Nguyen Minh Tri (Tonee)

Where you live: Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam

Your education: Undergrad at Fulbright University Vietnam

Describe your art in three words: Raw · simple · layered

Your discipline: Mixed media sculpture

You describe your works as “never fully completed.” What does the idea of incompleteness mean to you personally and artistically?

I tend to think of artworks as living beings, forever evolving and changing, either in spirit, in form or in size, sometimes a bit of everything. Completed art is dead art. What I present to the world is not completed pieces, but a capture of myself and my thoughts within a timeframe that inspired the piece, and I hope to inspire others to do the same with their life. I always tell myself and people who are close to me: “Be the pond, not the water.”

The act of viewing and interpreting art is also a part of proving its liveliness. To be able to converse with people not only about my art and experience, but also their experience, and my newer experience after the creation of said art. I think that’s what makes my work what it is: a flow of consciousness.

Nguyen Minh Tri (Tonee) | Mostly Air

Nguyen Minh Tri (Tonee) | Mostly Air

How does repetition help you cope with ADHD, and how has this practice shaped your relationship with time and patience?

A major thing with ADHD is the inability to sit still and focus on things that produce little dopamine. In the beginning of my journey, I had to turn on a Youtube video or a game to be able to sit and create. As I tried and trained my stillness and ‘zen,’ I started to enjoy the little things that come with creation and art. Feeling the materials that are at hand: the humming of the air conditioner, the roughness of aluminium wires, the hot and cold of hot glue, the rubbing of ink against the canvas, past memories, daily conversations.

I like having conversations with my art. Sometimes, it is pleasant, at times, it is frustrating. But like a close friend, I value it, and I hope that it values me.

