Christoph Bossart-Lee

Where do you live: Zurich, Switzerland.

Your education: Mostly self-taught, inspired by my mother’s practice and my parents’ obsession with art, as well as my wife’s gentle nudging. I took classes at Paris’ École des Beaux-Arts and Zurich’s F+F School of Art and Design.

Your discipline: Painting and sculpture.

You describe skin as both a metaphor and a material inspiration. Can you share what initially drew you to explore this theme so deeply?

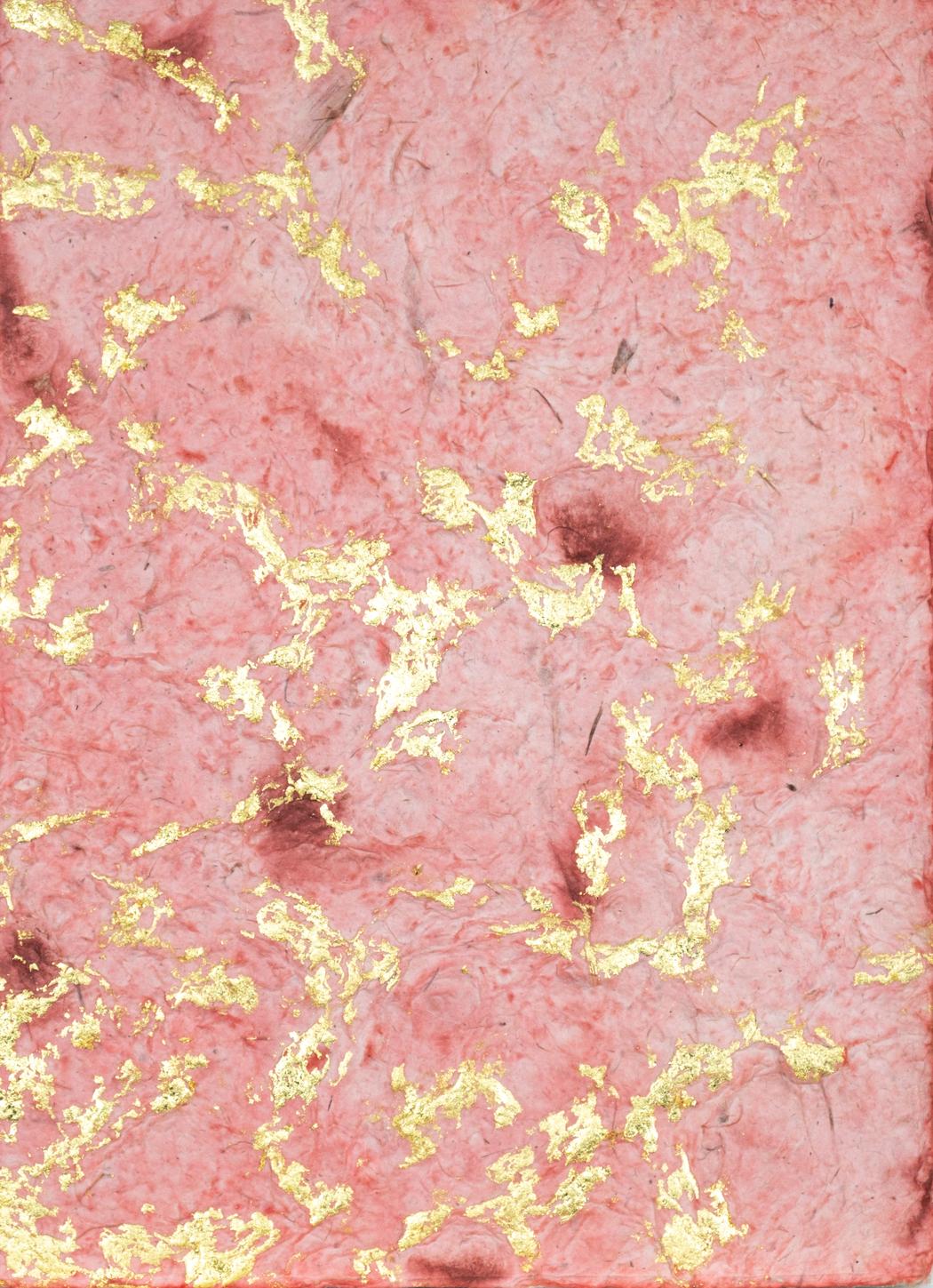

Skin is often marked with small cracks and wounds, which, when closely examined, reveal an immense source of inspiration. There’s a visual richness of the colors, textures and structures. Skin can be opaque or translucent. Its color is made up of countless tiny dots—almost like pixels—in an endless range of shades and hues.

My skin takes up quite a bit of time and headspace. Living with atopic dermatitis, it’s been a source of discomfort and, in the past, embarrassment. The idea now is to turn this experience into something beautiful. So, there’s an introspective dimension to my interest in the theme. At the same time, skin is universal. Everyone has one, and everyone has a relationship with it.

But skin is not just an aesthetic subject; it also functions as an archive of physical and psychological life. Skin cells hold memories, reflect a person’s lifestyle and condition, and serve as a communication tool while also shielding us, as best they can, from the outside world.

That said, I sometimes hesitate to attach too much symbolism to my work, as I hope to create something that others can find beautiful without context.

Many of your works incorporate close-up textures and imperfections. What role does macro photography play in your creative process?

Macro photographs of skin and other materials are a source of inspiration. These images are like maps inviting exploration, the forms of skin imperfections like letters of an alphabet waiting to be deciphered. They’re usually a starting point for a painting or sculpture and help guide the shift from the realism of my subject to the abstraction of my work.

Christoph Bossart-Lee | Layers | 2025

Christoph Bossart-Lee | Layers | 2025

There’s a fascinating tension in your work between vulnerability (cracks, wounds) and beauty (gold leaf, delicate surfaces). How do you approach this contrast?

