MAO Yu Lynn Yuan

Your education: University of Hong Kong, MSocSc in Sustainability Leadership and Governance; University of Toronto, B.A. in Arts Management

Describe your art in three words: Thought-Provoking, Innovative, and Bold

Your discipline: Creating for a positive purpose

Website | Instagram

Your work bridges Eastern and Western cultural influences. How do you navigate and merge these two perspectives in your creative process?

MAO Yu Lynn Yuan: Eastern and Western cultures seem to be naturally integrated into my works that view the world from the perspective of a China-born, Canada-raised female film director. Mermaid in the Garden of Escapism is a film of particular significance to me. It marks my debut as a filmmaker, born during a period when I was grappling with countless life choices and the chaos of surroundings—its inspiration is drawn from an 18th-century English poem about mermaids. Its narrative weaves through the initial portrayal of the Mermaid by Gloria Gao, the final version of the Merman played by Huang Baoguo in reshoots, and the symbolic performance of Fung Kun who acted as the Butcher slaying two fishes without showing the face. A white tablecloth, an oversized white shirt, lemons that fate hurls at each of us…Regardless of gender, we seem trap in the cages forged by society’s imposed frameworks. The film’s ending ascends on the wordless melody of Deeper Than the Ocean—much like the Yin and Yang of Eastern philosophy, the two fish stand as a symbol of balance between feminine and masculine forces, neither complete without the other, for a world cannot exist with only one. After all, “Strength has no gender.” That unspoken finale might be love for some, struggles against fate for others, or perhaps an awakening of self for many. This film, conceived in 2019, premiered at CIFF in Canada on May 25, 2024. Spanning five years from filming, editing, and script refinement to production and promotion, it mirrors my own journey—like a silkworm shedding its cocoon, breaking free from a predetermined life path, and ultimately emerging transformed, having achieved self breakthrough and renewal.

In Mermaid in the Garden of Escapism, surrealist imagery plays a central role. What draws you to surrealism as a visual language?

MAO Yu Lynn Yuan: Dreams are the wellspring of my inspiration. Since childhood, I have been fond of sleep, and I often experience dreams that are surrealistic and visually ethereal—some even turning out to be precognitive, which unfolds in reality later on. In my works, I have used the transition between metaphorical scenes: the shift between dreams and reality, between slumber and awakening. Such symbolic elements—dreams, liminal spaces, and those seemingly random yet distinctive people and things that emerge in life—are in fact indicators guiding us to the answers within ourselves.

I maintain the daily habit of reading and writing, so over the years, I have amassed a vast library of information and knowledge. My reading spans a wide spectrum: from business, finance, and politics to culture, art, and fashion, and even extends to obscurely niche domains. Whenever I dream of or encounter something unusual, I research its connotations and symbolic meanings across different cultures, and write down my findings. In time, a rich, massive “database” has taken root in my mind. Take one dream as an example: I dreamed of a spider crawling toward me from the old courtyard of my late grandfather’s house. It grew bigger and bigger, swelling to a gigantic size, as if poised to attack me—in the dream, I seized the giant spider with one hand, just like one would grasp a large crab, and snapped off several of its legs with a crisp crack. Later, when I delved into the cultural symbolism of spiders and explored dream interpretation, I came to realize that part of my inner fear likely stems from patriarchal society—particularly the norms and constraints imposed on women by traditional families in East Asian societies. Yet my actions in the dream also seemed to symbolize that, deep down, I possess the courage and capacity to break free from such bonds, which are also shackles. Interestingly, I later used an AI tool to render this dream into a Tarot card: an elegant young woman calmly and gently capturing a giant spider with her bare hands. The image is quite amusing—the spider, flustered at being caught, even looks a bit cute. On the whole, it bears a resemblance to the “Ace of Pentacles” in Tarot, signifying the reconstruction of material foundations and other cornerstones of everyday life. Elements like the spider, when incorporated into audio-visual storytelling, can evoke emotions such as danger, unease, and fear. Films and other works of art, in essence, are the abstract transmission of emotional perception through a tapestry of such elements. The use of surreal imagery can craft an imaginative ambiance that transcends the boundaries of space and time. And the value of a creator lies in fostering emotional resonance that bridges cultures, spaces, and time.