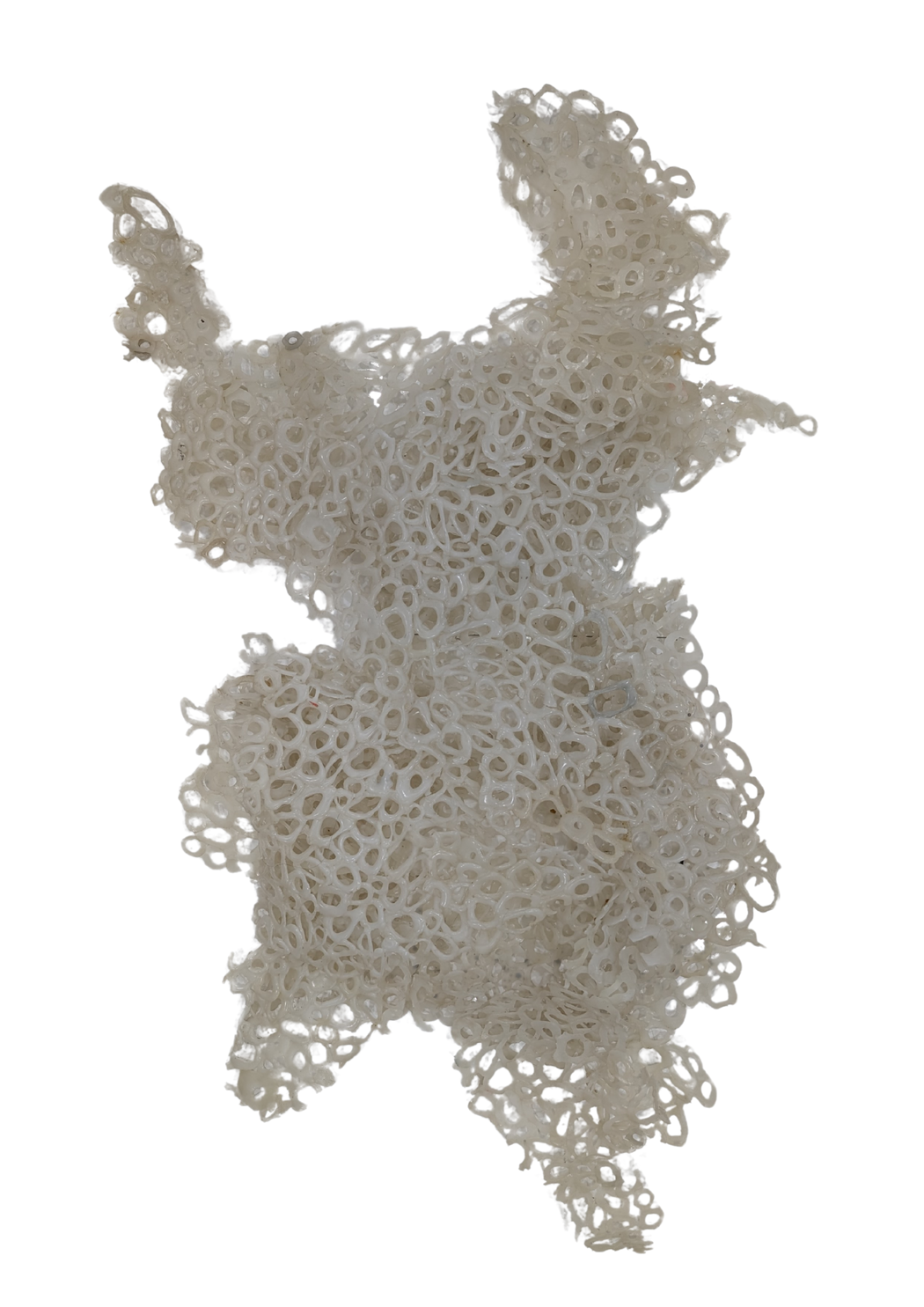

Nguyen Minh Tri (Tonee) | Octopus Heart Hair Hat

Nguyen Minh Tri (Tonee) | Octopus Heart Hair Hat

The piece “Octopus Heart Hair Hat” has a powerful symbolic weight. What emotions or memories does it hold for you?

The hat is inspired by the knit hat that Vietnamese parents usually give to their kids that mimics the appearance of having a different hair style. I imagine if someone never grows up and keeps wearing the hat, the wool hair would become your hair, and hair must grow.

In Vietnam, there’s a saying that goes: Cái răng cái tóc là gốc con người (Teeth and hair are the roots of humans). The act of knitting is traditionally women’s labour. Long hair gets tangled and messed up, but you are too attached to cut it off, so you hold onto it like a big weight.

I don’t have a specific memory of the work, but a general feeling toward childhood. How much of it am I dragging toward the present and future.

