Michaela Chittenden

Where do you live: Albany, New York

Your education: Current college freshman at University at Buffalo, major in History, minor in Art + Music

Describe your art in three words: Narrative · Nostalgic · Human

Michaela Chittenden | Where Our Soul Was Born | 2025

Michaela Chittenden | Where Our Soul Was Born | 2025

Your work revisits pivotal moments in American history. How do you choose which historical events to portray, and what draws you to them emotionally?

I’ve been known to be imaginative and constantly daydreaming, even in class. Many of my ideas came from the seat of my history classes. Learning history through dates and events was never enough for me, I always wanted to understand it through the eyes of the people who lived it. I wasn’t interested in memorizing when a battle took place, I wanted to know how an old farmer felt before charging into the field or how a mother reacted when her son joined the rebel side. I’m drawn to eras where we’re taught more about the politics and economics than the human cost. Creating these pieces helped me see history as more than a list of events, as lives and emotions.

You mention that your art explores how America remembers itself. What, in your view, is the biggest difference between memory and history?

Like any country, America understands its history through art. Music, literature, visual art, and now film and television shape how we remember our past, for better or worse. These creative reinterpretations are powerful because they reveal how we view ourselves and our ideals. Of course they often differ from reality and can even be harmful if we forget that difference. History is a record of facts, actions and reactions, but memory is where our humanity lies. What we choose to remember and what we choose to forget says as much about us as history itself.