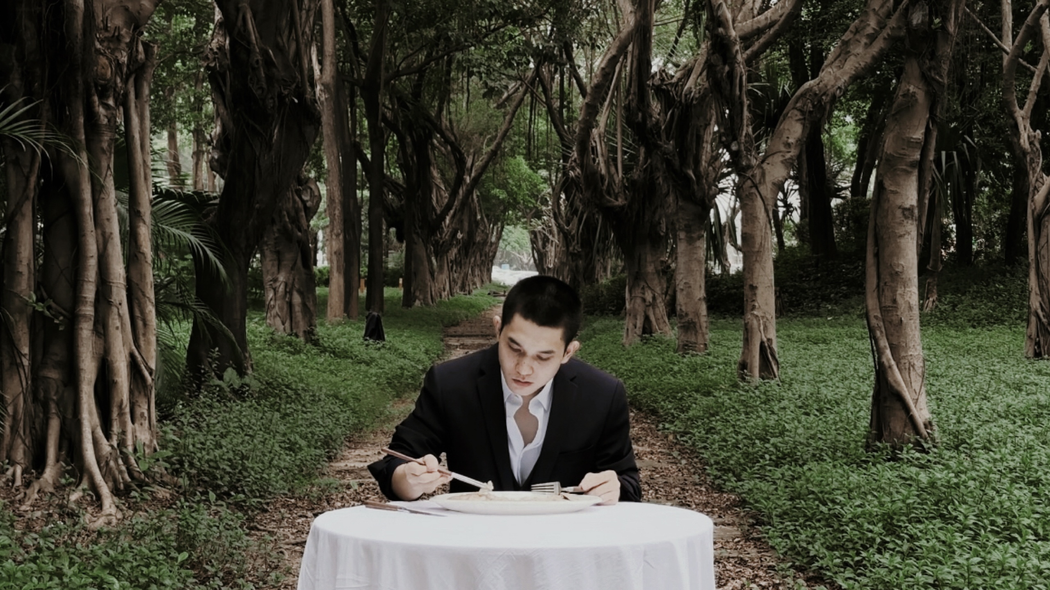

MAO Yu Lynn Yuan | Mermaid In The Garden Of Escapism | 2024

MAO Yu Lynn Yuan | Mermaid In The Garden Of Escapism | 2024

The mermaid is a recurring figure in mythology. What made you choose this symbol to explore themes of gender and agency?

MAO Yu Lynn Yuan: Andersen’s The Little Mermaid is one of my favorite fairy tales. The Mermaid is a character that has been repeatedly reinterpreted as women’s social status evolves—she is a hopeless romantic who sacrifices herself to save the prince, and also the sea’s daughter and princess, one who yearns for freedom and turns into foam to soar toward the sky. Meanwhile, she is an independent individual who must break free from the bondage of “the sea as a metaphor for patriarchy”—a force that serves both as a powerful refuge and a personal constraint—to claim a sky that truly belongs to her.

