Sofía Ibargüengoitia

Where do you live: Mexico City

Your education: Theater, Architecture, and Painting

Describe your art in three words: Oneiric · Ironic · Uncomfortable

Your discipline: Painting

Your latest project “Don’t follow me, I’m also lost” merges theater and painting into a single narrative experience. How did the idea of blending these two worlds first appear to you?

The idea came up from identifying in my own practice the need for a change of paradigm in the way I conceive painting, to experiment with interdiscipline as a way to observe the blind spots that exist in traditional painting and transform artistic practice into a more expansive experience, not only for the artist but also for the audience.

Throughout my career I have trained in theater, music, architecture and painting; so the fusion between these disciplines seemed like a natural process to me. Theater as a language through dialogues, situations and characters creates a fictional world where everything is possible, therefore, it opens the door to the exploration of the different levels of human experience: physical, intellectual, sensory, emotional, symbolic, narrative, imaginative and spiritual.

Through theatrical language I wanted to create a fictional space that would serve as a container to expand the creative process of painting that would allow me to explore deeper layers of my own work.

Sofía Ibargüengoitia | A Dintinguised Gentleman | 2025

Sofía Ibargüengoitia | A Dintinguised Gentleman | 2025

When developing the play and the paintings simultaneously, how did one influence the other? Did certain scenes emerge from specific visual ideas or vice versa?

By developing both things simultaneously I would consider them as a single work; it was a process of four years where sometimes a shape or a color triggered a dialogue or a character, and sometimes a scene made me understand what was happening in the painting. At other times, paintings emerged from a lived experience translated into theater or transformed those that were already there.

It also happened making a painting or writting a dialogue intuitively where it seemed that it did not make sense with the rest of the works and a year later the relationship between them was revealed, as if the information had been there to be discovered later.

You don’t need the play to understand the paintings nor the paintings to perform the play, yet together they take on multidimensional meanings.

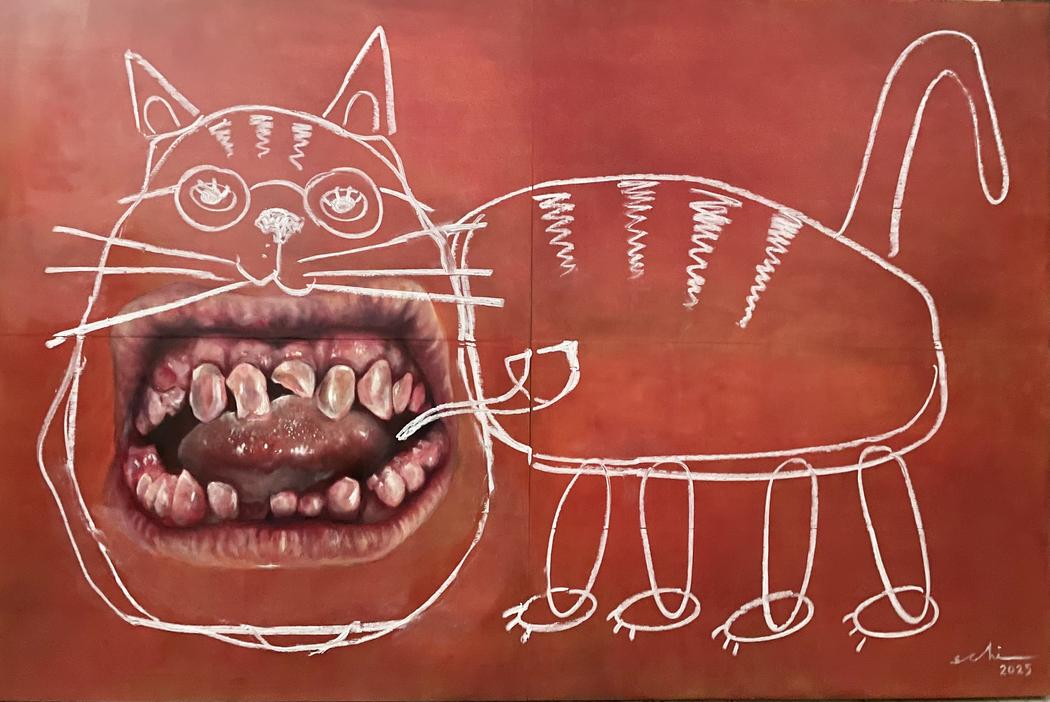

Sofía Ibargüengoitia | I Like To Be Bitten | 2025

Sofía Ibargüengoitia | I Like To Be Bitten | 2025

Many of your paintings explore the human body in raw, almost uncomfortable intimacy. What draws you to this physical and emotional exposure?

The history of the nude in art, especially the female nude, has had a perspective of the body as an object of desire of the observer; traditional beauty values have dictated the way the body is represented in painting. However, I find more interesting the perspective of the body as the materialization of the human experience in all its complexity.

Influenced by the work of Jenny Saville and Lucien Freud, I seek to explore the aesthetics of the body that emerges from pain, the grotesque, sadness, bonds, illness and mystery where, through the distortion of perspective or the use of “tragic” color palettes, it becomes possible to delve into the contradiction of human nature expressed in the body.

Humor and absurdity seem to coexist with existential tension in your works — for instance, the cat with human teeth or figures emerging from surreal contexts. How do you balance irony and seriousness?

I think there is nothing more serious than humor. By combining elements that apparently cannot coexist, it disconcerts the observer and confusion always forces us to ask questions. Humor, by proposing another order of things, questions them.

Sofía Ibargüengoitia | Margarita | 2025

Sofía Ibargüengoitia | Margarita | 2025

The theatrical aspect of your exhibition involves sound, light, and movement. How does this multisensory approach change the audience’s perception compared to traditional painting exhibitions?

One of the main interests in changing a traditional painting exhibition for a theatrical performance, was precisely to be able to share with the public not only the final result of a pictorial work, but to invite them into the creative universe that surrounded it.

When I finished writing the play and the paintings, a period of collaborative work arose with the stage director, the producer, the costume designer, the actors and all the people involved in a theatrical production to bring to life another phase of the project, where the visions of all those involved enriched the artistic experience.

The result of this proposal made the public emotionally involved with the works and for the time of the theatrical performance the attention was completely on the artistic experience, unlike traditional exhibitions where the public is generally distracted and the curatorship does not necessarily get the viewer involved with the works.

In several works, you seem to reinterpret cultural or art-historical icons — such as the inscription “R. Mutt 1917” referencing Duchamp. What role does art history play in your creative dialogue?

I am particularly interested in the elements that throughout the history of painting, sculpture, cinema, music, architecture and literature have become cultural references. It strikes me how something can acquire a common meaning for an entire community and become a symbol.

The cultural references that have meant something to me throughout my work, whether because they attract me or because I question them, I reinterpret them as a way of connecting with the rest of the people and playing with the meanings of the symbols. For example, some characters in the play were taken directly from Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland with completely different personalities than those that appear in the book.

Sofía Ibargüengoitia | The Hatter | 2025

Sofía Ibargüengoitia | The Hatter | 2025

Could you tell us more about the title “Don’t follow me, I’m also lost” — what kind of emotional or philosophical statement does it represent for you?

The title is an analogy of the creative process; an unknown territory in which, if you decide to walk through, you have to do it without a map. Because getting lost is the only way to actually find yourself.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.