Luna Xue

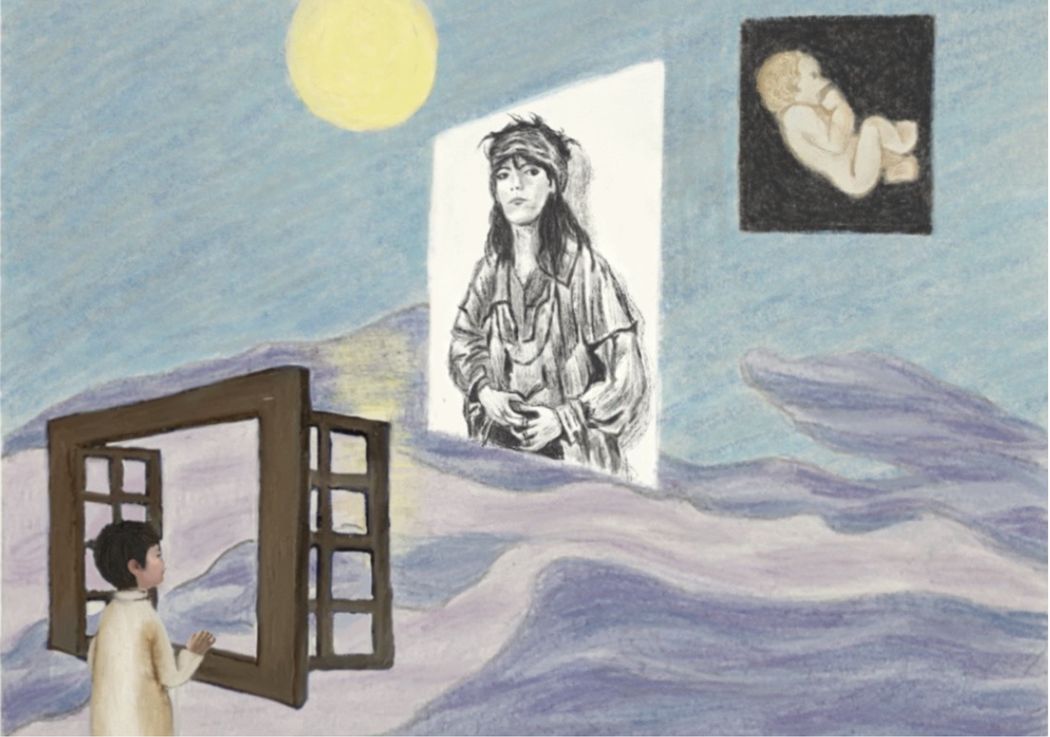

Luna Xue | Kids Talking

Luna Xue | Kids Talking

Could you tell us about your early artistic experiences and how your grandfather influenced your creative path?

I grew up in Ningbo and was raised by my grandfather. He was a traditional artist specializing in Chinese calligraphy and ink painting, and he was also my earliest artistic guide. We often went sketching in the mountains or visited exhibitions together. He taught me to understand emotions through visual perception and encouraged me to freely express my inner experiences. This immersive artistic education in my early years deeply shaped my understanding of “seeing” and “expressing.” My artistic practice has always been about storytelling, and that storytelling was first rooted in family memory.

Luna Xue | Kids Talking

Luna Xue | Kids Talking

How did your studies at the Edinburgh College of Art shape your artistic style and direction?