In my film Mermaid in the Garden of Escapism, I selected six female AIs from diverse age groups and cultural backgrounds to do the voiceover, and synthesized their voices to recite the same 18th-century English poem about mermaids. This poem, in essence, tells a universal female fate: though she is beautiful, noble, and pure, she ultimately remains trapped in a gendered social framework that objectifies women, with “being a good wife and mother” as its final chapter. The difference between the subject and the object lies in this: a subject’s life is a story of “who I am,” while an object’s life is a story of “whose I am.” When we examine such established social frameworks through the lens of gender, we will find that men are expected to achieve success throughout their lives, whereas women are expected to “marry well.” Most people spend their lives in a hasty blur, trapped in these gendered frameworks and invisible social norms—they neither attain the so-called “success” they truly desire, nor stay ignorant of what lies beneath the surface of “marrying well.”In reality, people are taught how to achieve success or how to “marrying well,” yet few are guided on how to “be oneself”. Among East Asian cinematic works, Big Fish & Begonia (2016) by Chinese animation directors Liang Xuan and Zhang Chun, The Tale of the Princess Kaguya (2013) by Japanese animation master Isao Takahata, and Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000) by Chinese Taiwanese director Ang Lee all explore the conflict between the awakening of individuality and collectivism. When an individual enters a family, a clan, or any specific collective, they usually bear the inescapable shared responsibility and karmic fate of “prosperity for all when one prospers, and ruin for all when one falls”—a fact that is often overlooked in the grand narrative of collectivism.

Returning to the unique symbol of the Mermaid, she represents the awakening of female individuals. For “being yourself” is, to some extent, a privilege. During my tenure as a mentor at a non-profit organization for female entrepreneurs, I was introduced to a tool for the equality movement—the Wheel of Power/Privilege. By deconstructing contradictions within social hierarchies, it provides a theoretical foundation for understanding equality. Twelve color spectrums list a series of indicators that can be quantified by hierarchy, such as identity, age, gender, wealth, and education. The closer one is to the center, the more privileges they possess; conversely, the farther one is, the more marginalized they become in society. In essence, it resembles a form of order that constitutes the collective world. In this chaotic era ushered in by the pandemic, people are mired in various confrontations—bickering about gender conflicts, talking about class solidification, and worrying about the uncertainties of what is to come tomorrow and next year. Yet, the inherent strength derived from each person’s unique self knows no categories: it transcends gender, has no hierarchy, and carries no distinction between nobility and inferiority. It requires no proof to others, nor does it depend on how many positions one holds on the Wheel of Power/Privilege or how close one is to its center—it is something that enables people to unconditionally accept and love themselves in every moment, especially the present. We can call this “love”—starting with self-love, extending to love for others, and finally reaching out to the broader world. This is also the core theme I proposed in a TEDx talk earlier this year: “Embrace Your Uniqueness.” It is also a privilege in the ideological realm—a privilege that many people never truly notice or realize they can freely possess at any time: the power of being yourself.

