Rui Wang

Your project “Not Everything Was Seen” explores absence as presence. Can you tell us more about how this concept emerged and why it feels important to you?

I didn’t come to “absence as presence” through theory. It surfaced while I was between places, walking with a film camera at quiet hours and noticing what remains after a moment passes: the way dusk sits on a window, a curtain settling after someone leaves, the tide smoothing over footprints. Those traces felt charged but not declarative, more like echoes that keep speaking after the scene is over. The title, Not Everything Was Seen, acknowledges that feeling and accepts incompleteness as part of how we truly remember.

The idea matters to me in two ways. Emotionally, it’s honest: memory is partial, and the gaps carry their own weight. Ethically, suggestion feels more respectful than exposure; it lets me acknowledge a scene without claiming it and invites viewers to co-author the reading. My background in Chinese art shaped this approach: liubai, or deliberate blankness, became active negative space, and restraint became a way to let images breathe.

I work on analog film with available light and a limited palette, slowing down to listen for timing rather than chase events. The series moves through scenes where presence is felt more than shown: the shadow of someone alone at dusk, the instant a flock of birds passes overhead, a person pausing to watch the sunset at twilight, a shoreline breathing at blue hour. Sequenced like a quiet conversation, the photographs don’t explain a story so much as hold one, letting tenderness appear in what almost, but not entirely, comes into view.

Rui Wang | What Hides In Light | 2025

Rui Wang | What Hides In Light | 2025

Many of your works deal with traces, fragments, and what is left unseen. How do you translate these abstract ideas into visual form?

I translate traces and the unseen by working toward decisive moments. I begin by naming the feeling I want the image to hold, then set constraints that make that feeling visible: a limited palette, available light, and a point of view that withholds as much as it reveals. In the field I pre-visualize the frame and wait for the alignment of light, gesture, and distance. When that instant arrives, the fragment becomes legible without being overexplained.

Analog film slows me down, so timing and patience do the real composing. In editing, I make small work prints, live with them on the wall, and sequence in passes: first for instinct, then for structure, then for nuance. Negative space stays active, recurring motifs act as quiet anchors, and scale shifts help create a measured cadence.

This carries into my design practice as well. Design and photography are two languages for the same narrative impulse. In design I translate the feeling into system rules: a restrained palette tied to meaning, typography that sets cadence, grids that define pacing, motion that breathes, and image direction that leaves room for interpretation. Photography gives me mood, timing, and sensitivity, design returns structure, clarity, and coherence. Together they keep the story intact while allowing the viewer to enter and complete it with their own memory.

What role does photography play in your practice compared to your design work? Do you see them as separate fields or as one continuous language?

I see photography and design as one continuous language spoken in two voices. Both begin with feeling. Photography is how I listen and discover; design is how I shape and communicate. The previous question touched on decisive moments and omission. Those same ideas connect the two: I look for what is sensed rather than shown, then give it a form the audience can read.

Photography trains attention and restraint. Working on film slows me down, sharpens timing, and refines my sense of light, palette, and atmosphere; sequencing teaches editorial flow, where a pause belongs, and how two images speak without captions. Design returns structure and clarity to those intuitions. I think in grids, scale, rhythm, and tone so a series holds together, and in brand work this becomes a system that protects voice across channels. Ethically, both practices leave room for the viewer: photography notices without claiming, design clarifies without closing. Put simply, photography helps me find the story, and design builds the vessel that carries it.

You have worked with major global brands like Disney and Nike. How does your personal artistic practice differ from your commercial design projects?

My personal practice is slow, observational, and led by mood, while commercial work is brief-driven, strategic, and built to scale. With film I accept ambiguity and edit in sequences until the feeling is right; with brands I translate insight into systems like type hierarchy, color logic, grids, motion, and image direction. Even so, the backbone is the same: storytelling. Whether I am designing or photographing, I start with the emotion I want the viewer to carry and then build the form that can hold it.

In your creative philosophy, you describe every visual as a vessel for storytelling. Could you share a moment when this idea became especially clear in your work?

To make this idea tangible, I will share two examples: one photograph from my series Not Everything Was Seen and one design project.

Rui Wang | Not Everything Was Seen

Rui Wang | Not Everything Was Seen

Photography (image 1, Not Everything Was Seen): This picture was made at the beach near dusk. Two people sit facing the water, almost absorbed by the horizon. Nothing overt happens, yet distance, posture, and the soft spread of light carry the feeling. I framed wide, kept the horizon low, and left generous negative space so companionship, time, and a trace of longing could surface without explanation. This is the core of the series: absence feels present, ordinary scenes hold tenderness, and viewers complete the story with their own memories.

