Daria Sinaiskaia

Where do you live: Moscow, Russia

Your education: A professional degree in writing from the Gorky Literary Institute, complemented by studies in photography and contemporary art.

Describe your art in three words: Memory · Intimacy · Connection

Your discipline: Visual Art and Writing

Website | Instagram

“After Her” began as a deeply personal response to your grandmother’s passing. Can you describe the moment when you realized that photographing her belongings was becoming an artistic project rather than just a way to cope with loss?

It happened when I started sharing my first photographs with other people in the photography world. First, they were my fellow students in the online photography course from Michigan State University. Then, my first photography teacher and my friend, the layout designer Yana Rodina, helped me work more on the composition of the photographs. We met to discuss them, and for me, her feedback was incredibly important. It was my first photography project, so I was not confident in my skills and learned a lot while doing it. When the series was complete, she also designed the photobook, which became the final form of the project.

I am still grateful to the other people who helped me understand that what I do resonates with others—that it is more than simply documenting objects for my family and my own memory, but an artistic project. They supported me until I finished it, and I think without that support, finishing my first project would have been very difficult or even impossible.

Daria Sinaiskaia | Table | 2022

Daria Sinaiskaia | Table | 2022

How did your emotional state during that time influence the way you framed or composed the photographs?

Those objects were very important to me. With my photographs, I wanted to express what I saw in them – a concentration of grief, the feeling of missing my grandmother, and memory. The composition is mostly simple – I placed most of the objects in the centre of the image, which gives them a significant visual weight. The way I composed my photographs may seem almost too simple, but I couldn’t imagine composing them differently.

I took the photographs mostly at night, using a long exposure. I enjoyed the dim night light and the silence. It was like a silent dialogue between me and those objects, as if they were telling me their stories in the quiet, while the rest of the world was asleep.

Daria Sinaiskaia | Sewing Machine | 2023

Daria Sinaiskaia | Sewing Machine | 2023

Were there specific objects that were especially difficult to part with — or to photograph — and why?

