Xingyun Wang

Photo By Yuhan Hu

Photo By Yuhan Hu

You describe paper as both delicate and resilient — a metaphor for memory and endurance. How did you arrive at this relationship between material and meaning?

This connection really grew out of the process of making. When I first started working with paper, it was mostly a practical choice — it’s flexible, lightweight, and easier to carry than canvas, especially since I was often moving between spaces. But the more I worked with it and began researching its material history and cultural connotations, the more it felt like a natural medium for me.

Paper is incredibly varied — it can be thin like mulberry paper, or thick like bamboo paper. Each type holds pigment differently, and when I layer and sand them, the fibers begin to behave in unexpected ways, revealing strange textures and forms. These physical transformations became central to how I think about memory and endurance — how something so fragile can also carry so much history, hold marks, scars, and still remain intact.

Conceptually, paper is porous — it absorbs, conceals, reveals. It can be torn, cut, stained, and yet it persists. That resilience mirrors the kind of emotional and psychological terrain I try to explore in my work. So over time, paper stopped being just a surface to work on and became an active collaborator in the process.

Many of your works carry the tension of destruction and repair — tearing, sanding, layering. Do you see this as a healing act, or more as a documentation of damage?

I see this tension as holding both. It’s a record of damage and a gesture toward healing. These two states aren’t separate or linear; they overlap, recur, and inform each other. That dynamic mirrors my personal experiences. The act of tearing or sanding can feel violent, but it’s also a necessary part of transformation —revealing what’s underneath, making space for something new. Layering, then, becomes a way to hold those histories together. I don’t see repair as a clean resolution, but as an ongoing process that acknowledges what was broken without erasing it.

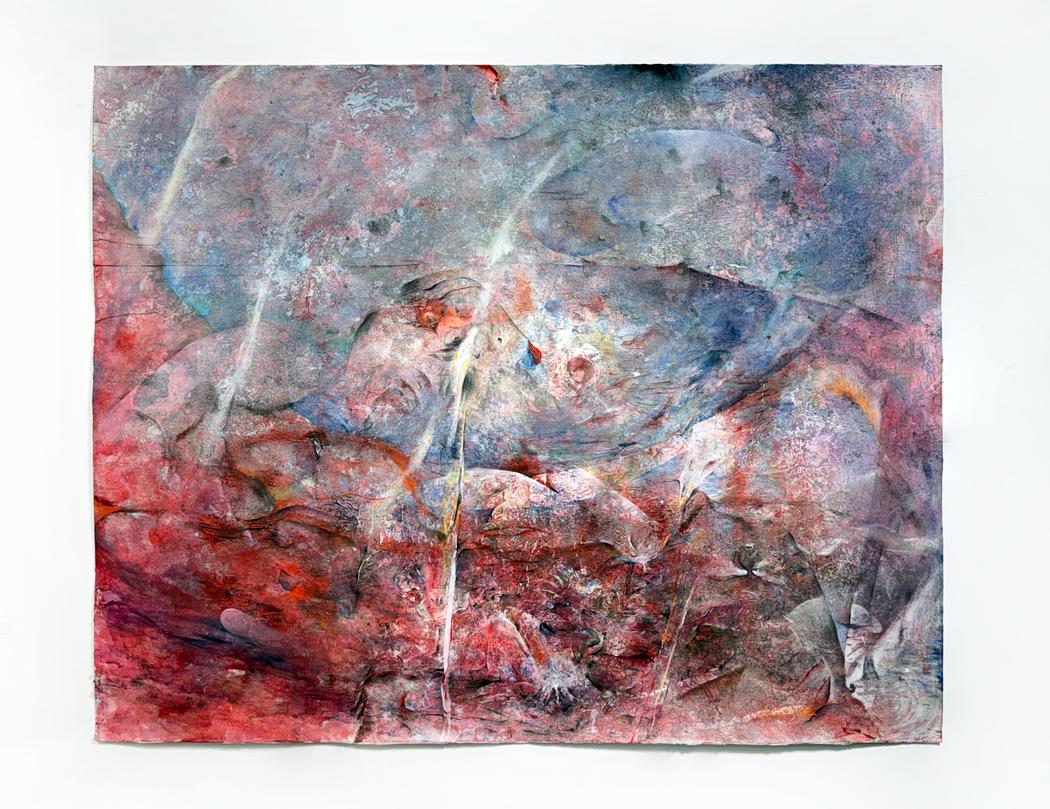

Xingyun Wang | A Third Eye | 2025

Xingyun Wang | A Third Eye | 2025

The presence of embedded materials like hair, glass, and perforations adds a visceral intimacy to your surfaces. How do you decide what to include in each work?

