Lærke Helene Askholm

Where do you live: Copenhagen

Your education: MSSc in Social Work, BA in International Business Communication

Describe your art in three words: Alive, Reflective, Sensitive

Your discipline: I’m a self-taught illustrator with a foundation in traditional drawing, and I also create drawings as independent artworks. In addition, I am a writer and singer.

Portrait of Lærke Helene by Luca Berti

Portrait of Lærke Helene by Luca Berti

You began drawing very early and then paused for many years. What made you return specifically to analog drawing, and why did it feel like the right moment?

I had missed drawing for all these years, and when I finally received acceptance by a publisher for my second children’s book, I thought it was obvious that I should illustrate it myself. My first children’s book as a writer (published in 2023) had a fantastic illustrator, Lilian Brøgger, for whom I am very grateful. Back then, I was also unsure how well I could draw, since it had been so long. But with the second book, it was as if I had simply made the decision. I thought that even if it took time, it had to be in my hands, thoughts, and eyes all the same. And then I discovered that it was right there inside me, just waiting to come out on paper, once I started.

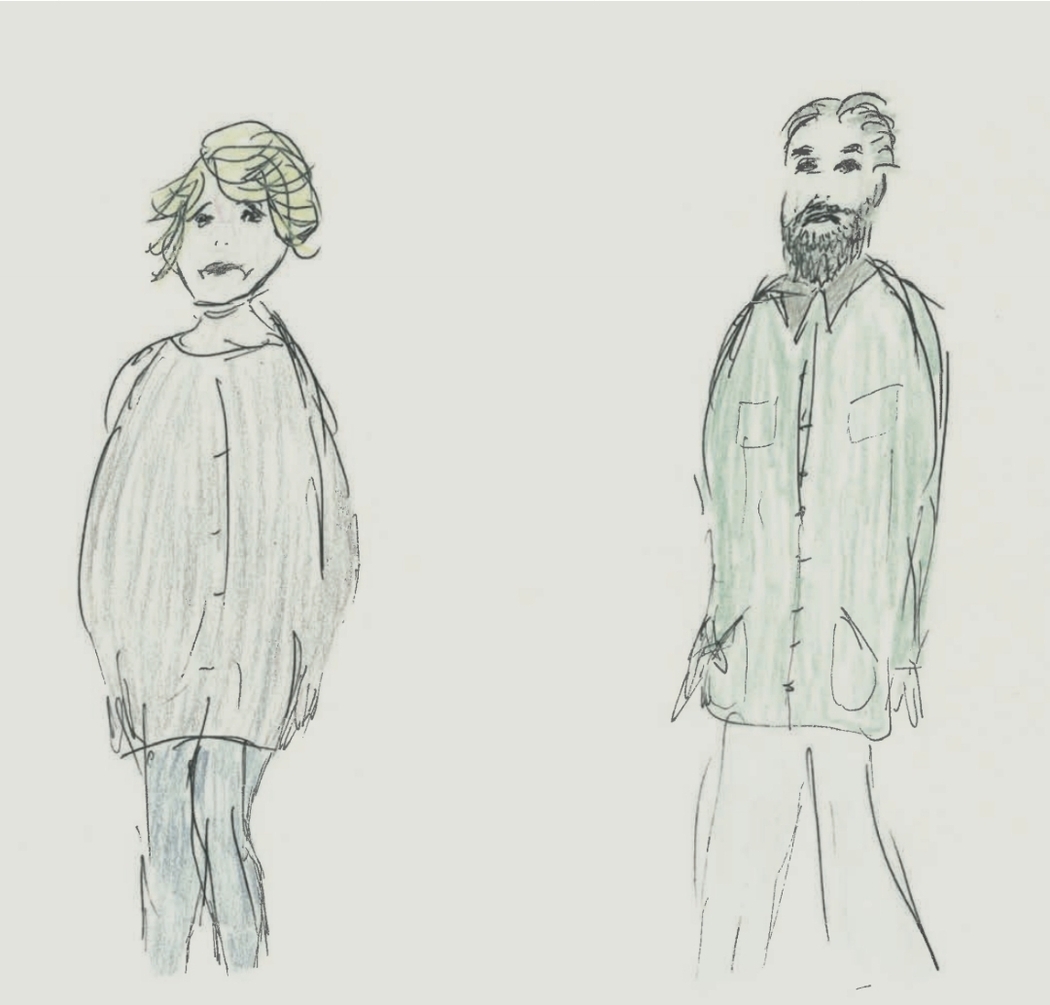

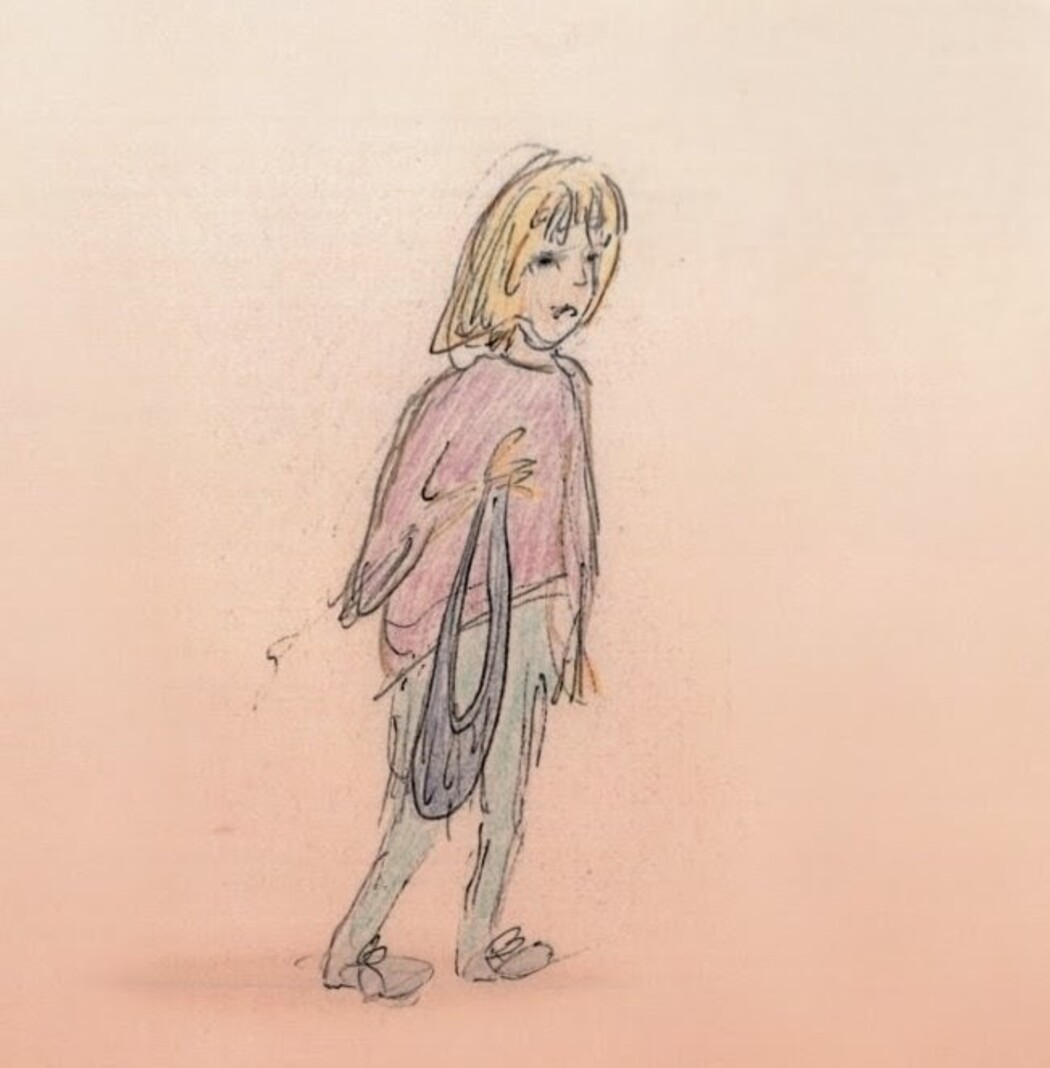

Your book My Own Truth is told through a child’s perspective within family conflict. Why was it important for you to let the child’s inner world lead the narrative visually?