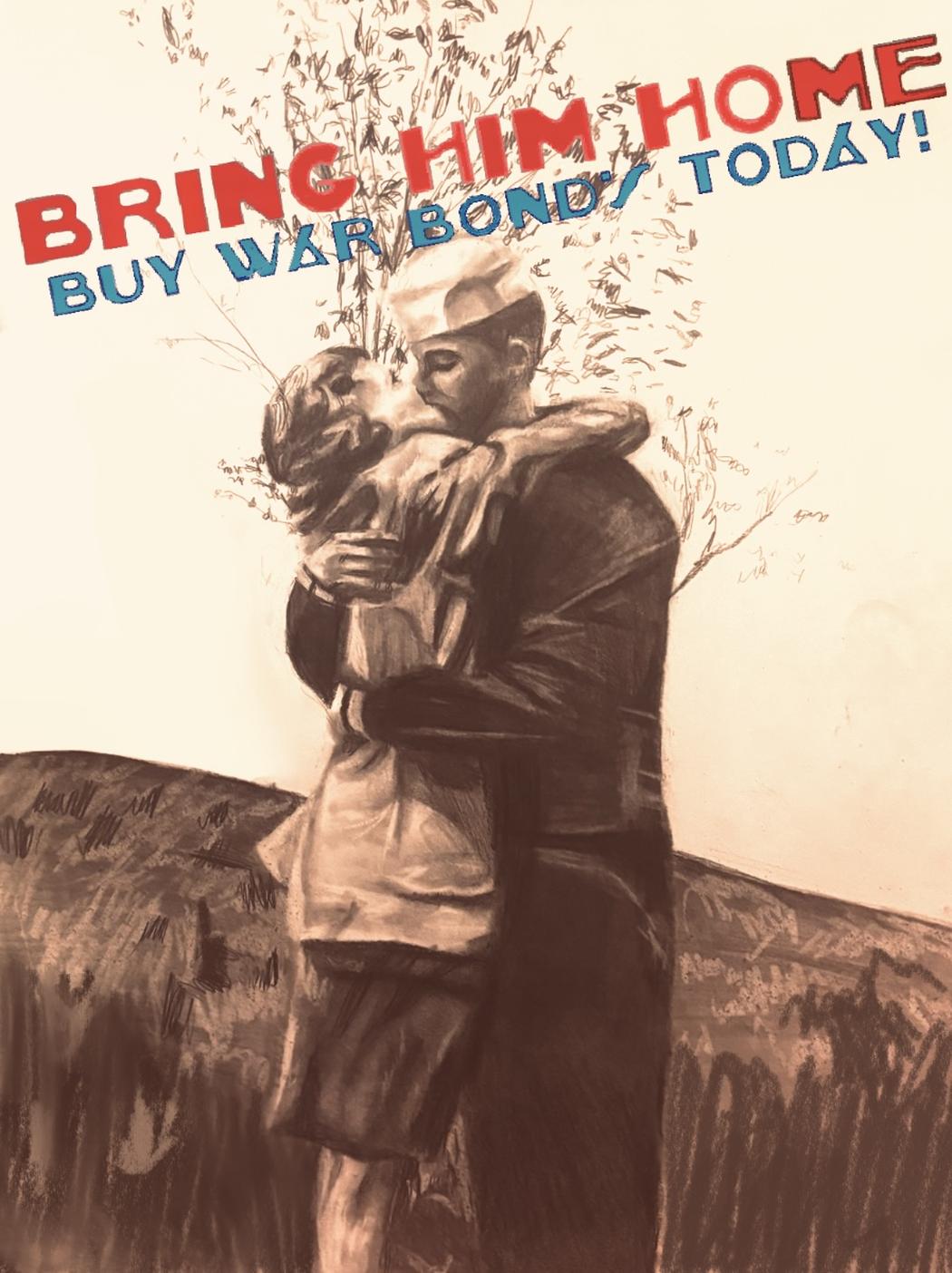

Michaela Chittenden | Bring Him Home | 2025

Michaela Chittenden | Bring Him Home | 2025

Charcoal plays a central role in your practice. What do you find most powerful about working in this medium, especially when dealing with themes like war, tragedy, and hope?