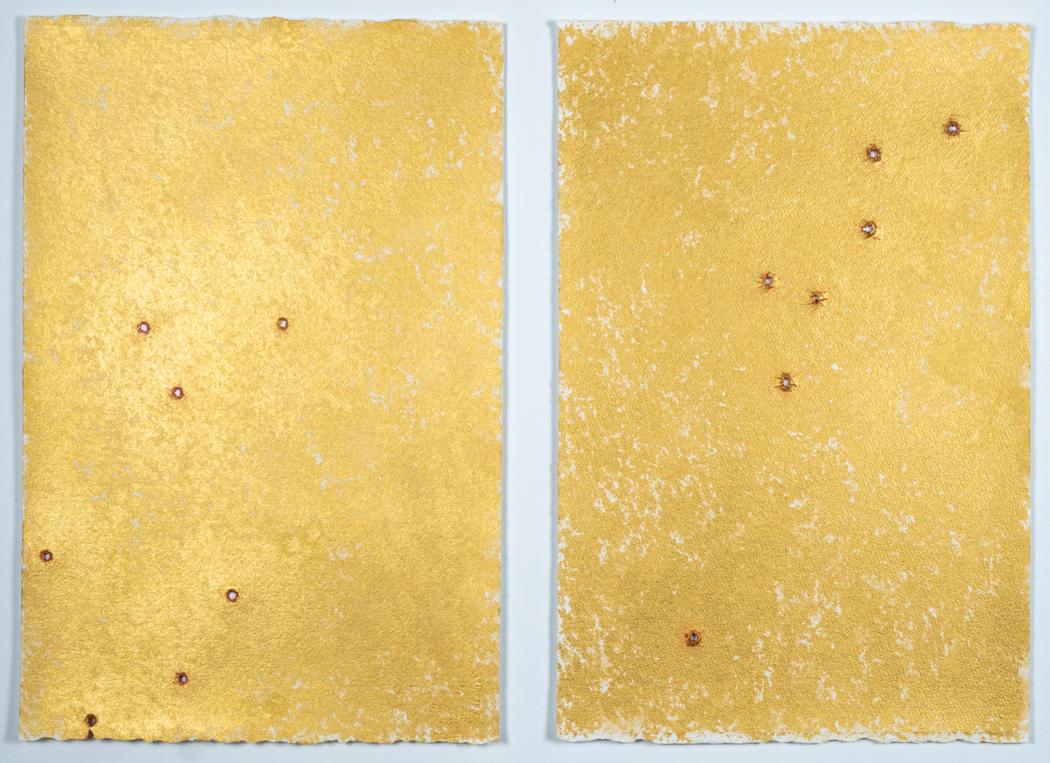

I’m looking to find beauty in imperfection and fragility. I don’t think everything is beautiful, but I believe that through some sort of transformation, ugly things can become beautiful. “Art is the wound turned into light,” said Georges Braque.

One way to reach transformation is through close observation. If you zoom in far enough on anything, even the vilest object, it becomes something else – open to reinterpretation. Another way is abstraction. A photo of a nasty wound can be turned into something beautiful through simplification or decontextualization. A third is figurative reinterpretation (This wound looks like a goat!). And then there is choice and combination of materials: matching two things that don’t belong together, like delicate gold leaf and thick, cratered Hanji paper, creates tension and dialogue, and in the best of cases, beauty.

In Japanese Kintsugi, gold is used to highlight rather than hide repairs in broken ceramics. That practice transforms the object into something more beautiful and unique because of its history, not in spite of it. I quite like that perspective.

Could you tell us more about your time at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris and how it shaped your recent work?

I had a great teacher in the life painting classes I took. He helped me a lot with painting what I see and not looking for a representation of the object in front of me. It was often frustrating – there are many traps to fall into, and I did so frequently – but also very liberating.

The classes also challenged my attachment to precision, which I aimed for but regularly failed to achieve. They gave me confidence to give up on lines, focus more on blots of paint and be more gestural and expressive

My teacher advised me to look at a model’s pose as a letter of an unknown alphabet. That stuck with me, and it continues to inform my wound alphabet series.

Christoph Bossart-Lee | Kortison | 2025

Christoph Bossart-Lee | Kortison | 2025

Your artistic journey began through textile design. How has that background influenced your current practice?

My grandfather had a carpet business, and carpets were very present in my childhood. A carpet in a family home collects memories – stains, pressure marks from furniture, wear and tear. Maybe that connection planted the seed for exploring skin as a collection of memories.

