Simone Sanna

Where do you live: Alghero

Your education: Master’s degree in architecture (cv Design)

Describe your art in three words: Errors, Aesthetic, Research

Your discipline: Architectural Drawing

How did your studies at the University of Sassari (UNISS) and your PhD research in Alghero shape your approach to architecture and design?

I see my university years as the time when I discovered and nurtured my passion for architecture. I was immediately drawn to composition and representation, and ongoing dialogue with peers pushed me to improve and to keep exploring new directions – what I like to call a “serious game,” borrowing a colleague’s expression. My PhD focuses on Generative AI applied to architectural drawing; it lets me pursue lines of inquiry I had only glimpsed during my studies. So far, these super-digital tools haven’t radically changed my approach: substantial visualization work – graphic or more design-oriented – still starts by hand, to steer results toward the original idea.

What drew you to focus your doctoral research on the intersection of Generative AI and Architectural Design?

As mentioned, my research centers on the intersection between Generative AI and architectural drawing. Throughout my studies I was committed to representing architecture in a way that conveys space – and the feelings it can evoke. The possibility of generating those elements with super-digital tools struck me as worth investigating, especially given how widely these tools are spreading across many fields. In contexts like this – outside a strictly academic setting – design isn’t excluded; I frame it as a search for spatial and material coherence across the synthetic images produced. In practice, it’s hard to represent without designing, and hard to design without drawing.

How do you integrate generative artificial intelligence into your design workflow?

This is exactly what my dissertation explores. Here, “design” mainly means graphic design. It isn’t simple to assign these tools a precise place; figuring out how to integrate them critically is the core of my work. I find them very interesting and useful when used consciously, but it helps to look beyond surface aesthetics and ask whether what they produce is truly useful for work or research. Right now, these tools come in at the final stage of the graphic–design process: I first sketch and build a visual concept by hand; imagining composition and atmosphere helps me craft a better prompt and reduce unwanted hallucinations. That said, letting yourself get “lost” in certain synthetic “hallucinations” can also open up unexpected viewpoints.