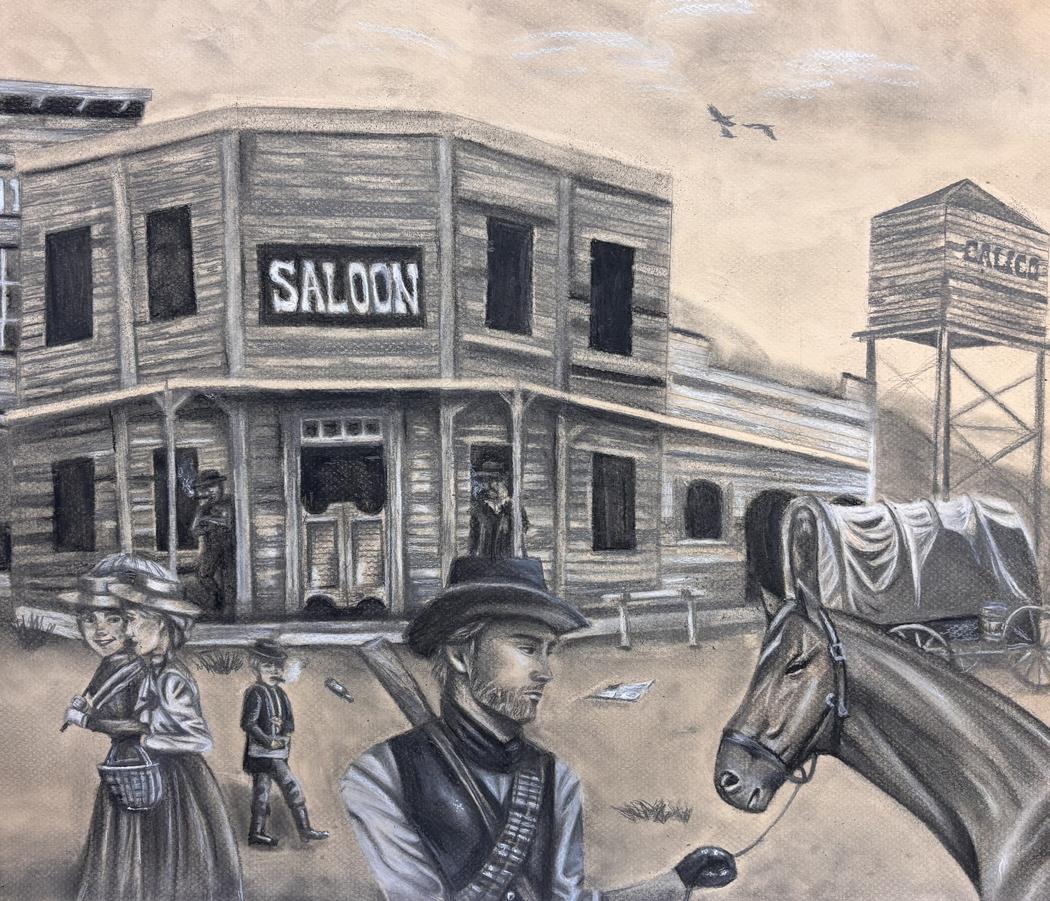

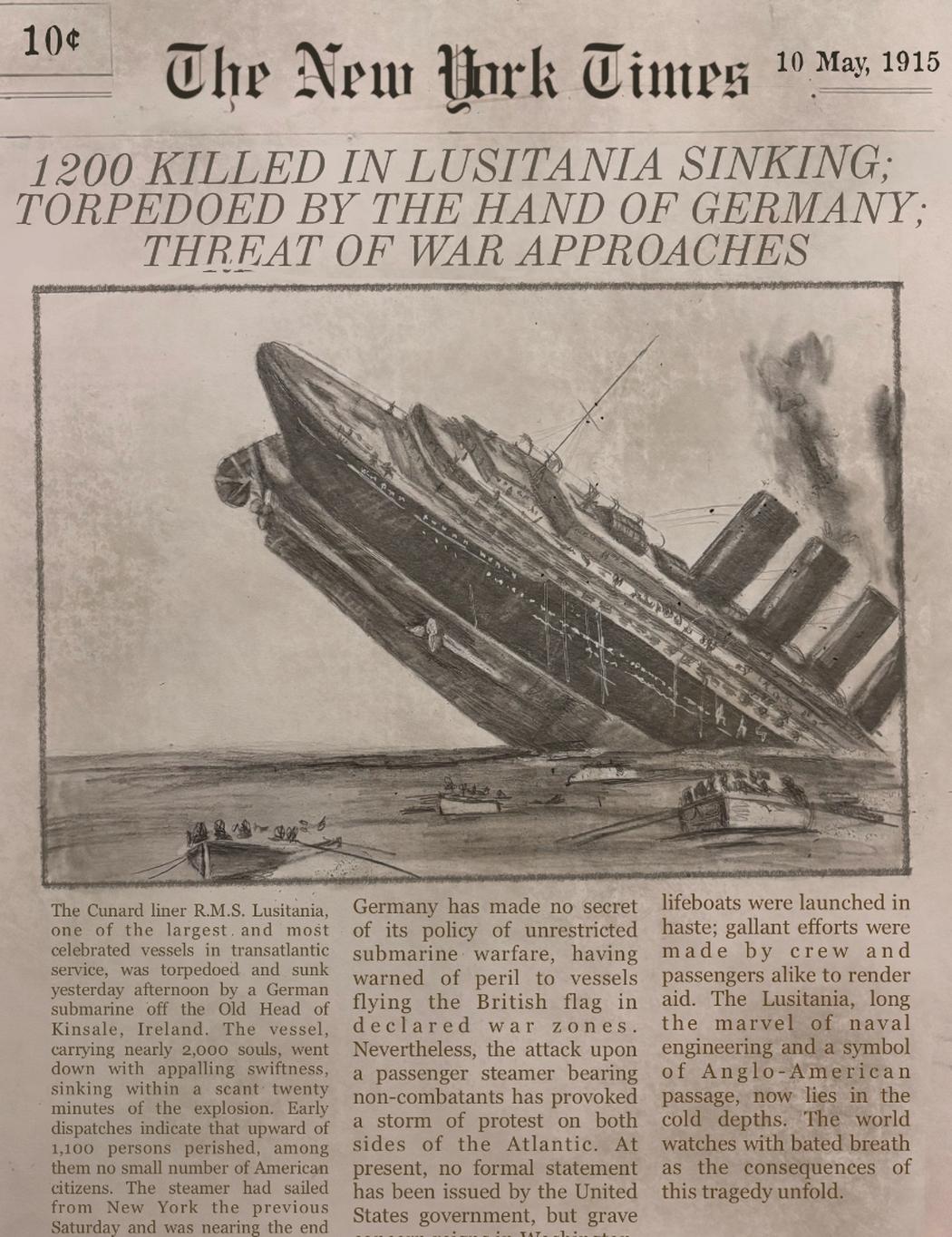

Charcoal carries expressive weight with its dramatic contrasts and raw emotion. It’s one of the oldest art materials, which gives it a timeless and almost ancestral quality. I love its versatility and the way its meaning changes depending on the technique. A pressed vine stick feels harsh and stubborn, while a softly blended surface conveys tenderness and reflection. That flexibility made it the perfect medium for my themes. In the Western piece, rough smudges create a rugged tone, in Lusitania, tight lines evoke dread, in the WWII drawing, soft blending suggests hope and resilience. It amazes me that one material, with different techniques, can express all kinds of human emotions.