Both the text and the drawings are from a child’s perspective, and the visual aspect can be a very important part to include in stories, because it, like music, shows something that doesn’t always have words. Therefore, the drawings strengthen the text, which is not extensive, as each page contains few words and simple, expressive drawings that one can either talk about or reflect on further. Some children may also feel inspired to draw themselves. The simplicity is important, as it gives the children reading the book the opportunity to fill in what they feel suits them – what they can relate to and perhaps feel understood and inspired by. A book can provide hope in difficult situations if one is met in their own perspective, so they don’t feel completely alone with their feelings.

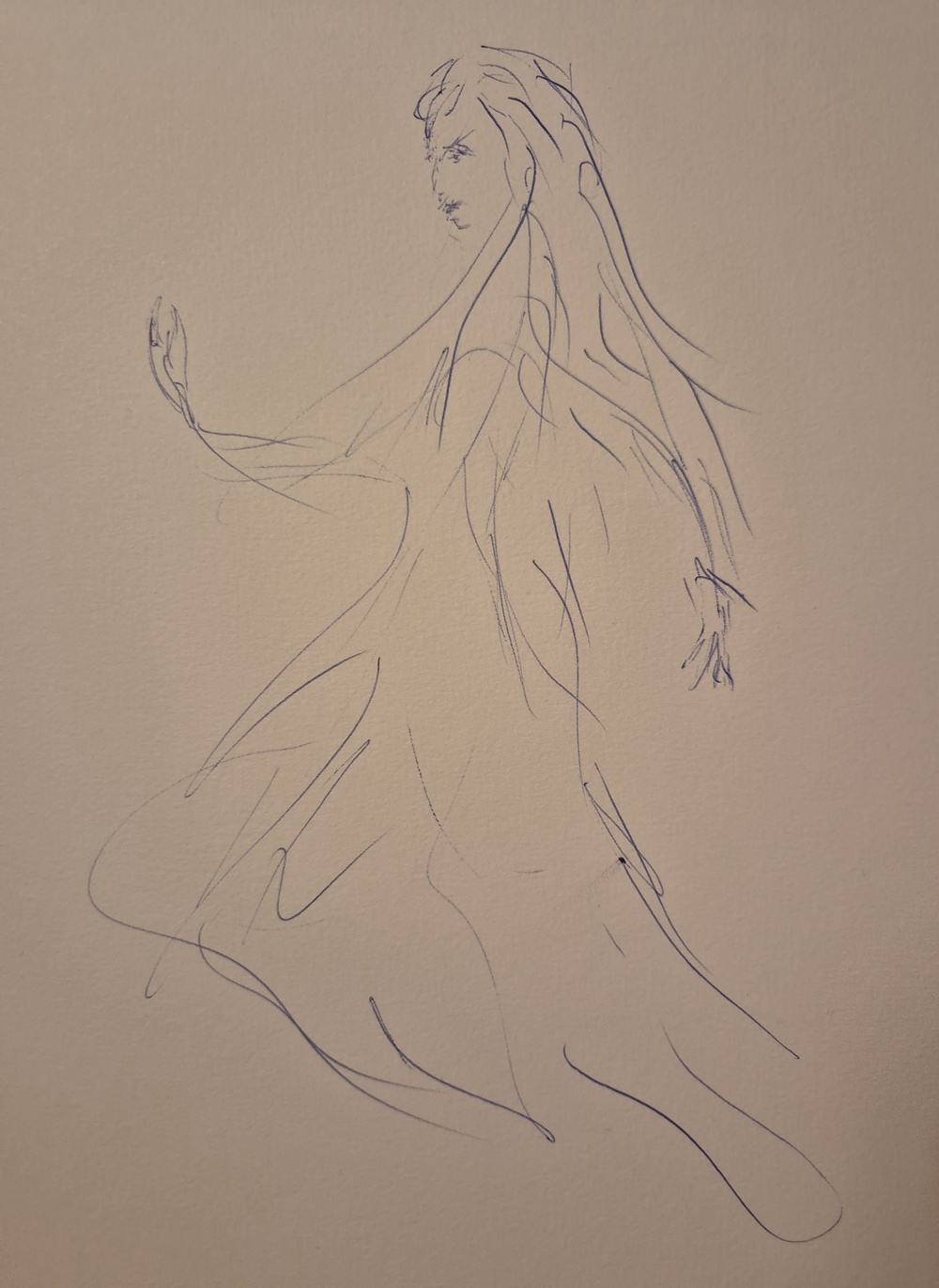

Your illustrations feel restrained yet emotionally charged. How do you decide what not to draw, what to leave open or unfinished?

I try to capture the inner feeling, and it can be very introspective—sometimes it’s a character that doesn’t have much movement or many outward features, but whose gaze is strong, and where a few elements hint at what is at play. It’s about communicating something profound without too much filler. The filler is created by the gaze that meets the illustrations and senses something, and I want to give space for that, so I don’t put everything in a closed frame. A sketch line can be stronger than a meticulously colored illustration with many elements. I have ruined very simple drawings either by over-coloring or by adding too much background. I do like simplicity, but when it comes to color, I am also open to experimenting with different materials.

You work with fast sketches and a high working speed. What does speed give you emotionally or intuitively that slower processes might not?

When I don’t overthink and just draw—preferably quickly, letting my subconscious take over a bit—it becomes much more alive than if I fuss over it in the main line of a sketch. My line can sense if I’m thinking too much while drawing, and then it can end up looking strained. Something happens when you let the line run free, because details and expressions appear that you couldn’t have figured out beforehand, and you can continue to develop them with the line. When it comes to adding color, it’s fine to take more time, but speed really does something to a line’s expression, especially when it comes to living beings. Animals and people come alive in a different way. Backgrounds, objects, and buildings I can shade in a slightly quieter and calmer manner. My great-grandfather, Frode Lund (1900–1980), was an artist who illustrated many landscapes and old buildings, and I think that as a child I absorbed some of his drawing style because my grandmother showed me many of his works. I have several of his originals, as well as his published book, which contains 455 illustrations.