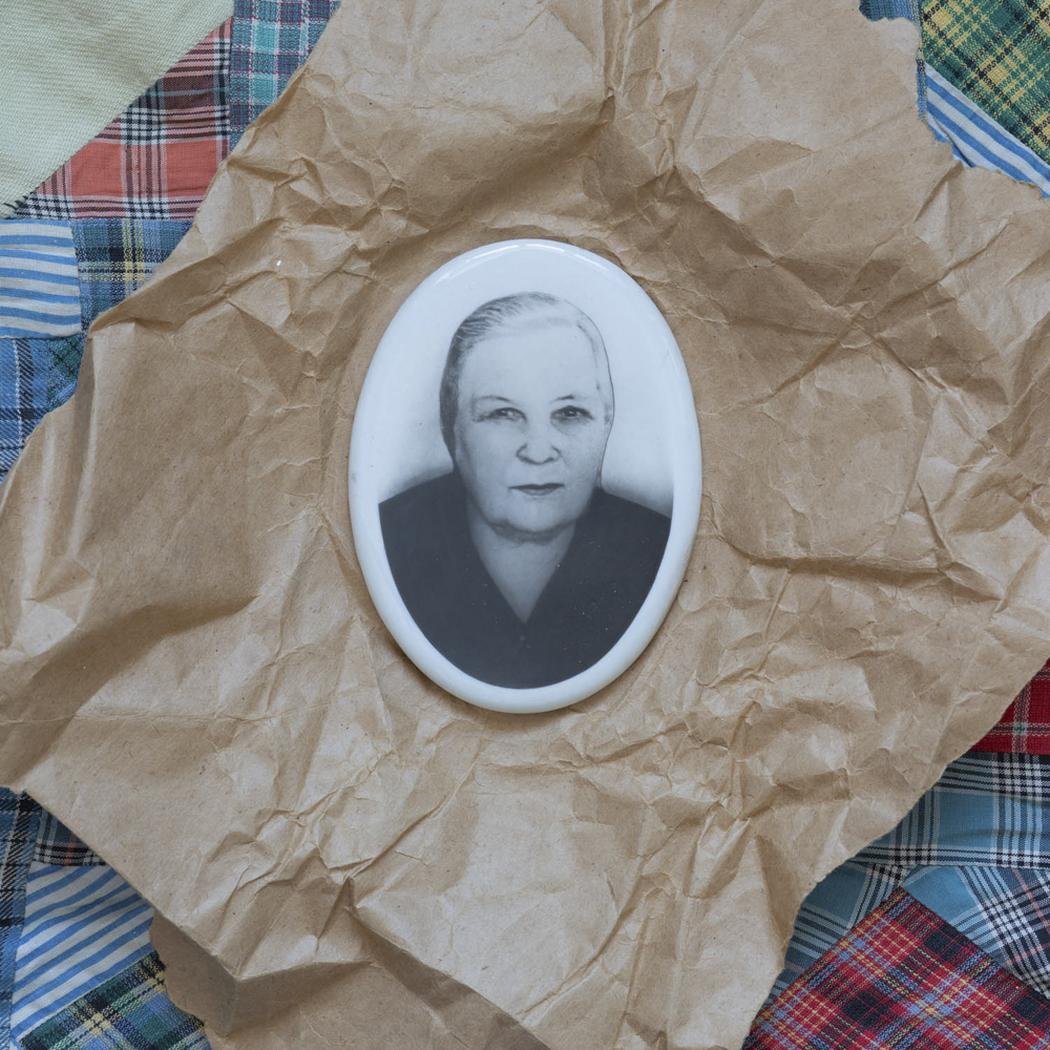

I would say I still haven’t parted with most of the objects. The small ones – like the portrait, some photographs and cards – are easy to keep, and I don’t think I will ever part with them. But it seems to be an issue for me to part even with bigger objects, like the table. After taking many photographs of it, I started appreciating its beauty more and now I can’t imagine throwing it away. My teenage children often make harmless jokes about how our kitchen looks: ‘Mum, you promised to keep it only for your project, but it seems you finished it, so what now?’

Our kitchen still looks the same. I call it my ‘Time Machine’.

How do you see the relationship between photography and memory — does the camera preserve, reinterpret, or even distort remembrance?

I think photography preserves, reinterprets, and distorts memory all at the same time. Even though I started with a wish to only preserve my memory, I found myself reinterpreting stories and narratives in the process. This project tells a story, and I am sure that in the process of storytelling, there is always some distortion—especially when I want to tell a good, understandable story with a clear plot.

Daria Sinaiskaia | Portrait | 2021

Daria Sinaiskaia | Portrait | 2021

You mentioned that each photograph is accompanied by a written story. How did you balance the visual and textual aspects — do they complete each other, or can each stand alone?

I believe the stories give more depth and significance to the images. My wish to write them was driven first by a simple thought: I know why each object is precious to me and the story behind it, but someone else—my children, for instance (I imagined them as my first viewers)—who sees it, often does not.

In the project ‘After Her,’ I wrote only what was needed to understand the stories behind the images. I think they complete each other. The part of the project about the beauty of the objects is told by the images, and the part about family history—my grandmother’s life, first of all —is told by the written texts.

All the stories are available to read on my website in English language. When the project is exhibited, both parts are present: the images hang on the wall with the texts printed on tracing paper next to them. The curator Olga Matveeva helped me find this form for the exhibition.

Daria Sinaiskaia | Grandma With A Guitar | 2022

Daria Sinaiskaia | Grandma With A Guitar | 2022

Although this is a very intimate series, it resonates universally. What kind of reactions from viewers have moved you the most?

I feel very grateful when people reach out to me on social networks or in person during an exhibition to tell me which part of my project resonated with them. It is very interesting to hear what it is, because for each person, it’s something different. Sometimes people simply say, ‘thank you for what you did; it is so simple and touching at the same time’. But sometimes it is more precise.

One man who saw the project at the exhibition at the Photoplay school in Moscow, read all the stories printed next to the images. He was particularly touched by the story of my grandfather—by the fact that even though my grandmother separated from him because of his problems with alcohol, and they spent many years living apart, she took him back in his elderly years when he was no longer able to take care of himself.

Another viewer was moved by the story of my Aunt Vera. He said: ‘Her story is evidence that she never recovered from the Second World War; some people did not.’

I know for sure it is not easy to find the strength and courage to reach out to someone to share your thoughts or words of gratitude. This makes the effort even more significant. Without this feedback, it would be difficult to understand if what I do resonates with other people’s minds and hearts. I am very grateful for those who do it.

Daria Sinaiskaia | Grandma’s Mother | 2022

Daria Sinaiskaia | Grandma’s Mother | 2022

How do you hope “After Her” might inspire others to look differently at their own family histories?

I hope some people will rediscover objects they keep in their homes that belonged to their loved ones—that they will see the strange beauty and traces of history in them. I also hope that some people will find more significance in their family history and feel a wish to preserve it, whether through photographs, written stories, drawings, or video. For those who want to keep the memory of their family alive, even just for their children, I hope they can find their own way and approach.

I also dream about expanding this into a wider project where people could send me images of the objects they keep in memory of their beloved ones, accompanied by their stories. I have already started gathering some from my friends and plan to launch a website to collect these stories. My wish is to somehow make this project international, to gather stories about people not only from my country, but from around the world. I hope to find the way to do it in upcoming years.

All people have their family history. Many of us have objects that, for us, are a concentration of memory, love, and grief. This is something that still connects us as human beings in our often separated world. If my work can help to at least some people see their own family history as part of shared human experience—to see how much we all have in common, no matter where we live or what language we speak— I would be very happy for that.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.