Michela Nanut

Year of birth: 1981

Where do you live: North Italy (near Garda Lake)

Your education: degree in philosophy of science

Describe your art in three words: dreamlike – ironic – silent

Your discipline: digital illustration

Website | Instagram

Your background in Philosophy of Science seems quite unique for an illustrator. How does your academic training influence your work as an artist?

Philosophy was my first and greatest love, and studying it has given me a valuable tool to approach illustration in an active way. I’m not so much interested in providing answers as am in asking questions, inviting the viewer to reflect. It helps me question our beliefs and the symbolic system that accompanies them on a cultural level, allowing me to play with meanings, deconstruct them, and recombine them. In this sense, every image becomes an open dialogue rather than a definitive statement.

Your project “Illustrated Stories of Minor Migrants” addresses important social issues. What drove you to work on this project, and what message did you hope to convey through the illustrations?

I was involved in this project by journalist Claudia Bellante and photographer Mirko Cecchi from Raccontami.org. Together, we wanted to tell the stories of the young people portrayed, showing the viewer that they are full of extraordinary and harmonious dreams, not driven by terrible criminal intentions.

People who cross continents do so because of objectively devastating causes-war, famine, ethnic persecution-but the wind that carries them is the same that guided Ulysses in his wondrous journey across the Mediterranean. Ulysses himself, in The Divine Comedy, reminds his companions that they were created to follow virtue and knowledge.’ The virtuous desire for discovery accompanies every journey, including migration.

Michela Nanut | Il passeggero | 2023

Michela Nanut | Il passeggero | 2023Can you tell us about your creative process? How do you approach a new project, from concept to final artwork?

I usually draw inspiration from a line of poetry, a phrase I overhear somewhere, or a scene from a film. It’s as if I have a vision of an image, and from there, I start by sketching on paper. Other times, I’m asked to illustrate a specific concept; in that case, I first create a mind map, write down a brainstorming session until the right idea comes to me.

Once I have my pencil sketches, I set up photo sessions to stage what I want to draw, photographing myself or other people. From the photograph, I trace some parts on my iPad, while others I redraw freely. This is how I create the digital sketch.

At this stage, I choose the colors and begin the final artwork. The first version doesn’t always work-often, I have second thoughts, and an image can take weeks or even months to reach its final form.

You’ve worked with notable organizations like Terres des Hommes and MUSE. What role do you believe art plays in social causes and education?

Art plays a fundamental role in both education and social causes because it has an extraordinary power: it is not merely descriptive, nor does it provide a pre-narrated version of facts, but rather it opens the viewer’s eyes and mind. It has the ability to activate the observer, to make them see things from a new perspective one that is not predetermined but entirely personal.

Anyone looking at an image is inevitably compelled to interpret it, to bring something of their own to it, and in doing so, a cognitive process is set in motion that allows them to reconstruct the narrative of the circumstances they are living in. In this sense, art does not offer ready-made answers but instead creates space for reflection and awareness.