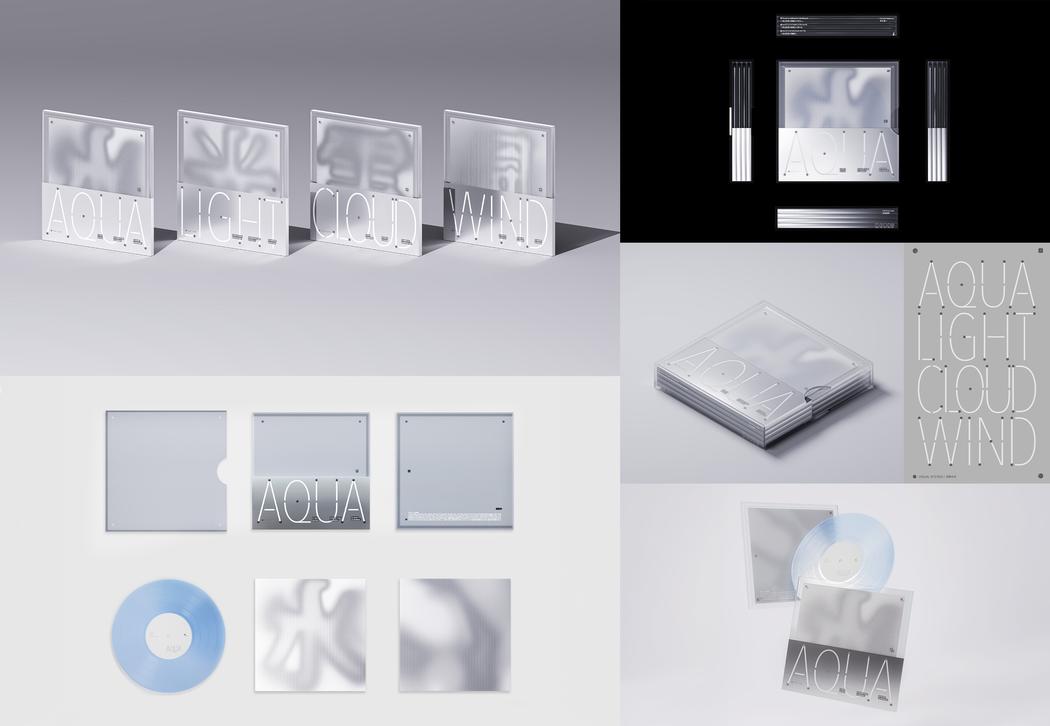

Rui Wang | Soundscapes Archive

Rui Wang | Soundscapes Archive

Design (image 2, The Soundscapes Archive): The brief was to translate elements of the environment into a record identity. I used translucent layers, restrained type, and a modular grid so “aqua, light, cloud, wind” could be read and felt. As light passes through the package, shadows and textures shift, and the system begins to behave like the music. Typography sets cadence, materials hold atmosphere, and the object becomes a vessel for listening.

In “Not Everything Was Seen”, love appears as something fleeting, sometimes hidden. Do you think art can capture emotions that resist visibility?

Yes, but not by pinning emotion down. Art cannot show love directly; it can create the conditions in which love is felt. In Not Everything Was Seen I work with timing, distance, and omission: a pause between two frames, a figure turned away, dusk light held on water. Sequencing becomes the grammar, negative space the tone, and small recurring motifs act as echoes. Viewers recognize the trace and supply the feeling.

I approach design the same way. You cannot show empathy or tenderness in a logo, but you can let type cadence, spacing, materials, and image direction carry them. In both practices, suggestion is more faithful than explanation. We may not see love itself, yet we can sense it in what remains after the moment passes.

Rui Wang | Where I Begin To Disappear | 2025

Rui Wang | Where I Begin To Disappear | 2025

Your work has been recognized by institutions such as Red Dot, IPA, and MUSE Awards. How do these acknowledgments influence your creative journey?

I am grateful for those recognitions because they validate a cross-disciplinary path and give partners confidence in a narrative-driven approach. They open doors to larger briefs, deeper collaborations, and practical benefits like visibility, publishing, and exhibition opportunities. Just as importantly, they strengthen my confidence in the artistic road I have chosen, encouraging me to create more, take smarter risks, and keep refining the work with patience and care.

I still treat awards as checkpoints, not destinations. They raise the bar and remind me to keep the craft honest, support younger creatives, and measure success by what matters most: whether the work carries feeling, reads clearly, and stays with the audience after the moment has passed.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.