Felicitas Yang

Where do you live: Paris, France

Your education: New York Film Academy; Los Angeles, US – Bachelor of Fine Arts, 2015–2016

New York Film Academy; New York, US – One Year Conservatory, 2014

Describe your art in three words: Temperate, perceptive, present

Your discipline: Photography and filmmaking

Website | Instagram

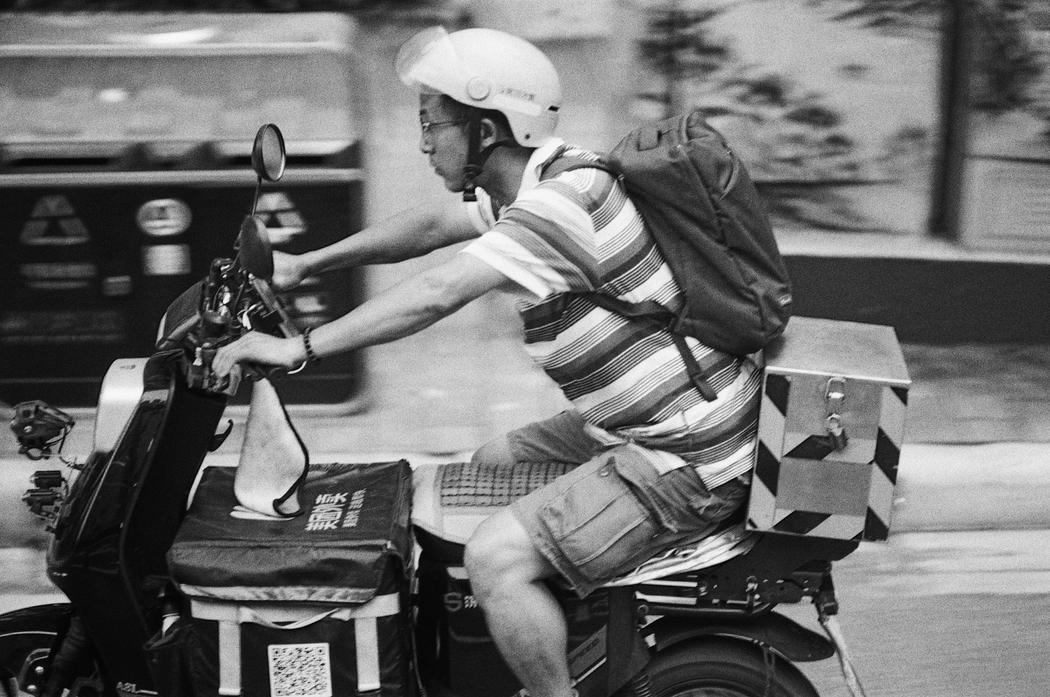

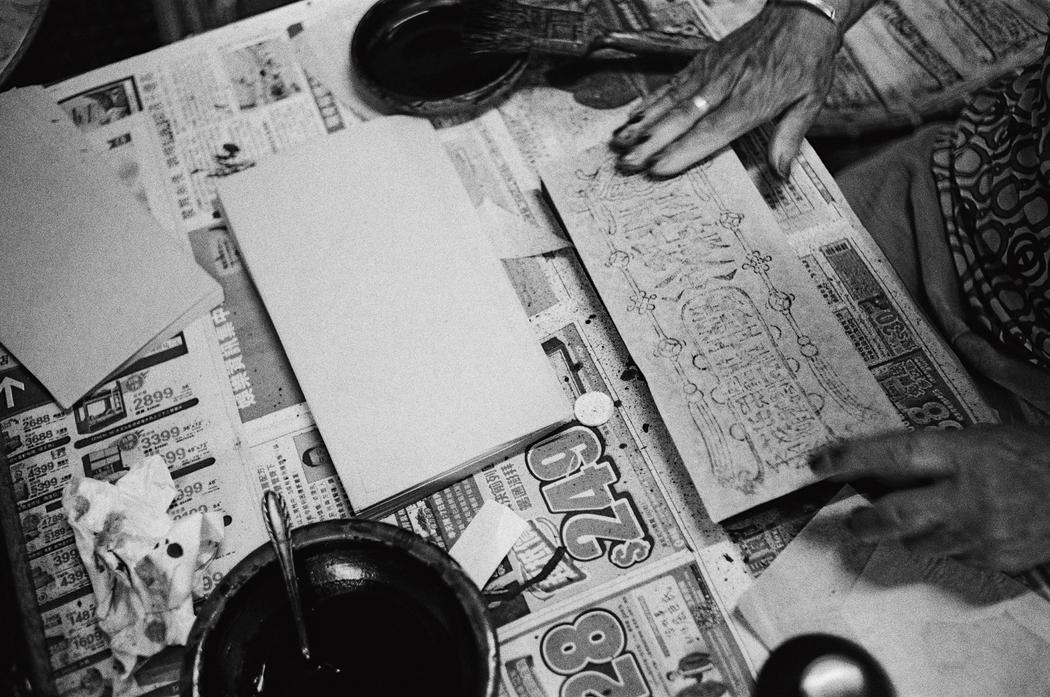

Felicitas Yang | Go-Between | 2025

Felicitas Yang | Go-Between | 2025

Growing up between Chinese and German cultures in Paris, how has this multicultural background shaped the way you observe and represent places through photography?