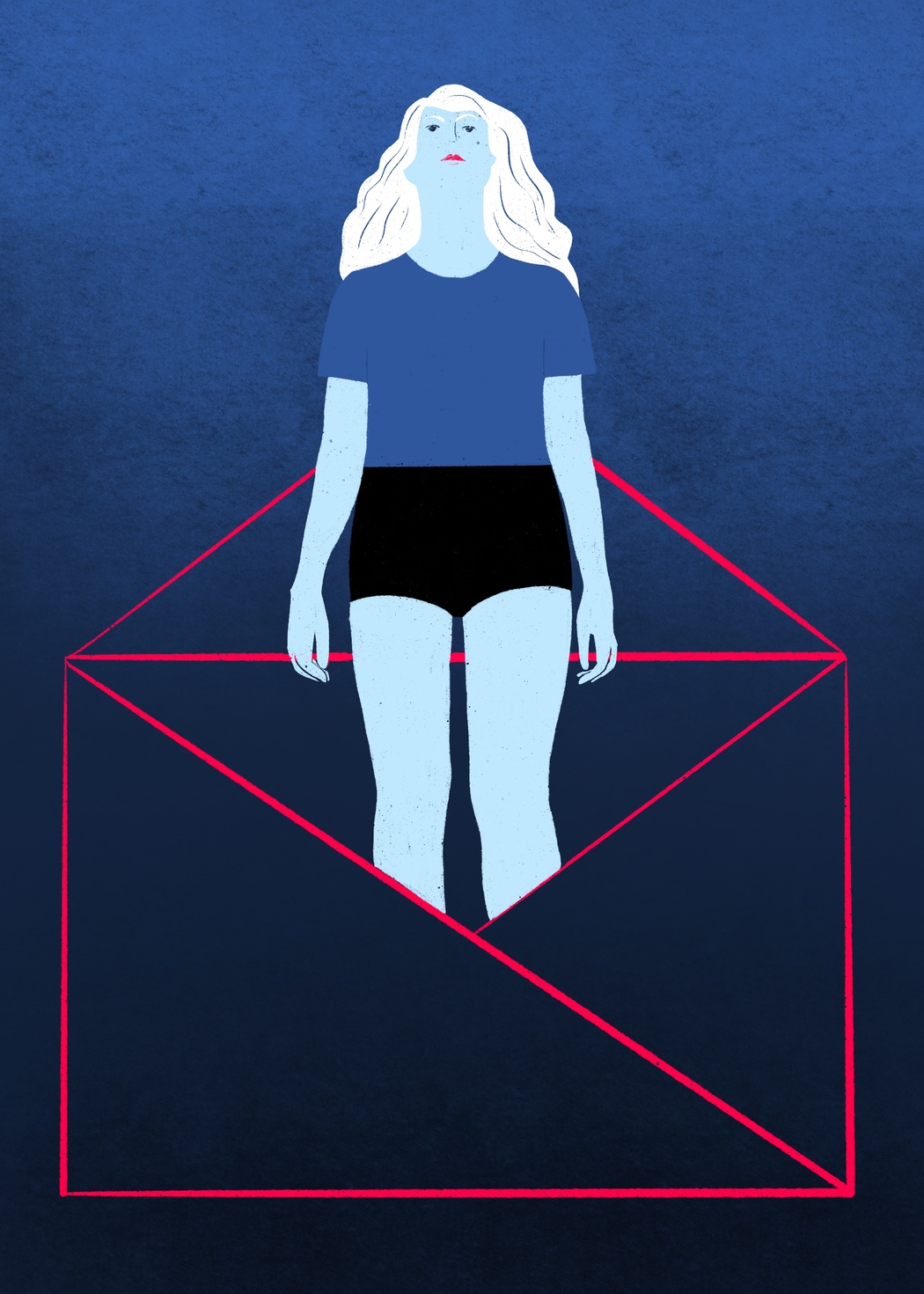

Michela Nanut | Fall | 2024

Michela Nanut | Fall | 2024What has been the most rewarding part of combining your work as a teacher and an illustrator?

Being an illustrator and being a teacher are very similar and complementary jobs. They have a lot in common, and often the skills required are essentially the same. In both cases, building relationships with others, the desire to communicate abstract concepts, and problem-solving are fundamental. Helping someone understand something and illustrating a concept are, in the end, two exercises in problem-solving.

Both are professions with a strong social vocation, as they require putting oneself out there in front of others and finding a balance between our own intentions, our identity, and the relationship with those who are watching or listening. Whether in illustration or teaching, you never work in a vacuum-it’s always a dialogue with the world.

Inclusion and social integration are central themes in your work. How do you think art can influence these issues on a larger scale?

Art has the power to give visibility to topics that have long been overshadowed by social stigma and prejudice. Through various forms of expression, it can offer new perspectives on inclusion issues, showcasing often marginalized realities in unexpected and innovative ways. This allows for the creation of new narratives that bring the world of disability and marginalization closer to something perceptibly beautiful, transforming the way these realities are perceived and experienced in society.

Looking back at your career, which project or piece of work are you most proud of, and why?

I am very proud to have participated in the migrant minors project, an initiative that gained great visibility, was highly appreciated, and still feels fresh and relevant even after years. In general, I am always very satisfied when I get to illustrate while collaborating with other professionals, sharing a common project, and bringing together different ideas and perspectives.

Working alone on my drawings is not for me. Of course, sometimes it’s relaxing, but the real challenge that excites me is engaging with others and sharing ideas. I like having a dialogue, discussing with people who help me see where I’m going wrong and guide me in the right direction.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.