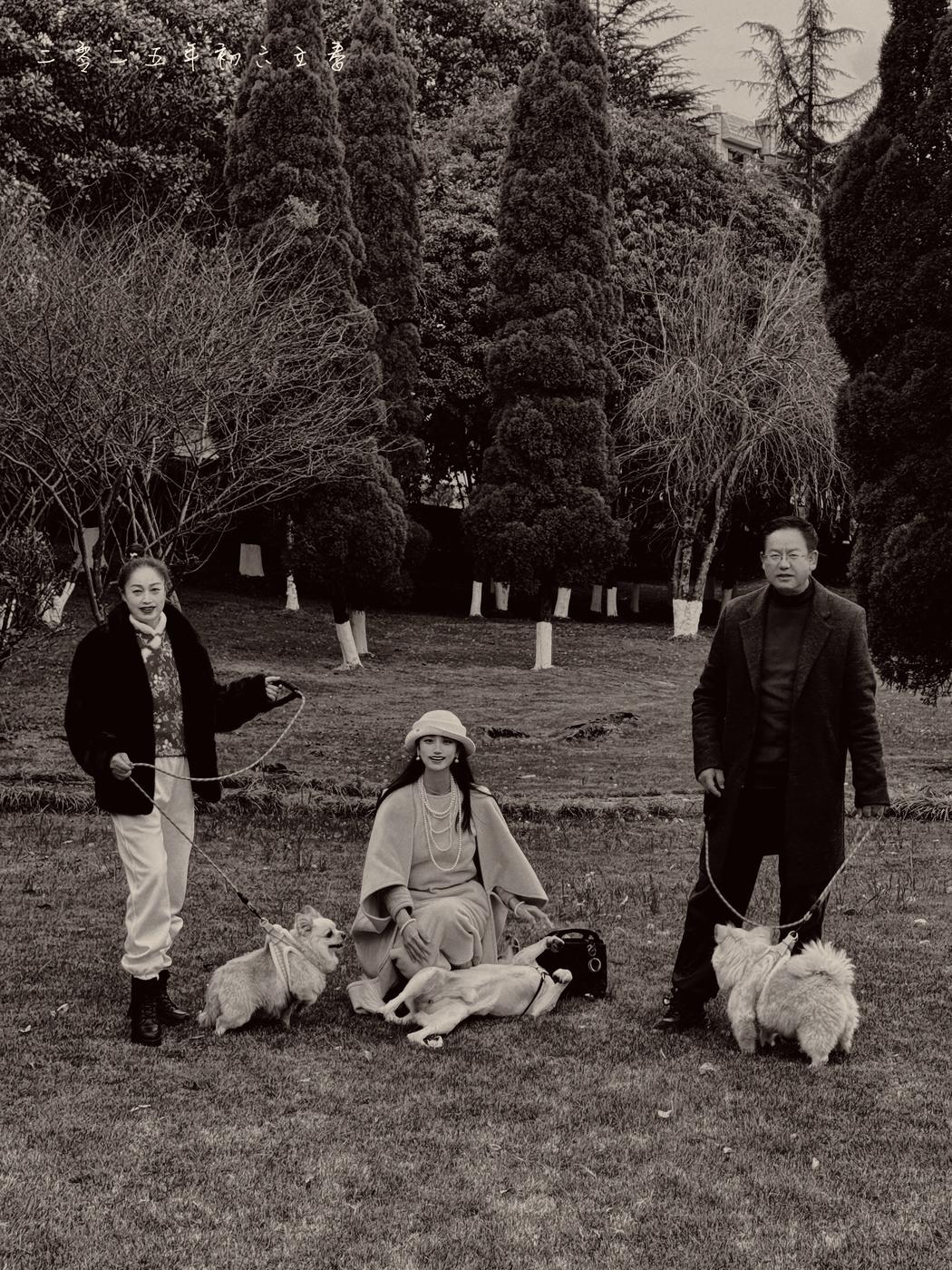

MAO Yu Lynn Yuan | Mermaid In The Garden Of Escapism | 2024

MAO Yu Lynn Yuan | Mermaid In The Garden Of Escapism | 2024

The film uses vivid color contrasts and layered literary metaphors. How do you approach balancing visual beauty with thematic depth?

MAO Yu Lynn Yuan: A work from a filmmaker’s perspective—an artist’s expression—is essentially a manifestation of how the storyteller observes and engages in dialogue with the world. I don’t think they’re contradictory or conflicting in a way. It’s like—when the right conditions are met, women actually don’t need to balance family and career. The depth of a theme depends primarily on the early stage of creation—essentially, the story itself—and the core of that lies in what kind of story you want to tell. Visual appeal, on the other hand, is a matter for the filming and production process, which is something built on the foundation of the story. To frame it vividly, we can liken the art of film to a tree: the story is the roots, and the visuals are the branches. At its core, the art of cinema is a form of conveying ideas. So the essence of what it seeks to express far outweighs how aesthetically pleasing its presentation is.

As for visual allure, I’ve nurtured a passion for painting since my childhood. I garnered awards and had the artworks published when I was a kid. When I first started as a young entrepreneur in the creative domain, I chose the fashion industry as my path of passion. In the capacity of a creative director, I crafted a multitude of fashion art editorials and films for the magazine in circulation at that time. When it comes to aesthetics, it’s like a foundation built up over time—so I never really polished it on purpose. Instead, there are times when I need to check myself the other way around: will the composition and setting end up looking too much like a fashion editorial? This is something to which I must pay extra attention in the future, particularly when filming and producing content that embodies a more life-like essence. When filming surrealistically, people don’t notice this issue.