Anthropologist Ulf Hannerz describes cosmopolitanism in Cultural Complexity as more than the idea of existing beyond a single society or nation — it is a willingness to engage with the “Other.” I can intimately relate to this in the context I grew up in. It taught me that cultural identity is never fixed but fluid, and that every place contains multiple cultural interconnections. As a result, I developed a slightly distanced way of looking at things; that feeling of always being a little bit of an outsider never really left me.

There’s a part in The Keeper of Sheep by Fernando Pessoa that goes: “From my village I see as much as from earth one can see of the Universe… Therefore my village is as big as any other earth, because I am the size of what I see, and not the size of my own height…” Growing up in a place neither of my parents are from while juggling between languages is like living in a village of its own — a “floating village,” slightly removed from everything. Pessoa’s poem implies that reality is measured through one’s perception, which isn’t limited by physical constraints. It is like a limb: the more you stretch it, the farther it can reach.

Photography works the same way. It’s not about documenting any given subject as it is “supposed” to appear, but about observing it without assumptions. In that sense, the way I photograph places is intimately linked to my upbringing: I am always observing, never entirely inside, never entirely outside. There’s a word I really like: immanence (as opposed to transcendence). It refers to meaning and experience emerging from being fully present in the world, without looking to an external or transcendent notion — a kind of lucidity without metaphysical consolation. Photography can accept the world’s indifference and embrace it; it can show that the world is exactly enough and become a way to situate oneself perceptually and register what is present without projecting something beyond it.

Felicitas Yang | Go-Between | 2025

Felicitas Yang | Go-Between | 2025

You initially wanted to become a painter and later studied film directing. How does your cinematic education continue to influence your photographic practice today?

Watching movies, I became increasingly interested in the work of filmmakers who like to linger. Leaning into stillness and duration is a way to exercise our attention. I used to think that a moving camera automatically made an image more compelling. But with time, I’ve come to perceive most camera moves as superfluous, usually there to dazzle rather than serve the narrative. This gradual disinterest toward movement is, paradoxically, what developed my respect for photography. Its static nature asks something else of the viewer: you’re incited to study the image as opposed to letting yourself be entertained. In that sense, the relationship becomes more active. We allow for the majority of video content to happen to us; it’s an often passive relationship we turn to for comfort. Photographs, on the other hand, demand attention. Filmmakers like Chantal Akerman, Yasujiro Ozu, or Abbas Kiarostami resist the use of artifice in their work and explore a more sustained kind of attention.

Photography naturally contains this restraint: it can’t rely on movement, so it has to communicate through more subtle or conceptual means. Ultimately, I think all practices influence one another. Today, I still make short films with my partner, Armando Milano, and photography and film constantly inform one another. Film taught me how to look at photographs, and photography, in turn, has taught me how to think about time in film.

You work exclusively with analog photography. What does shooting on film allow you to express that digital photography does not?

Shooting on film is as much about principle as it is about expression. Analog demands an attentiveness and technical awareness that digital rarely does. More importantly, it keeps me from being greedy: I cannot rely on taking fifty shots to get one good image. Each choice must be deliberate. The process slows one down, which creates a tangible connection to the specific time and place of the photograph.

Choosing restraint over excess, slowness over speed, is my way of resisting what Paul Virilio calls dromocracy — the rule of speed. Virilio argues that modern life, accelerated by technology, constantly compresses our perception, making us more reactive than deliberative. Digital images contribute to this by erasing the subtle transitions between moments. The image appears all at once and skips the very passage of time that gives experiences their depth. This is the disappearance of duration. Analog, by contrast, ties the image to a physical process, allowing it to embody the lived experience. Jean Baudrillard’s analysis of Disneyland complements this idea: even neutral, transitional spaces — like the theme park’s parking lot — are absorbed into the spectacle and emptied of their mediating function: “You park outside, queue up inside, and are totally abandoned at the exit… inside, a whole range of gadgets magnetise the crowd into direct flows; outside, solitude is directed onto a single gadget: the automobile.” This idea of being abandoned at the exit illustrates how the “in-between” disappears because it’s made inconsequential.

Shooting on film is stating that you care about the parking lot. It allows me to reclaim that in-between, that passage of time and the breadth of perception. In that sense, using film can emphasize immanence because it creates a direct relation to the world, reminding us that the world exists prior to and independently of its representation.

Felicitas Yang | Go-Between | 2025

Felicitas Yang | Go-Between | 2025

In Go-Between, the project began after a seven-year absence and the loss of your grandmother. How did grief and time shape the way you approached photographing these places?