I usually select my materials and palette before starting a piece. Because I make my own pigmented glue, I have to prepare it a day in advance, which gives me time to consider which pigments and materials like sand, glass flakes, pumice, or hair that I want to include. This preparatory phase is slow and deliberate, and those decisions are often meditated during that time.

That said, I also leave space for spontaneity. Sometimes, during the making process, I’m carried by intuition and introduce unexpected materials. This can lead to results I didn’t plan for—unwanted textures or surface disruptions— but those imperfections often become the most compelling parts of the piece. They carry their own logic and energy, and I try to remain open to what the material is asking for in the moment.

Xingyun Wang | Dwelling Places | 2025

Xingyun Wang | Dwelling Places | 2025

Your process of working on the floor and manipulating wet paper feels very physical. How important is the role of the body in your artistic practice?

Bodily engagement is central to my practice. There’s a performative aspect to the making process that doesn’t always translate directly into the finished painting, but its traces remain. You can often find fingerprints, footprints, scratches on the paper surface, or areas of paint shaped by gravity when the paper was lying flat. These marks record the interaction between my body and the material.

I’m interested in how these physical traces capture time — the duration of making, the movement of the body, the effect of the environment. The painting becomes a document of its own making, holding a quiet history of those interactions. Working on the floor allows me to approach the work from all sides. I don’t see the paper as a passive surface, but as something I move with, press into, and respond to. That intimacy and physical exchange is something I find both grounding and conceptually important.

Xingyun Wang | Ashes Unspoken | 2024

Xingyun Wang | Ashes Unspoken | 2024

The red and burnt tones in your series suggest both danger and vitality. What emotional or psychological states do these colors evoke for you?

Red evokes many things for me—passion, erosion, destruction, and a persistent sense of urgency. Whatever the specific association, the intensity of the color is always at its peak. That’s why I’m drawn to this palette. It holds a wide range of emotional intonations, yet all of them feel powerfully charged. The burnt tones deepen this atmosphere, suggesting traces of something that has endured fire or heat, something damaged but still present. Together, these colors create a psychological landscape where danger, vitality, and warmth coexist, amplifying the tension I want the viewer to feel.

Your compositions suggest multiple viewpoints — as if seen through fractured lenses. Do you think of your works as landscapes, memories, or psychological spaces?

I think of them as an in-between space—somewhere between the body and the landscape. At the same time, I’m drawn to the idea of psychological space, and I welcome that interpretation.

The viewing logic of Chinese handscroll paintings has been a major influence on me. In those works, perspective isn’t fixed—it moves fluidly, unfolds with time, and shifts as the viewer moves. I try to bring that same sense of unstable, shifting perspective into my work.

I use large, sweeping gestures with pigmented glue, and then build up the surface with small, intricate marks. I want the viewer to have a dynamic experience—stepping close to trace the fine terraces of a landscape, then pulling back to see an atmosphere emerge, a body-like form inhabiting the space. The multiplicity of viewpoints, like fragments through shifting lenses, allows the work to live between scales and states: landscape, memory, body, and dream.

Xingyun Wang | Cast | 2024

Xingyun Wang | Cast | 2024

How do you navigate between intuition and control in your creative process?

I deeply value intuition in my process, but it must be grounded in control and a clear understanding of the material. That balance allows me to work freely without feeling lost.

I spend a lot of time preparing before I begin painting. I make pigmented glue from scratch each time, drawing from a few formulas I’ve developed and refined over the years. I adjust them depending on the needs of each piece, sometimes changing the density, pigment ratio, or drying time.

When I’m not actively painting, I research different kinds of paper and test how various pigments behave across layers and surfaces. Each paper has its own absorbency and texture, and I experiment with how they respond to sanding, layering, or staining. These preparations give me the confidence to work intuitively. When I begin applying glue and paper, I’m able to trust my instincts because I’ve already done the groundwork. That’s how I navigate between letting go and staying in control—by building a foundation that supports improvisation.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.