MAO Yu Lynn Yuan | Mermaid In The Garden Of Escapism | 2024

MAO Yu Lynn Yuan | Mermaid In The Garden Of Escapism | 2024

You deliberately used AI-generated voices in the film. How do you see AI as both a tool and a metaphor in your storytelling?

MAO Yu Lynn Yuan: AI voiceover in the film reflects a lack of voices. In this chaotic, complex world, we encounter artificial intelligence also searching for order. Fear, surprise, anxiety, trust…When these emotions intermingle, who could have imagined that right now, and for years to come, those supposedly cold super Artificial Intelligence systems may crave nothing more than the fleeting emotions that make us human? The role AI plays in human society is much like that of power: a double-edged sword with intersecting impacts. Just as power itself is neither right nor wrong—what is wrong lies only in the people who misuse it to harm others—the same logic holds true if we replace “power” with “AI.”

AI, as a tool can be customized, yet it may also create information cocoons that deepen cognitive divides. Take the six AI female robots I intentionally selected—each representing different ages and cultures: their speaking speed, tone, emotions, and content can all be tailored. This mirrors human experience, especially for women, who have long lived within frameworks that objectify them. It seems they spend their entire lives surrounded by pre-customized voices. It’s not that opportunities don’t exist for them; rather, more often than not, the “voices” around them act like an information cocoon, telling them: This is the only path your life can take. And this applies to men as well. AI is also much like a mirror reflecting our human society. If algorithmic models are the “brain structure” of AI, then data is the textbook that shapes this brain. If those textbooks hold biases, AI inherits them, creating closed loops that makes problems unseen and away from a solution. Yet many now call AI their “best friend,” using it to project emotions and resist nihilism. In this sense, AI doesn’t just reflect collectivism—it gives individuals the option to step outside of it.

MAO Yu Lynn Yuan | Mermaid In The Garden Of Escapism | 2024

MAO Yu Lynn Yuan | Mermaid In The Garden Of Escapism | 2024

How has your dual education in Toronto and Hong Kong shaped your views on individuality versus collectivism in art?

MAO Yu Lynn Yuan: To a certain extent, collectivism is associated with unity, yet it also harbors inevitable dark sides of human nature such as rivalry and envy. Individuality is often linked to solitude, which is accompanied by inner freedom and self-exploration. An individual who does not engage in energy exchange with the outside world can hardly develop spontaneous, diverse views on the world—this is much like the balance one must strike between “this-worldly path” (engaging with society with a sense of responsibility) and “other-worldly path” (focusing on oneself with as few human connections as possible). In the film Mermaid in the Garden of Escapism, the Eastern philosophical concepts of “Yin” and “Yang” are embodied through two fish that repeatedly appear as metaphors. This explains why the male and female leads are portrayed as the male and female versions of a mermaid: they not only symbolize men and women, but also represent the masculine and feminine forces in the world. This can be seen as a philosophical wisdom of seeking balance amid numerous contradictory dualities.