My grandmother passed away during COVID. Less than 48 hours following her passing, her body had been incinerated and her ashes sent home in the hands of my cousin, uncle, and aunt. Efficiency is not compatible with grieving. The day she passed, my father tried to hide how upset he was. To this day, he’s never expanded on the matter.

Since the pandemic robbed us of our capacity to mourn her, it charged a return with the weight of loss. This created a sense of urgency to record what was familiar in case it would disappear. The camera became an insurance of remembrance as well as a form of protection: the physical elements of the camera — the viewfinder, the mirror, the shutter, the lens — acting as filters and introducing a layer of separation that creates space for reflection.

Felicitas Yang | Go-Between | 2025

Felicitas Yang | Go-Between | 2025

Many of your images feel suspended between movement and stillness. How do you think about time when composing your photographs?

When composing an image, I’m constantly negotiating with time. How long am I exposing it for? When is the right moment to press the shutter? I used to work a lot as a focus puller. Time was always of the essence: you’re pulling focus alongside the actors’ movements. Taking photos with an analog camera is very similar. I love the challenge of photographing things in movement, notably events and dance performances. It’s silly, but getting an analog photograph of a moving subject in focus gives me a ridiculous sense of accomplishment.

From a less practical standpoint, I think of time as deeply subjective and reliant on each individual’s perception. That being said, modern life’s velocity will often come to destabilize the natural rhythms of our personal perception. In Science and Sanity, philosopher Alfred Korzybski observed a cognitive mismatch arising from the speed of technological advancements, saying that modern communication allows us to act faster than we can fully process. As a countermeasure, he proposed a type of semantic training designed to slow down mental processing to keep pace with reality.

Similarly, Paul Virilio argues that modern vision is no longer human vision but machine vision — that cameras, radar, satellites, and screens have come to replace direct perception (or immanence). The way media is presented on social platforms, for instance, is within spaces where time and attention are fully mediated and vision is commodified. As a photographer, I’m implicated in that system but feel the need to resist it. I like to think about my practice as using images to resist the regime of images.

Felicitas Yang | Go-Between | 2025

Felicitas Yang | Go-Between | 2025

You often use telephoto lenses to isolate details and blur context. What draws you to this visual strategy, and how does it relate to memory and perception?

I used long lenses a lot in the past, specifically for series like Windsong or I Wanted to Call but Nobody Answered. Our perception shapes our memory, and we often remember very specific details that may seem insignificant to others. A long lens doesn’t just isolate details; it compresses space and channels focus. This allows a subject to appear bigger and amplifies its importance. For this series, however, I changed my approach by using (but not exclusively) wide lenses. This was to see more of the spaces — there was this underlying notion for me that the camera would allow me to revisit memories of things that were likely to disappear the next time I’d be there.

Human perception is deceptively fallible, which is why I feel as though I can rely on my camera to “set the record straight.” Photos will often show us more or something different from what we initially thought we saw. This is why I believe that taking a photo is inseparable from the process of selection. It’s an additional filter that allows me to reassert my intent as an artist. I’m cautious discussing photographers whose selections weren’t their own — like Vivian Maier, whose photos were published and sold without her consent, removing her narrative control.

For me, the selection process is what Owen Knowles calls a “re-entry into past experience.” In his introduction to Joseph Conrad’s Congo Diary, Knowles observes that literature is an imaginative re-engagement with the past to pursue a more impersonal but human truth. In photography, the delay between shooting and reviewing creates the same re-engagement and thus allows for insight and deliberation. The act of looking and then selecting from what we’ve perceived is where agency emerges and where choices really matter.

Felicitas Yang | Go-Between | 2025

Felicitas Yang | Go-Between | 2025

Returning to a place that no longer matches one’s memory can be disorienting. Did the act of photographing help you reconnect, or did it emphasize the distance you felt?

It did both. Photographing helped me process the experience, but it could also act as a barrier between myself and what I was looking at. The camera can be a distraction, at times an obstacle. Photographing can be aggressive because of its intrusive nature. But it can also be gentle. I feel as though we don’t focus enough on the kindness that can ensue from someone else’s viewpoint. I believe that if a photographer has love in their heart, it will seep through. Chantal Akerman, for instance, has a very kind eye. She pays attention to what is easily ignored and lingers generously. Her work suggests that attention itself can be a form of care. In her memoir, My Mother Laughs, she writes: “I listen to her laugh. She laughs over nothing. But this nothing means a lot.” The “nothing” is everything. Attention becomes a doorway to empathy, and truly looking at something requires patience and respect, which can contribute to expanding one’s sensibilities.

Carl Jung speaks of “individuation,” integrating opposing parts of oneself to reach internal coherence (or peace). A camera can direct attention, both outward (toward the subject) and inward (at oneself). For this particular project, it became a compass to navigate my emotions and anchor myself to the places and people I encountered, to ground and situate myself in the world, and assert my position in regard to the past.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.