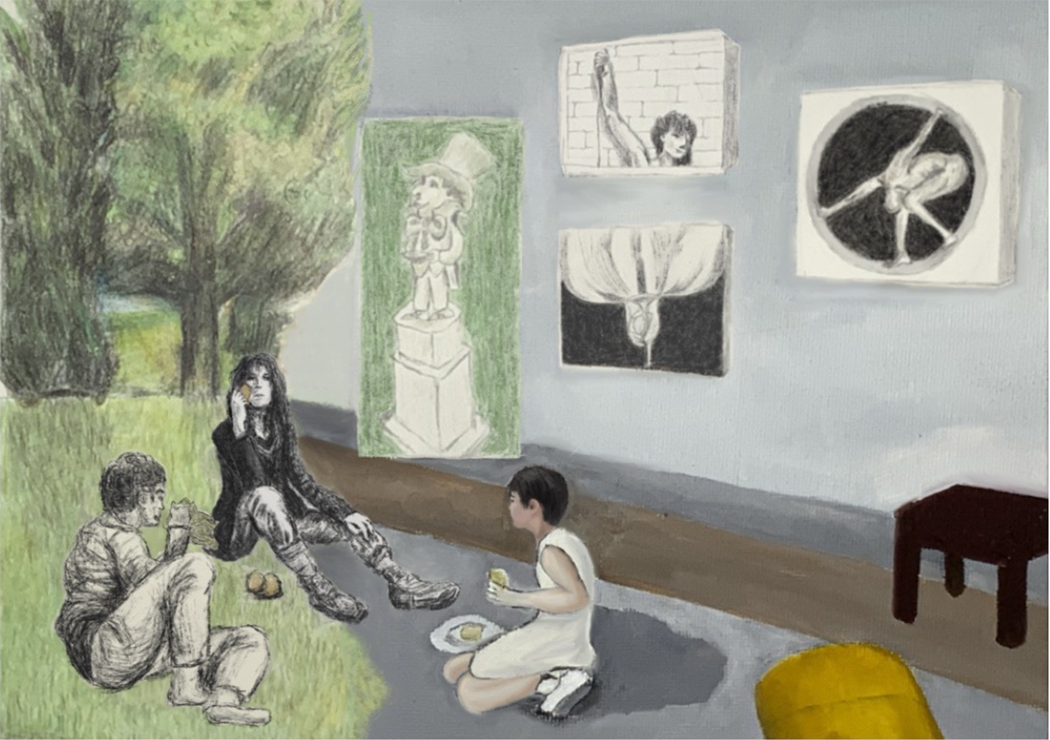

During my MA studies in Illustration at Edinburgh College of Art, I began to understand image-making from a more conceptual and research-driven perspective. Gradually, I moved beyond representational imagery and turned to multi-disciplinary forms such as installation, sound, and text, attempting to build a “narrative field” through multiple dimensions. At the same time, this experience also led me to re-examine my own cultural identity and gendered experience, placing personal narratives within a global context. Though the forms of my practice are diverse now, narrative remains its core.

In your practice, how do you balance traditional techniques with contemporary themes?

I don’t see traditional techniques and contemporary themes as oppositional. In my paintings and installations, one often finds calligraphic brushstrokes, symbolic structures, or the use of negative space—these all stem from my perception of Chinese visual traditions. Meanwhile, the themes I explore face the contemporary moment head-on: gender-based violence, intergenerational trauma, or societal silence. I try to weave bodily experience and cultural memory together, forming a visual text that is both emotional and critical.

