Barbara Drobot

Where do you live: Batumi, Georgia (born in Kyiv, Ukraine)

Your education: B.A. in Architecture and Urban Planning

Describe your art in three words: corporeal · resilient · contemplative

Your discipline: Painting and drawing

How did your background in architecture and urban planning shape your artistic vision and the way you construct space on the canvas?

My experience in architectural and descriptive geometry still affects the way I approach painting. The balance, precision, and restraint I initially applied to city planning now echo on the canvas. The geometric shapes I employ are not accidental; they resemble architectural drawings, measured and carefully crafted. I often feel that my paintings carry the same sense of order and structure as a restrained balance of lines and subdued calmness that holds the composition together.

Why did you turn to the theme of corporeality and the ‘fragile threshold of human states’ in your work?

I did turn to the theme of corporeality because it became the most authentic way of speaking about my own mindset and sharing it with others. We live in a world where it is too inappropriate sometimes to place ourselves at the center, where selflessness is praised and self-revelation muzzled. In that environment, sensations are neglected or suppressed. To me, body painting was a way of giving feelings life. Migration made it even more urgent.

When we are not home, we wish to take care of loved ones but in doing so we forget about ourselves. The body never forgets, however. It is the only temple we will ever have and it both feels the visible burdens of external pressures and the intangible burdens of internal thoughts. By using the body to represent the vulnerable edge of human states, I am constructing an image of resilience — the body as both site of suffering and vessel of survival.

Barbara Drobot | Nowhere Inside | 2025

Barbara Drobot | Nowhere Inside | 2025

How do silence and inner rhythm manifest in your paintings?

Silence in my paintings is about presence. My paintings contain no one but me, and this creates an open space in which both I and the viewer can at last meet each other only with ourselves. In that encounter, there is no external noise. Just the internal quiet beat of life.

To me, this is essential: in a world that’s perpetually full of demands, comparisons, and distractions, art is a pause, a moment of pause. The rhythm of the body, of breathing, of thought, governs the composition more than any external story. I want the canvas to be a mirror where one can begin each day from personal needs and desires.

That inner rhythm is subtle but unceasing, a kind of pulse that lives us even when we are not aware of it. In painting the silence, I am not subtracting meaning but offering a return to the most intimate rhythm of life: the dialogue between the self and the body.