Me working with textiles was inspired by these carpets. And it made me appreciate materials; the savoir-faire that goes into them, learning about the properties of different fabrics. To me, there is incredible beauty in a piece of blank fabric. It taught me the value of white space. This translates to paper. For my practice, the choice of support medium is as important as the paint. I enjoy looking at a blank sheet of paper that is the result of centuries of craftsmanship. It makes me want to do it justice and paint only what’s necessary.

Some of your pieces appear almost sculptural or tactile. What attracts you to working with surface and texture in such a physical way?

That has to do with the subject matter. Skin is three dimensional, topographic, so it was a natural evolution.

It’s a different kind of practice than painting: more craft-like and planned. It tests my patience, but I learn a lot through it – about materials, mediums, and bonding agents, whether it’s Hanji paper, rice glue, or aluminum molds.

And Hanji is more than a surface to paint on – it’s also used in conservation, repair, and architecture. It invites physical work.

Christoph Bossart-Lee | 2023

Christoph Bossart-Lee | 2023

How does your personal experience with atopic dermatitis affect your artistic vision and emotional engagement with the work?

My life with dermatitis has certainly taught me that things pass and happen in waves. It gets worse, it gets better, then worse again. This is comforting to know and helps me when I struggle creatively.

The process starts from a personal perspective, but I’m looking for universality through practice and abstraction. As I said earlier, it’s about getting some beauty out of the ugliness and discomfort, which probably also has to do with overcoming the emotional urgency I felt as a kid when, for example, showing up to boy scout camp with a bag full of creams, ointments and bandages.

I hope the confrontation with my experience – as trivial and insignificant as it may be in the grand scheme of things – keeps my work authentic and reflects the tension between fascination, obsession and frustration.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.