objects from the labor and resources behind them. In The Slow Thread Collection, slowness keeps labor visible. Each piece requires sustained attention and cannot be rushed without altering its meaning. Slowness also resists disposability. It encourages viewers to spend time with the work and to consider the conditions under which it was made. Choosing to work slowly is an ethical decision. It prioritizes care, accountability, and respect for materials and people involved in the process. In this way, slowness becomes a refusal to participate in extractive systems of making.

Your textiles carry visible traces of the hand such as imperfections, repetitions, and variations. What do these marks communicate that industrial perfection cannot?

These marks communicate time, effort, and decision-making. They show where the body adjusted, where a gesture was repeated, and where fatigue or care shaped the outcome. Industrial perfection aims to erase these signs in favor of uniformity and control. In contrast, variation acknowledges the presence of the maker and the reality of human labor. For me, these traces are not mistakes but records of process. They allow the viewer to sense how the work unfolded and to recognize making as an ongoing, embodied act rather than a flawless result.

As someone trained in fine art, UI UX, and strategic design, how do you navigate the tension between human-centered design and systems of surveillance?

My training in UI UX and strategic design exposed me to how human-centered frameworks often rely on data collection and behavioral optimization. While these systems claim to prioritize users, they frequently reduce people to patterns and metrics. In my art practice, I intentionally work against this logic. I design experiences that cannot be easily measured or tracked. Participation is voluntary, outcomes are open-ended, and attention is not directed toward a single goal. This approach allows me to reclaim human-centeredness as something grounded in consent, presence, and care. The tension between these fields continues to shape my practice and keeps me questioning how power operates within designed systems.

How do you imagine viewers physically and emotionally engaging with your installations and what kind of awareness do you hope they leave with?

I imagine viewers engaging with my installations slowly and attentively. I want them to notice weight, texture, and proximity, and to become aware of how their bodies move through the space. Many of my works encourage touch or close observation, which creates a sense of intimacy and responsibility rather than distance or passive viewing. The installations are not meant to be consumed quickly. They ask for patience and presence.

Emotionally, I hope the work fosters care rather than spectacle. I want viewers to feel a quiet attentiveness toward the materials and the labor embedded within them. Textiles, film, and repeated gestures make visible the time, devotion, and human effort that are often hidden within everyday objects. Ideally, viewers leave with a heightened awareness of how materials carry histories of labor and belief, and how these histories are shaped by larger systems of production and circulation.

I also hope the work prompts viewers to reflect on their own pace and habits of looking. By slowing down their movement and attention, the installations create space to question how power operates within designed systems, including who is made visible, whose labor is overlooked, and how care can exist within structures that often prioritize efficiency and control.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.