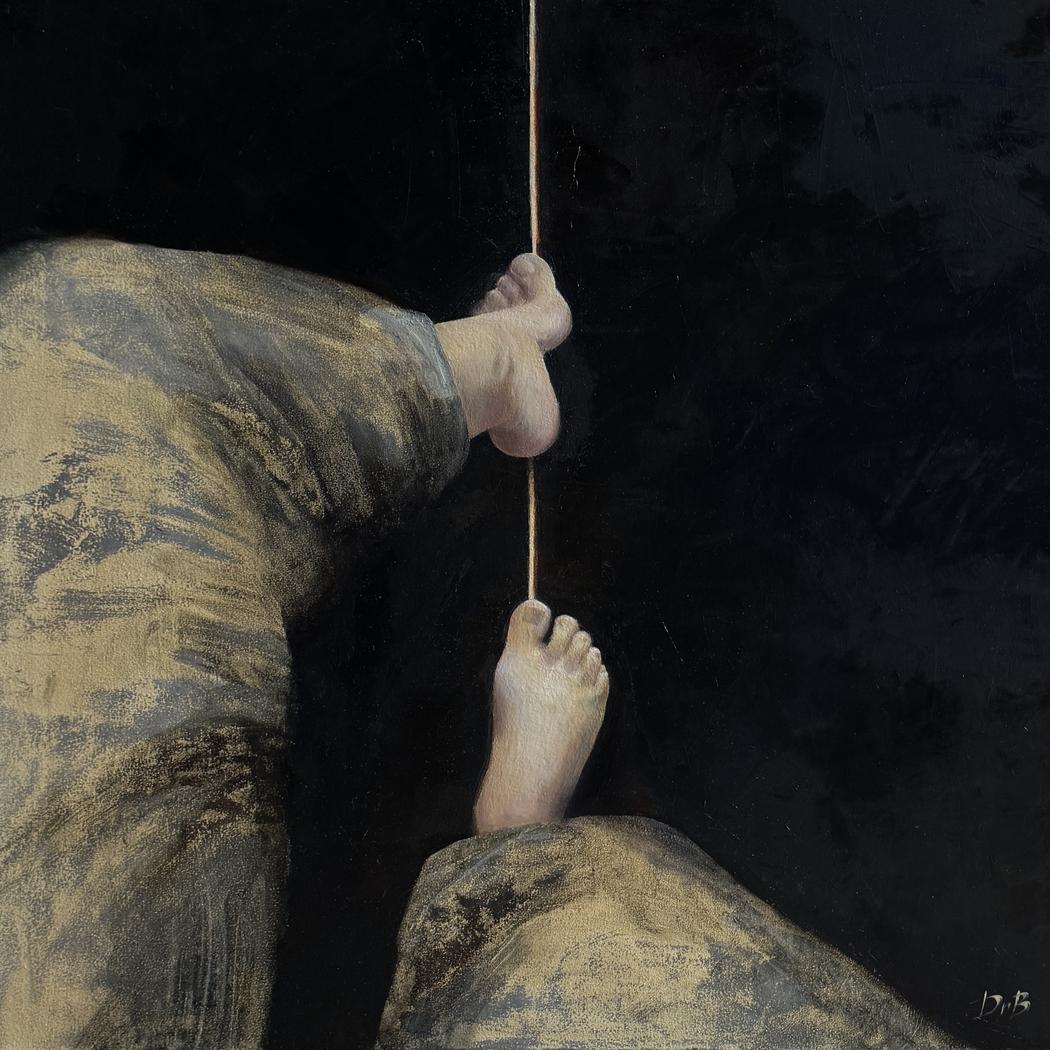

Why do you often choose to depict parts of the body — hands, feet, gestures — rather than complete portraits?

I rarely paint complete portraits because I believe that in public life we wear masks the whole time. Society forces us to present some face. Even when we tense, even when we want to scream, run, or escape, we smile. It is one of our means of living among people, every one of us with his own cause and burden. The face is the mask of politeness, but the body is not a liar.

Hands, feet, and gestures betray what words and sentences conceal. A clenched hand, a restless position, the way a foot pushes against the ground – all these betray discomfort or dammed emotion. The body discloses what we try to control: happiness, terror, vulnerability. With the focus on pieces, I am not diminishing the human presence, but I am increasing its authenticity. These limbs tell the truth of what goes on inside in ways that a face sometimes cannot. To me, gestures are more honest, more real. They whisper what the mask in the portrait conceals.

Barbara Drobot | The Threshold | 2025

Barbara Drobot | The Threshold | 2025

Your surfaces show textures, erasures, and frictions. Could you talk about your technique and how it supports the idea of suspended emotion?

My oil technique is strongly watercolor-influenced. I started in watercolor, discovering the transparent flow of it through my architectural training, and that art affects my technique in oil. When I turned to oil, I wanted to work with transparency, layering, and lightness—almost as if emotions themselves could be veiled. The surfaces I create are delicate layers that resemble shadows or veils. They conceal and reveal at the same time, like emotions suspended between being spoken and being silenced.

This layering, for me, is a metaphor for internal life: shadows wiped marks and the transparent surface reflect how we mask and conceal from our feelings. Below every layer, there is always something showing, like a memory trace of feeling that refuses to disappear.

These textures and erasures embody suspended emotion — present yet unexpressed, hidden yet not obliterated. I invite the viewer to sense that ephemeral tension: the balance between what is revealed and what remains concealed, the fragile transparency through which we greet one another yet so often fail to truly see.

How do teaching and working with students affect your own practice and the way you think about the human body and emotions?

Teaching also taught me, initially, that every process is time-consuming. Mine included. Observing students makes one realize that art is never meant to create a picture; it is about dealing with a theme, a method of questioning and discovery. I am grateful to be able to introduce a new philosophy of art to students. All of them arrive eager to do nothing more than create a ‘beautiful picture,’ but they find out before long that art is a way of speaking wordless to convey emotion, idea, and philosophy. It is a form of communication to others without words. In teaching, too, I learned to be more attuned to the body as a mode of unspoken emotion.

Students might smile when things go awry, but their hands, their posture, or even their voice might give away frustration or vulnerability. Pedagogical training has shown me how to see these subtle hints, to respect them, and to answer with empathy. This tuning goes back into my own practice: I see the human body not as shape, but as an emotional instrument, humming with truths that cannot be expressed at all times.

Barbara Drobot | Where Strength Ends | 2025

Barbara Drobot | Where Strength Ends | 2025

What role does time play in your work—both in the slow process of painting and in the stillness you invite the viewer to experience?

Personally, time is the most precious resource in the creation of a painting. There is a tendency in our culture to want to do things quickly, to have something to show that others will approve of. But if we consider art as research – essentially a creative-scientific inquiry – then we need to accept that research takes time. It’s about trying an idea in different ways, seeing what happens, and then keeping that process open to dialogue with ourselves and the world. In painting, time teaches patience and failure and demonstrates that there are no finite answers – no solely right or wrong results.

There are only facts, tracks, and interpretations of a particular concept. This is what I also present to the viewer: though I begin from my personal concept, every person who is faced with my work can recognize something personal – a sentiment, a fear, a joy. They can ‘test’ my concept through their own experience. In this way, time is not only what builds the painting, but also what occurs in the viewer’s experience, who is forced to slow down and undergo a process of discovery about himself.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.