Jeronimo de Moraes

Where do you live: I split my time between Shirley and Brooklyn (and boroughs), NY

Your education: Bachelors in Communication from Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro with a major in Broadcasting

Describe your art in three words: Personal · Layered · Raw

Your discipline: Visual arts — moving and still images

Website | Instagram

What first drew you to the Piscinão de Ramos as a subject? Was there a particular moment or scene that inspired this series?

Piscinão has always been a kind of dream subject for me. The social and cultural energy there is incredibly rich — visually striking and full of life. Rio is a city of constant contrasts, and places like the Piscinão embody that tension in the most beautiful way. They’re spaces where opposing forces — inequality and joy, precarity and pride — somehow coexist and create these cultural sanctuaries that feel deeply human.

A lot of what becomes popular culture in Brazil actually originates from places like this, which are collective monuments of resistance, identity, and belonging for working-class communities. I’m fascinated by that — it gives me butterflies, honestly — that mix of vitality, vulnerability, and connection.

And the timing felt right. After living away from Brazil for nearly twenty years, returning made me see Rio with new eyes. It made me want to reevaluate my relationship with the city — not through nostalgia, but through renewed attention and affection for what still endures there.

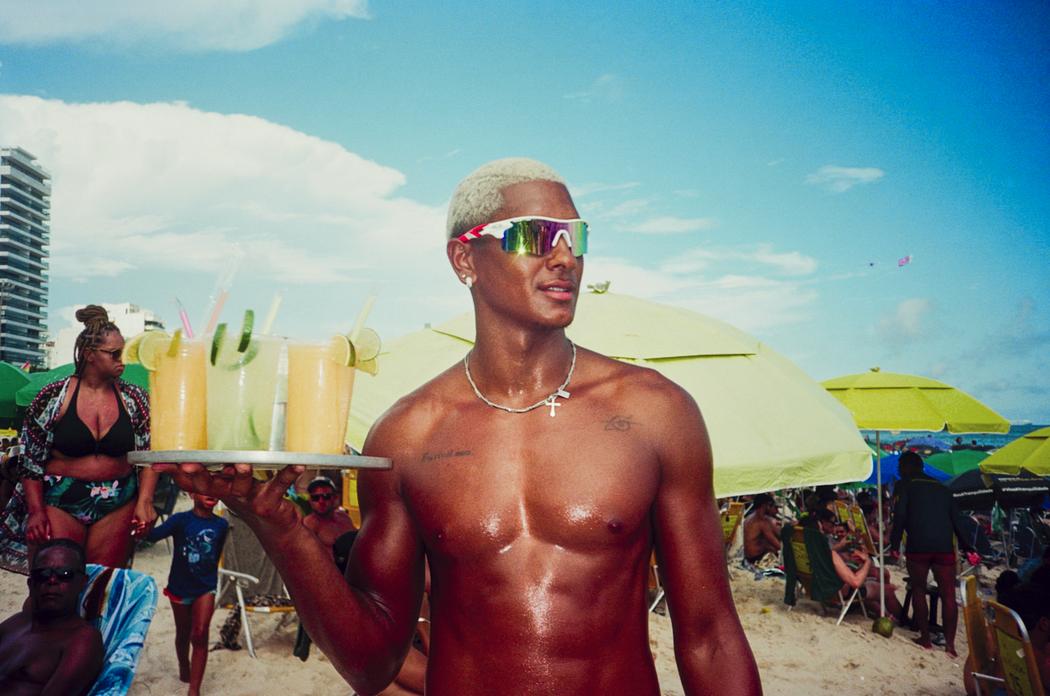

Jeronimo de Moraes | Riviera Roquete Pinto | 2025.jpg

Jeronimo de Moraes | Riviera Roquete Pinto | 2025.jpg

How did your own memories of Rio de Janeiro influence the way you approached photographing this “Riviera”?

Coming from Rio and knowing its culture so well really shaped the way I approached the “Riviera.” That familiarity gave me access to people in a very personal and genuine way. It wasn’t about arriving as an outsider — it was about reconnecting with something I already understood deeply, and letting that shared background create trust and openness in front of the camera.

The project challenges the postcard image of Rio — how do you see the relationship between representation and inequality in your work?

