Vladimir Punin

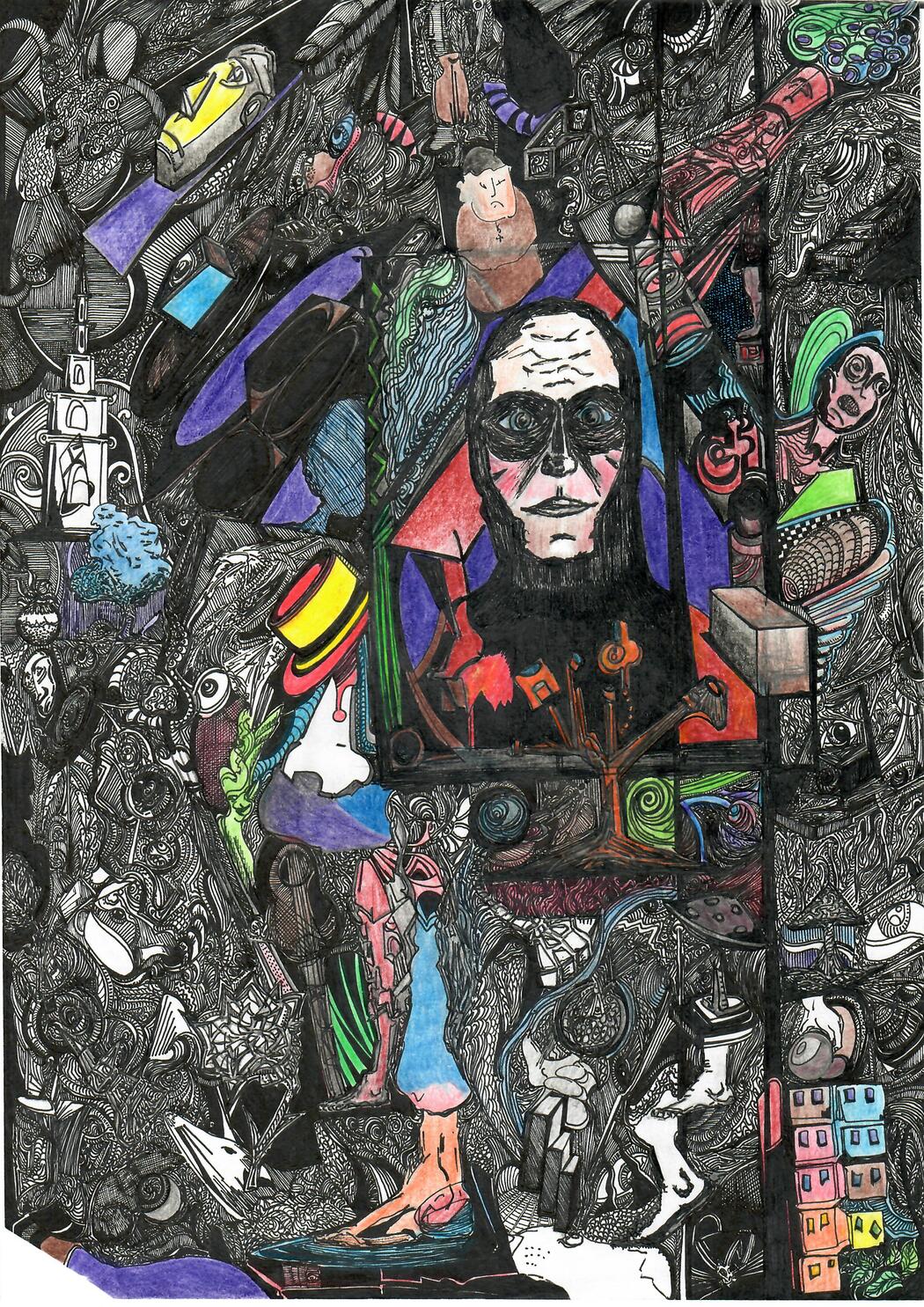

Vladimir Punin | When You Don’t Want to Look Back | 2023

Vladimir Punin | When You Don’t Want to Look Back | 2023

Your artwork often features intricate lines and abstract forms. Can you share the process behind creating these complex compositions? How do you decide on the placement of each element?

