Phillip Staffa

Photo By Karsten Boysen

Photo By Karsten Boysen

Your sculptural works often transform everyday objects into contemporary totems. What draws you to these familiar forms, and how do you choose which objects to reinterpret?

The subjects choose me, not the other way around. I move through the city with my radar open, and certain forms just stay with me—days, weeks, sometimes years. Most ideas hit in transit: between places, overheard lines, tiny moments. They need time to shift until I see them clearly. The cigarette sculpture, for example—I carried the thought for ages, but the spark came in a bar in France, looking by chance at the twisted butts in an ashtray. That moment the idea shifted into a realm of the tangible, something I knew I could give an outer form to. I know I’ve hit something when my blood rushes a little and the idea opens up into into a path with possibilities, not a dead-end result.

Phillip Staffa | Candy (Silver Blue)

Phillip Staffa | Candy (Silver Blue)

Many of your pieces play with scale, material shifts, and glossy or reflective surfaces. What role does transformation play in your artistic process?

An idea needs material to manifest. Transformation is an integral part of the idea itself. Changing scale or material breaks the object open and gives me distance. It lets me see the idea fresh, evaluate it, and push it further. Materials are not just tools—they’re filters that force me to rethink the original impulse. And yes, I’m drawn to glossy and reflective surfaces. They pull the viewer in, throw their own image back at them, and turn the object into something alive and interactive. A reflective surface is never still — it’s open, and transforming with the world around it.

Phillip Staffa | Cigarette Butt

Phillip Staffa | Cigarette Butt

Your pieces—oversized candy, cigarette butts, melting ice cream, inflated lips—balance humor and critique. How do you navigate the tension between playfulness and deeper commentary?

I love joy, and I love approaching life playfully—it makes things easier to digest. But I am also wired for overthinking, obsessed with concepts. I need both, and my works need to nourish both sides. If something only satisfies the playful impulse or only the intellectual one, it usually falls away over time. In that tension the idea becomes three-dimensional for me; it grows axes in all directions.

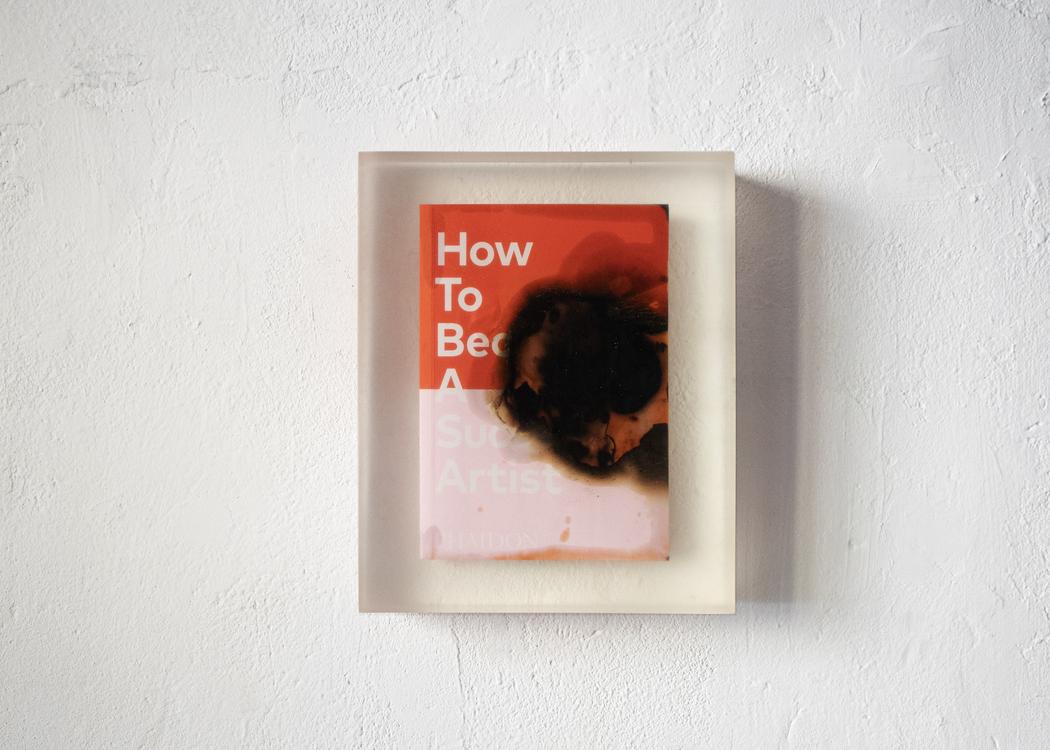

Phillip Staffa | Successful Artist

Phillip Staffa | Successful Artist

Coming from a background in music, how does compositional thinking influence the way you construct or arrange sculptural forms?

Music for me is rhythm, form, colour, improvisation, ritual, freedom – essentially everything I care about in sculpture. I spent years studying proportion, structure, articulation—so these things root deeply in my thinking. I don’t consciously apply them, but they shape how I build and arrange things. They’re there, like a second skin.

Several pieces capture traces of urban life: worn objects, discarded materials, playful re-creations. What relationship does your work have with Berlin and its visual language? My collecting practice is rooted in the streets—especially Berlin. I walk into these contrasts and tiny abysses every day: beauty, decay, humour, waste, disgust, life. Berlin throws objects and situations at you constantly. It’s a visual language that’s raw, direct and unfiltered, and it feeds my work in the most honest way.

Phillip Staffa | Dropped Cone (Pink Cherries)

Phillip Staffa | Dropped Cone (Pink Cherries)

Collaboration is central in your process, especially with MONAS Collective. How does working with musicians, scientists, or researchers expand your artistic language?

Collaboration is how I learned creativity. After 25 years in music, I’ve often experienced how a group can arrive somewhere none of us would have reached alone. I’m lucky to have people around me whose thoughts inspire and challenge me. That exchange fuels my work. At the same time, I’ve discovered a new beauty in working alone—thinking things through, finishing a piece without relying on anyone. It’s again a balance.

Phillip Staffa | Lips (Fiesta Red)

Phillip Staffa | Lips (Fiesta Red)

Your practice revolves around transformation and perception. What shifts do you hope occur in viewers when they encounter your work?

I love when there’s a physical reaction—laughter, surprise, a sound, a sudden stop. In my old studio in Berlin Neukölln I often worked on the pavement, and people constantly stopped to engage, observed, commented, asked questions. Kids pointed at things, older people marveled or disliked what I was making. Those encounters meant a lot to me. Once a child walked past a freshly painted dropped-cone sculpture, looked at it, and instinctively said: “Yummy.” If a work can trigger something that immediate, I’m happy.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.