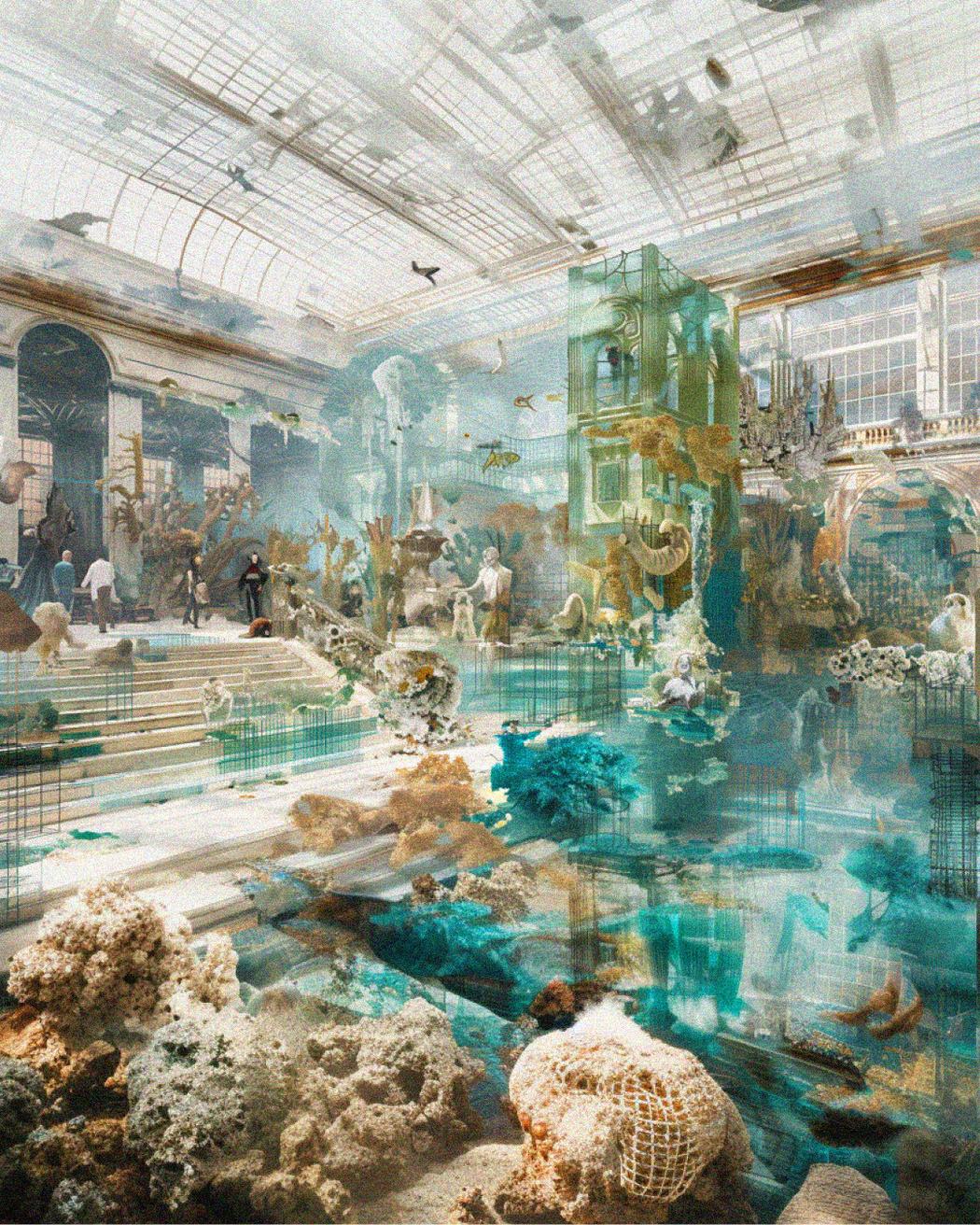

Simone Sanna | Abandoned Hallucination | 2025

Simone Sanna | Abandoned Hallucination | 2025

Can you share an example of how AI tools have inspired or transformed one of your recent projects?

The image I presented originally had a different setup. The graphic project is based on a contest organized by the student association at the Department of Architecture, Design, and Urban Planning in Alghero, built around the theme Nomade, understood both as “unfinished” and as “nomadic.” The mood and key elements – like the pink drapery and water – were already there, but the architectural scale differed: the initial idea envisioned a series of abandoned urban pavilions. AI-generated suggestions made me rethink the scale, allowing me to translate the original idea into an image that was more evocative and more consistent with the intended references.

In your opinion, what are the biggest opportunities and challenges when architects use AI?

Opportunities are numerous: an almost limitless library of sources, continuous feedback from these super-tools, ongoing research to “train” one’s eye, and the need to define the project clearly up front. All this fosters constant reflection, improves skills and knowledge in an active, evolving process alongside the machine, and reduces arbitrariness. The biggest challenge is preserving authorship: moving past immediate aesthetics and pursuing coherence between intention and outcome – between the mental image of the project and the synthetic image produced.

Your artworks blend architectural space with dreamlike natural and aquatic elements. What inspires these imaginary environments?

The project stems from the Nomade competition, but I’ve long been fascinated by futuristic and dystopian visions of cities where nature reclaims the built environment. That sense of what could happen – a nearly surreal take on reality – has been with me since my final university years, and cinema has also helped shape this imaginary. The aim here was to reveal the possible beauty within that vision: architectures of the past turned into shelter for a nomadic population, holding traces of what once was and hosting emergent forms of re-naturalization.

How do you see AI-driven architecture contributing to sustainability and environmental responsibility?

AI doesn’t help much without a clear design direction. What I find compelling – always with a critical eye, and specifically regarding Generative AI for graphic output – is the chance to reinterpret certain “hallucinations.” Trained on vast image datasets, and through the semantic link between prompt and image, these models sometimes surface ideas we hadn’t considered – like the change in architectural scale in the image discussed earlier. Giving yourself room to shift perspective and visualize alternative scenarios helps bring current issues and possible interventions into focus, turning suggestions into practical developments. That step back to recalibrate one’s gaze is, in my view, one of the most valuable contributions these tools can offer.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.