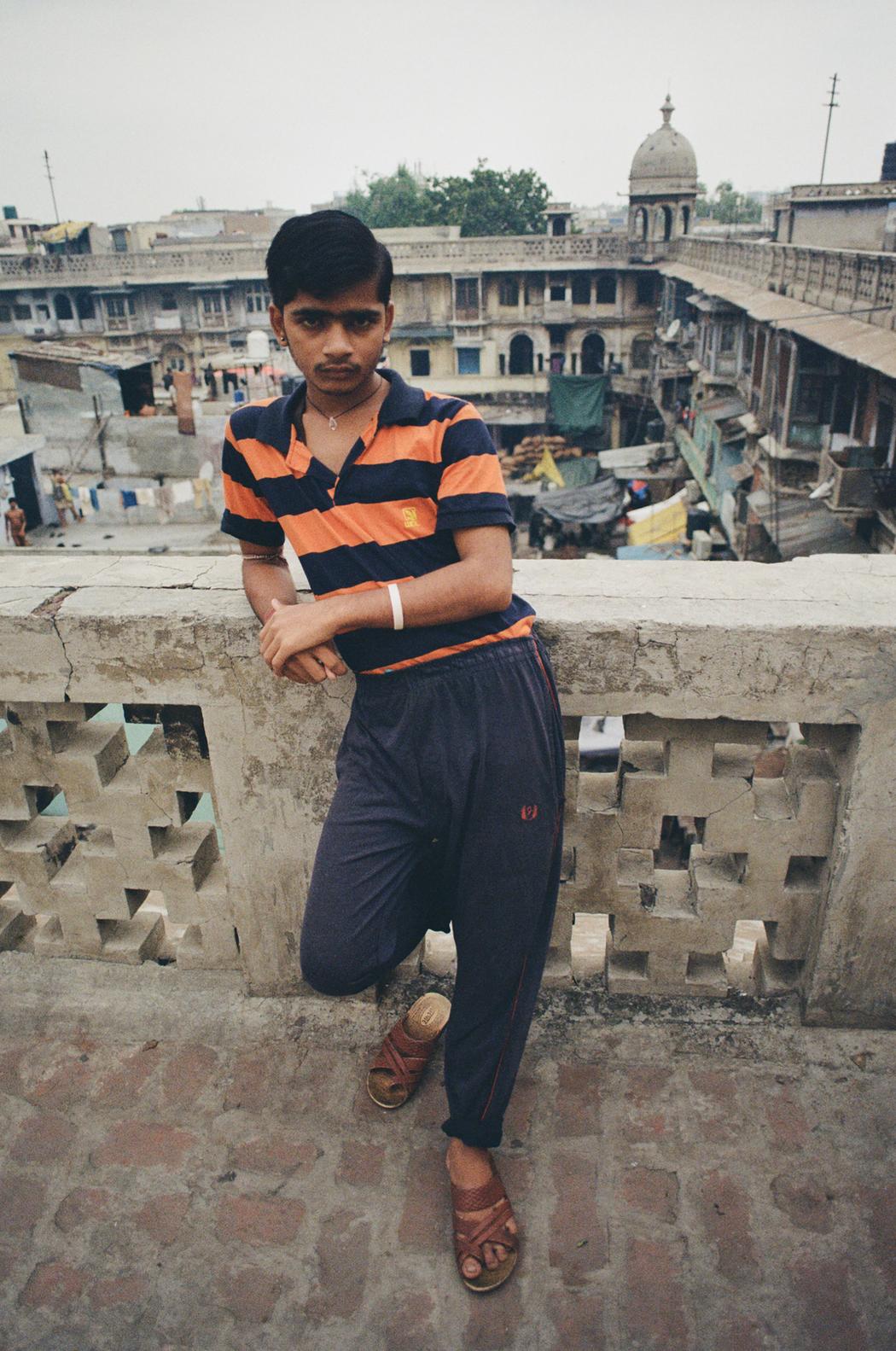

This question really sits at the heart of my ongoing dialogue with Rio — especially as I return to make new work there. I’ve always been drawn to what I’d call secondary narratives — stories that exist just outside the mainstream but deeply shape it. The term counterculture feels outdated; these communities aren’t oppositional, they’re simply mainstream-adjacent — vital, creative spaces that exist in parallel and often set the tone for the culture that eventually becomes widely consumed.