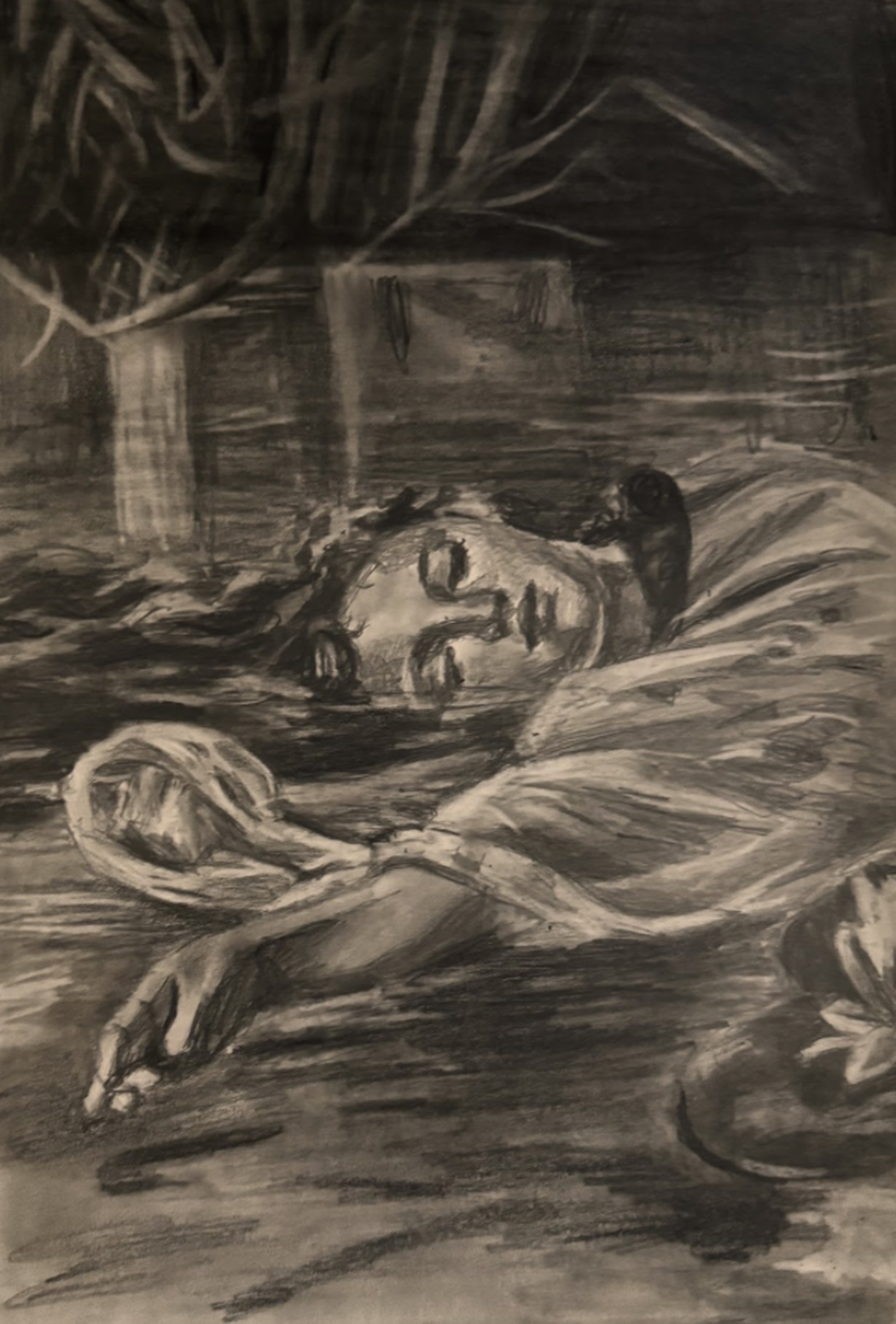

Michaela Chittenden | Ophelia Friedrich Portrait Study | 2025

Michaela Chittenden | Ophelia Friedrich Portrait Study | 2025

Several of your drawings reimagine wartime imagery and propaganda. What inspired you to reinterpret these familiar symbols in a more intimate, human way?

When we learn about wars in school, they’re often taught in a distant and impersonal manner. Numbers replace people, “400,000 dead” is told as a statistic instead of a tragedy. We forget the individual stories like the mothers who lost their boys, the wives who lost their loves and the children who grew up without fathers. Instead, we hear about economic recovery or military strategy. My goal was to rehumanize these histories and to turn familiar symbols and propaganda into something intimate and emotional. I wanted to tell the story not through generals or politicians, through the ordinary people who lived, suffered and endured. With this, I aimed to communicate the difference between national image and personal experience.

Michaela Chittenden | The American Dream | 2024

Michaela Chittenden | The American Dream | 2024

Your statement mentions the idea of “connection — between eras, people, and memory.” Can you describe a moment in your work when this connection felt especially vivid or personal?

The moment that connection felt the most vivid was when I noticed a common thread of romanticization running through several pieces. The Wild West, the Roaring Twenties, the “noble” Fifties, all of these eras are remembered with longing, even by those who never lived them. They’ve been aestheticized time and time again in the media, and their hardships were overlooked by nostalgia. I wanted to confront that tension between beauty and truth, between the stories we tell about the past and the realities we overlook, poverty, lawlessness, racism and sexism. That realization made the work feel alive to me, because it showed how memory itself can distort history.

Michaela Chittenden | When The West Was Wild | 2025

Michaela Chittenden | When The West Was Wild | 2025

How do you approach research for each piece? Do you start with historical documents, photographs, or emotional intuition?

My research process changes with each idea. I start with an event I already know, then look beyond the textbook version. I read first-hand accounts like letters, diaries and personal belongings because I don’t just want to know what happened, I want to know why it mattered. What were the social pressures, the fears and the hopes? Understanding those emotional and cultural contexts helps me translate history into something human and relatable.

Michaela Chittenden | When Peace Sank | 2025

Michaela Chittenden | When Peace Sank | 2025

As a student artist, how do you see your artistic voice evolving in the future? Are there other periods or cultural themes you hope to explore next?

Over the past few years, I’ve grown a lot as an artist from relying on references and creating simple portraits to creating full compositions without that dependence. I’m proud of that progress, but I still have so much to learn. Right now, I’m focusing on improving gesture and expression, since my figures can sometimes feel a bit stiff. I plan to continue exploring historical narrative drawing but expand beyond American themes. I plan to study East Asian, Medieval European and Middle Eastern art to understand how different cultures use art to tell their stories. Stepping outside my comfort zone is essential, growth only happens when we’re willing to be uncomfortable.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.