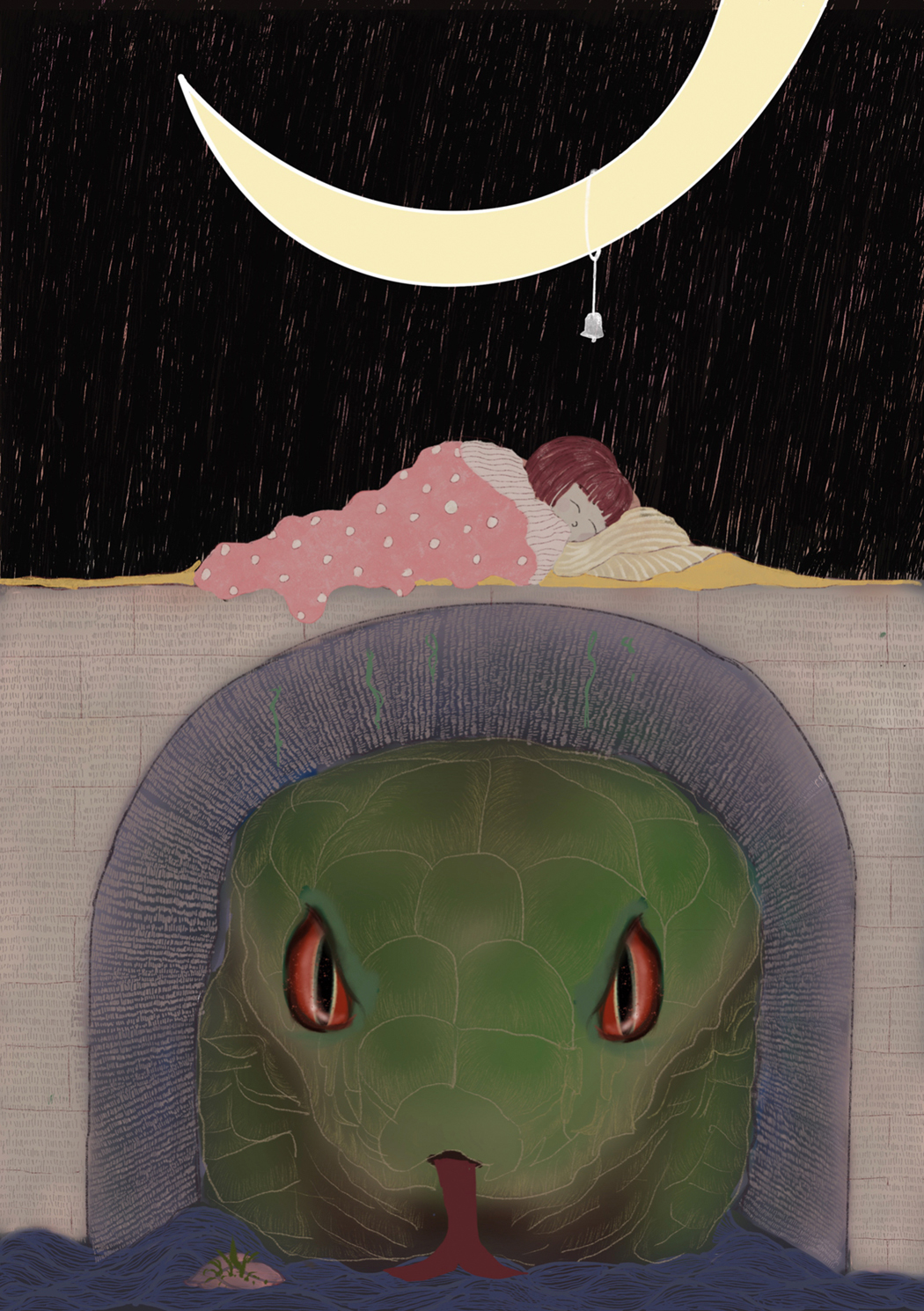

Luna Xue | What Was Taken

Luna Xue | What Was Taken

Many of your works explore intergenerational trauma and female identity. How do you approach such deep and complex personal topics?

For me, individual trauma is never isolated—it reflects structural silencing and cultural suppression. For instance, in Kids Talking, children’s voices are played on loop in a disembodied way, detached from physical presence. This method of “de-corporealized” speaking is meant to expose how society continues to suppress language around gender, violence, and consent. This is not merely a “women’s issue”—it’s about how language is constructed, denied, and distorted. I try to make silence itself into something that can be sensed.

Luna Xue | Kids Talking

Luna Xue | Kids Talking

What challenges do you face when translating personal memory into visual narrative?

The biggest challenge in transforming memory into artwork is finding a balance between honest expression and avoiding emotional excess. I don’t want to objectify or commodify trauma. That’s why I often use indirect visual language—fractured narrative structures, blurred imagery, delayed and disrupted sound. These strategies prevent the work from being a “reproduction of the past” and instead present a structural rendering of silence, absence, and deferral. I’m more interested in how “stories that cannot be told” might visually surface.

Luna Xue | What Was Taken

Luna Xue | What Was Taken

Have you noticed different interpretations of your work from audiences with different cultural backgrounds?

Definitely. In exhibitions in Europe, audiences often interpret my work through psychological or psychoanalytic frameworks, whereas in East Asia, many viewers more naturally associate it with family culture, gender roles, and mechanisms of silence. I welcome these diverse interpretations—they’re a vital part of cross-cultural dialogue. My work does not attempt to convey a singular position; rather, it opens a space that can be entered through multiple lived experiences.

01.jpg) Luna Xue | Resonance

Luna Xue | Resonance

Which materials or media do you currently feel most connected to?

I currently work primarily with imagery, sound, and hand-crafted materials. Painting remains a foundation, but I increasingly use sound installations, collages of old objects, and even books and embroidery. For example, Triptych of Silence was created with minimal, desaturated tones to express an emotional spectrum in the aftermath of sexual violence—numbness, rupture, and echo. What I seek in these media is not “effect,” but the residue of experience. Materials carry meaning; they are vessels of narrative.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.