My father’s family came from very modest circumstances, and being around relatives who lived that reality gave me a grounding perspective — a kind of humility that stayed with me. So, in many ways, I feel a responsibility to use my work as a positive voice for those who live and create from the margins.

This theme is also very much aligned with the last twenty years of my life — as a Latin American from Brazil trying to find my place in New York. That experience of navigating between visibility and invisibility, privilege and otherness, constantly informs how I look at the world and the people I photograph.

Ultimately, the project — and my work in general — is about expanding representation beyond the postcard image, toward a more honest and inclusive reflection of the city and its people.

Your images have a powerful balance between people, color, and urban structure. How did you decide on the visual tone and rhythm of the series?

It’s interesting because the visual tone of this project marks a real departure from much of my earlier work, where I’ve mostly relied on natural light. In Riviera Roquete Pinto, the use of flash became central — both aesthetically and processually.

Aesthetically, the flash creates a heightened, almost theatrical atmosphere. It turns the subjects into protagonists, pulling them forward from the background and giving each scene a sense of immediacy and depth. It helps translate a three-dimensional reality into a two-dimensional image that still feels alive, emphasizing people and the small details that define their presence.

But the flash also works as a social tool. Flash photography has deep roots in celebrity and nightlife culture — when that light hits, people instinctively feel seen, important, celebrated. Using it in this context transforms a simple portrait session into a moment of acknowledgment and empowerment.

Can you tell us about your process on site — how do you interact with the community when photographing such personal environments?

I always like to work with a local producer, and this project was no different — in fact, I ended up hiring two people who were absolutely essential: Lucas Petitdemange and Jean Barreto.

I first connected with Lucas, whose task was to find someone truly local who could help navigate the social nuances of entering an area like the Piscinão, which is heavily shaped by community dynamics and informal power structures. That’s how I met Jean — and honestly, this project wouldn’t exist without him. He grew up there, his parents still live nearby, and he wrote a master’s thesis on the very subject: “Entre o mar e o concreto: a invenção da Praia de Ramos — Lazer e balneabilidade nos subúrbios cariocas (1940–2002).” Reading his research before shooting really helped me connect the historical and emotional layers of the place.

On the day of the shoot, it was the three of us — Lucas handling logistics, and Jean and I walking around talking to people. Jean was also photographing, which made the whole thing feel less like a production and more like a collaboration. People were curious about what we were doing, and once we explained the project, they felt genuinely excited to represent the “Riviera” well.

We took maybe four laps around the whole place, taking our time and meeting new people every round. Each lap was about two hours, and it was beautiful to see how some people started warming up to us by the third time they saw us. The beverage vendors kept offering us free drinks because we were out there working under the hot sun — it really showed the incredible sense of community that exists there.

It’s amazing how, once people start sharing their stories, they open up to being photographed — the process becomes mutual. And yes, maybe a few caipirinhas helped with that too. But in the end, it’s about arriving with an open heart, a sense of respect, and genuine curiosity about people’s lives.

You often work between documentary and fashion aesthetics — how did these two worlds meet in this project?

When I photograph people, I think the fashion aesthetic naturally finds its way in — it’s almost ingrained in how I see and compose an image. I started out as a photojournalist, so storytelling has always been central to my practice. But fashion taught me to pay attention to form, gesture, and presence — how visual language can shape perception.

Even though Riviera Roquete Pinto has a more documentary foundation, bringing a fashion sensibility to it helped elevate the subjects and highlight their individuality. The tension between these two worlds — fashion’s stylized precision and documentary’s raw honesty — creates a space where people can appear both real and radiant, grounded and iconic at the same time.

The project speaks about resistance and joy — what emotional reactions do you hope to evoke in the viewer?

I think photography has this incredible quality of inviting endless scrutiny — you can look at an image over and over and always discover something new. That’s why it’s so important to listen to people before you photograph them.

When you have connection through a human story, your photograph instantly becomes a document of an interaction and I want people to just stand there and stare at every single detail and hopefully the longer they stare the more they feel their own humanity.

Ultimately, I hope that viewers sense the dignity, joy, and complexity of every single person portrayed and keep coming back to this reflection.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.