Many of your figures appear slightly fragile, as if caught mid-gesture or mid-thought. Are you more interested in moments of action or moments of inner stillness?

That’s a very good question, because I think of action as something that is not limited to physical movement, so that’s why I would not be able to choose. A figure can be in action even when it is still, if something is happening inwardly—such as reflection, emotion, or inner tension and that is what I try to capture. Both forms of action, the inward and the outward, contain something visually and emotionally compelling that can be captured in a figure. This is what makes these moments so exciting to work with, as they often hold many layers of emotion, even without dramatic movement.

After undergoing surgery on both hands, choosing to illustrate an entire book must have been a profound decision. Did this experience change your relationship with drawing or your body?

The time I had surgery on both hands, in May 2024, could easily have been a moment when it made sense to give up on ever drawing again. At that time, I wouldn’t have believed I could ever do it again either. There were many stitches in both hands, and both index fingers were cut open and sewn back together. I had to start over using those fingers, and the rehabilitation took a very long time. On top of that, I have lost some sensation in them. Instead of giving up completely, I suddenly felt motivated to draw again. In a way, I insisted on it, and I don’t really know why—but perhaps this is how adversity can make us defiant and encourage us to try to make the best of the worst through creativity. It has undoubtedly been good for the continued rehabilitation of my fine motor skills.

Having lived many years in southern Spain, how has Spanish culture, color, or everyday life influenced your visual language?

Flamenco is about expressing emotions through words, music, and dance, and it is a form of poetry and expression that is a significant part of southern Spain, Andalusia. In my view, there is no doubt that their daily connection to emotions through this poetry is an incredibly healthy element, something you simply do not find in the same way in northern Europe, where there is a greater distance. The contact with, and respect for, the right of emotions to be felt is very comforting and inspiring for me, both personally and artistically. In the visual arts, I love to draw the intimate, the calm, and the intense from Andalusia. It makes me want to express myself creatively and encourages me to feel more deeply—even when I am drawing other subjects.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.