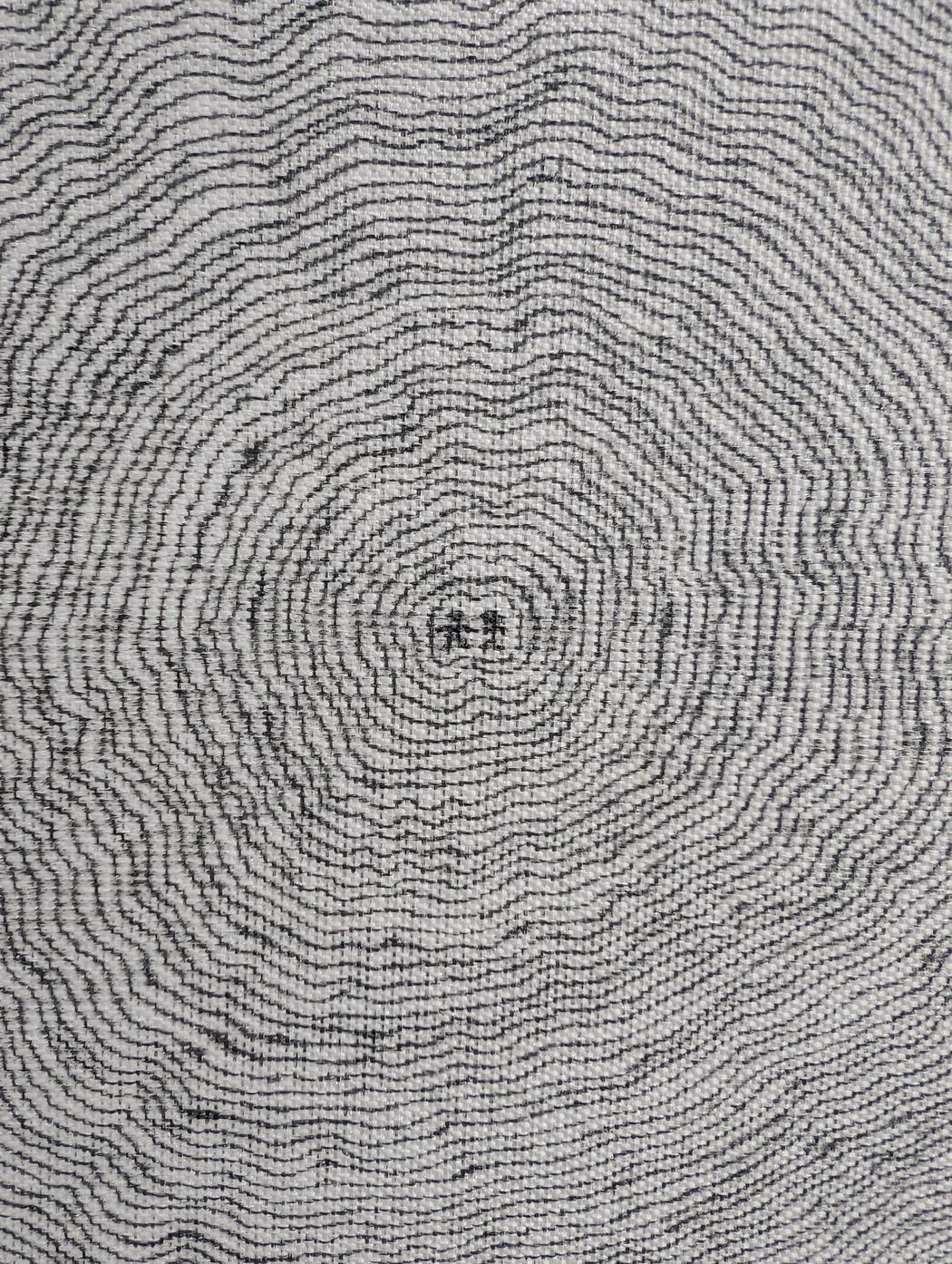

Nguyen Minh Tri (Tonee) | This Is Me Trying

Nguyen Minh Tri (Tonee) | This Is Me Trying

In “Fragile” you use aluminium wire, traditionally meant to support bonsai trees. How do you reinterpret this material as something fragile yet expressive?

The work is in my series that tries to use the glue that sticks and creates structures, to become the structure by itself. By the word ‘fragile,’ I am toying with the rigidity of the work, physically and fundamentally. It is very ironic, metal and fragility. I really wish to have physical exhibitions where viewers can participate in shaping the works themselves, by physically touching and bending them. I believe there’s so much emotion and decisiveness in bending metal, the fear of mishaping them, because metal remembers. Each bend will forever have its mark within the metal.

Aluminium wire is a fascinating material, I really wish to popularize its use in art and in general. Very dependable yet flexible, many fun vibrant colors also!

Many of your works deal with tension between control and chaos. How do you navigate this balance in your art and in life?

It’s a fine line, but I don’t really aim to balance it in my art. I think that art is not always meant to reflect life correctly. I use art as a way to balance my life. Most of the time, life interferes with my art, but sometimes art interferes with life. I would love to make my art more chaotic if I ever learn to code and create machinery to make art that can move on itself. But when viewers move my art by themselves, it’s already chaotic already! I love to have more controlled chaos, and more tension if possible.

Nguyen Minh Tri (Tonee) | Fragile Hands, Fragile Minds

Nguyen Minh Tri (Tonee) | Fragile Hands, Fragile Minds

What role does empathy or self-reflection play in your art practice?

For me, empathy isn’t just for people; it is a form of ‘material listening.’ When I work with aluminum wire, I have to empathize with its limits. If I force it to bend against its grain, it snaps or weakens; if I listen to where it wants to go, it flows.

There is a concept called panpsychism; the idea that mind or consciousness is a fundamental feature of all things. While I don’t know if wire has a soul, I treat it as if it does. Creating art is my way of externalizing that internal dialogue. If I can be gentle with a stubborn piece of metal, perhaps I can be gentler with my own stubborn thoughts. Art becomes the bridge where my internal world meets the physical world, and empathy is the gravity holding them together.

Nguyen Minh Tri (Tonee) | This Is Me Trying Ink

Nguyen Minh Tri (Tonee) | This Is Me Trying Ink

Do you consider your artworks as self-portraits in some way — extensions of your thoughts or emotions?

Absolutely, but I view them less as a mirror and more like a shed skin or an exoskeleton. Snakes shed their skin to grow; they leave behind a perfect replica of who they were, but they are no longer that creature. My artworks are past selves frozen in aluminum and glue. They allow me to step out of a specific emotion or obsession by giving it a physical body, separate from my own.

Returning to the idea of the pond: if I am the pond, these artworks are the ripples captured at a specific moment of impact. Interestingly, because I want viewers to physically interact with and bend my works (like in Fragile), the ‘self-portrait’ is never static. As soon as a viewer touches and alters the piece, it stops being just my portrait and becomes a collaborative record of our interaction. It’s a portrait of me, edited by you.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.