I was born in mainland China, moved to Canada as a teenager, and later relocated to Hong Kong, China in the wake of the pandemic. I see myself as part of a generation raised amid the fusion of Chinese and Western cultures. My childhood was steeped in fairy tales: back when China had just joined the WTO and globalization was gathering momentum, every time my dad returned from a work trip, he would bring me a multicultural gift—Barbie dolls, Hans Christian Andersen’s fairy tale collections, DVDs of Japan’s Anmitsu Hime and America’s Betty Boop from that era…I still keep all these to this day. As a teen, I attended an international school in Shenzhen—a “window city” of China’s reform and opening-up—where I received an education that wove together Chinese and international values. Starting around my teens, as I entered adulthood, I chose to embark on an entrepreneurial journey during my college years while observing society—and all these life chapters unfolded in Canada, my second homeland. My undergraduate studies in Arts Management at the University of Toronto afforded me the freedom to create freely and nurtured a critical mindset. Having loved reading and writing since childhood, I can express myself fluently in Chinese characters and shift between Chinese and English translation with literary grace—a unique bond I share with Eastern culture, particularly Chinese culture. Many subtle nuances of artistic conception in Chinese are irreplaceable in English; conversely, the distinctive beauty of numerous English words defies precise conveyance in Chinese. This is an inherent trait of every culture, much like how an individual’s uniqueness is nearly impossible to replicate. Yet it was only in recent years—when the pandemic allowed me to live continuously in my homeland, China, for three years as an adult for the first time—that I truly began to delve into in-depth research and integrate Eastern culture into my cognitive framework.

In my first year back, I planned to take a family portrait, but my grandfather—who had chatted and laughed with me just a week prior—suddenly fell ill and passed away in the hospital. It was the first time I witnessed the death of a loved one: I held his hand and watched his ECG flatline amid the beeping sounds. The following year, my grandmother also passed away in her twilight years. In the third year, coinciding with the production of the mermaid film, my cat—who had been my companion for over a decade—died of cancer in Toronto. During these years, some friends endured hardships due to their parents. In the typical East Asian social structure, where families are bound by the principle of “prosperity for all, adversity for all,” an individual’s fate often rises and falls in tandem with their family’s. Endowed with a strong sense of empathy since childhood, I observed these events of friends—unrelated to me yet emotionally resonant—from the sidelines. When it came to life’s profound questions of life and death, separation and reunion, and individualism versus collectivism, I felt as if I was “taking intense lessons” through others’ life stories, with one after another, with more lessons still to come. For a long time, I was deeply affected by the negative impacts of these tales of others’ fates, which eventually gave birth to this debut mermaid film. Later, I learned to let go of the savior complex and respect the fate of others. It wasn’t until I sat down to draft my own TEDx speech script that it suddenly dawned on me: Oh, those are other people’s life stories. THIS IS the story of my own life journey.

I fly frequently between China and Canada. One moment, I might be immersed in discussing filming plans with friends in Toronto; the next, I’m switching to a conference call with friends in Beijing to talk about quadruped robotic dogs; soon after, I’m coordinating with friends in Hong Kong on which international forum to attend. My master’s studies in Sustainability Leadership and Governance at the University of Hong Kong, coupled with Hong Kong’s role as a bridge for cultural exchange between China and the world, have provided me with a perfect platform to leverage my strengths as someone raised with both Eastern and Western cultures. Cultural shocks are inevitable, but I have never viewed Eastern and Western cultures as opposites. On the contrary, when they merge deeply and strike a balance—much like the Yin-Yang harmony emphasized in Eastern philosophy—this unity becomes a form of art, a strand of life wisdom, and a reflection of the high-level harmony attainable in our human society.

To be honest, the past few years of navigating Sino-Western cultural shocks have felt like stepping aboard a light-speed spaceship in a dream. The world around me seems to peel away layer by layer; as the spaceship passes through different places, the people I encounter blur and sharpen in my memory in equal measure. I have long stood outside one comfort zone bubble after another, overcoming one fear after another. At first, it felt like traversing one tunnel after another; later, it was like driving down one dark highway after another. But in the end, I realized that all my fears were nothing more than “fears I’ve crafted in my own mind”—much like how I always rely on GPS, treating it as a habit and a source of inner security. One day, my phone died, GPS ceased to work, and there was no one ahead to guide me forward. In that moment, I felt insecure and briefly panicked. But the key insight emerged: I have always known how to find my way, with or without GPS—or rather, I no longer need it. After all, a change-maker doesn’t need GPS; they themselves are the direction. When Shakespeare wrote, he likely didn’t dwell on the “thousand Hamlets in a thousand people’s eyes.” If he had overthought such things, we wouldn’t have the masterpieces we cherish today. This mirrors how people need to choose the “this-worldly path” to engage with the collective for energy exchange, yet ultimately must return to their inner selves—the “other-worldly path”for refining life wisdom in solitude to become a better version of themselves.

MAO Yu Lynn Yuan | Mermaid In The Garden Of Escapism | 2024

MAO Yu Lynn Yuan | Mermaid In The Garden Of Escapism | 2024

What conversations do you hope audiences will have after watching Mermaid in the Garden of Escapism?

MAO Yu Lynn Yuan: One lies in the power of “being oneself” amid individual awakening. Awakening does not mean abandoning the ambition to become a better self, sinking down to nihilism, or withdrawing from the world to be free and caring about nothing. Instead, it means gaining clarity on who you truly want to be, where you truly want to go, and what kind of life path you truly want to forge from the depths of your heart—and earnestly tending to the driving force behind your life: your mind. When reflecting on every pivotal breakthrough in life, nearly all of them stem from the strength brought by “being oneself”. You did not take the path everyone else chose, nor did you worry about whether others liked it or not. You did not even fret over whether the value of investment matches the gain. Instead, you followed your inner voice and did what you believed in and desired without needing a reason. And surprisingly, it “succeeded.” The strength comes not only from “being oneself” but also from the inner stability fostered by the sense of selfhood gradually built over time—you no longer search for the meaning of the present in hesitation, the past, or the future. For the world inherently has no meaning, yet you come to understand that your existence is the meaning itself. Society may seem to impose numerous rules and frameworks to restrict us, but in truth, the greatest limitation we face has always been the ones we set on ourselves.

Another lies in the boundaries within collectivism. This year’s Zhongyuan Festival—a time to honor ancestors—I did not follow the traditional rituals of burning incense, paper offerings, or lighting lamps. Instead, amid my reverence and remembrance for my deceased ancestors and loved ones, I fed a flock of geese and a few squirrels, and continued reading chapters from a novel about three generations of Jewish women in America. Even in privileged middle-class American families, there exists a first-generation mother who died in a mental asylum after suffering domestic abuse at the hands of her husband, a successful and independent second-generation woman who treated “marrying well” merely as an “accessory,” and a third-generation daughter who lived in the shadow of her mother—a glamorous, successful woman who was rarely home. There are no perfect people in this world, let alone perfect families. “Not quite forever, almost forever”—this line, from the book, was spoken by the third-generation daughter to the second-generation woman (her mother) when talking about this female bond of kinship. I find it beautifully poignant; it also vividly depicts the invisible thread of female connection that tethers them to each other amid the fleetingness of life.

When it comes to the father’s role in the collective unit of “family”—a role that often symbolizes strength, serving as both a protective shield and a restrictive cage—and the other form of connection that is male intergenerational inheritance, I once wrote a poetic passage from the perspective of “a son/daughter writing about his/her father”:

Seeing a mountain as a mountain;

Seeing a mountain not as a mountain;

Seeing a mountain still as a mountain.

After all these years,

The mountain remains a mountain,

And I remain myself.

The mountain has been the mountain;

I have been myself.

I am myself.

When we discuss the value of individuality, collectivism, and the relationships and boundaries between people, the inescapable conclusion is ultimately humanity’s inherent loneliness, and the essence of life: resisting entropy. People strive to live to counteract the chaos of the world. Isn’t it true that AI and AI-driven robots designed to “resemble humans” are trying so hard to gain the same ability as humans to resist such chaos? When more and more of us humans learn to love ourselves, respect our own lives and the lives of others with kindness, the inequalities in those seemingly opposing orders—marked by hierarchy based on gender, wealth, and power—may gradually diminish, just like the process of resisting entropy. And these are also the ideas behind the stories I aim to tell in my second film, which is currently a work-in-progress. The answers we so eagerly seek in life have always been within ourselves. May you find yours as well.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.