First, a certain image appears — it becomes the guiding star of the work. It is not a static picture, but a kind of action: a small visual fragment is born, with a beginning, climax, and resolution. Initially maturing only in thoughts and emotions, but becoming tangible and weighty, it begins to ask to be put on paper — and when the pressure becomes unbearable, I start the physical process. In other words, the piece is already complete before its actual execution.

Of course, my works are drawing and graphics, where the main elements are placed in their positions first, and then the composition is filled in across the primary fields. The seeming complexity arises from the peculiar merging of several images into one, where the linear sequence breaks in the most unexpected places, crumples, and fuses into a single, simultaneous representation. It’s like a series of photographs united by one idea for sequential viewing — but then passed through a shredder and laid out as a single image. This creates visual chaos.

However, it’s difficult to call my works chaotic, since all these lines and abstract forms appear not randomly, but through deep emotional, intuitive, and intellectual reflection. Yes, I do not strive for clear boundaries or an easily readable visual component — the viewer will independently perceive everything they need to. It’s a fundamental property of our brain to assign familiar and understandable images to everything it sees. The answer is often within ourselves.

The theme of death and the fleeting nature of life is quite prominent in your work. How does this concept influence your creative process, and what do you hope to convey to the viewer through these ideas?

They say that just before death, a person sees their whole life flash before their eyes. I remembered this phrase as a way to illustrate an idea — not to question the factual truth of it, but to express a concept. That is, an entire life, many years, rush by in a compressed, instantaneous moment.

If you abstract yourself and try to look at everything — literally everything in the world — all at once, you realize how immense the number of events happening right now truly is. So many, that if you try to think about them all at once, right here and now, you understand just how fleeting a human being is. It’s impossible to grasp the multitude of occurrences. And within each of us, there’s a vast world that exists only here and now.

For me, the topic of death, quite literally, is about life in the present moment. When the past no longer exists and the future has not yet arrived. One could say that in time, everything is dead — except for the present moment. There’s a kind of sorrow and an incomprehensible desire to preserve or hold onto so much within the fleeting instant of the now.

In everyday life, we don’t often encounter this feeling. And when we do, we usually brush it aside quickly, continuing to live by inertia, preoccupied with our affairs. But in extreme situations — and they are often connected with death: war, disasters, terminal illness — we are face to face with the fragile, easily torn, and swiftly ending reality of the world.

Vladimir Punin | Fading Surge of Expectation | 2023

Vladimir Punin | Fading Surge of Expectation | 2023

You mentioned that your background is not in art, yet your work is deeply artistic. How did your non-artistic education shape your approach to art?

Yes, my education is connected with people with disabilities. A person tries to rationalize life — to explain situations, seek causes, observe consequences — but more often, they are faced with confusing and random coincidences. People sometimes find themselves in circumstances where they can no longer live the way they used to. This happens when illness strikes, when someone is caught in war, is born with a disability, or ends up in an accident.

For example, you’re walking down the sidewalk, and suddenly a car crashes into you. You’re left injured, with a broken spine, learning to live again and trying to understand — why you? This happens often. Some parents spend their whole lives wondering why their family was the one to have a child with special needs. People who return from war often can’t make sense of why they survived — why they came back wounded, or why they came back without a scratch while their comrades are dead, or left without limbs, with shattered minds.

Life is a mix of patterns and a vast number of accidents, mysteries, and confusion. I think this is clearly reflected in my work.

In your piece “Fading Surge of Expectation” there is a sense of stillness despite the intensity of the work. How do you balance emotion and calmness within your art?

The act of creation is a deeply personal, almost intimate process, unrelated to the outside world. It’s like diving into a bottomless pool — or rather, into a solitary body of water covered in silt and algae. Down there, in the dark, without light or air, you freeze — alone with your feelings, emotions, and experiences. The only light is the light of your mind, and the only air is what remains inside you.

And when the sensation arises that you cannot go any deeper, you force yourself to return to the world — a world filled with color, light, people, emotions, and everyday hustle. I think this very moment — as you mentioned — is where the balance can be felt. If you go too far, you risk irreversible tragedy. But if you get scared and come back too quickly, the act of creation won’t happen at all.

![]()

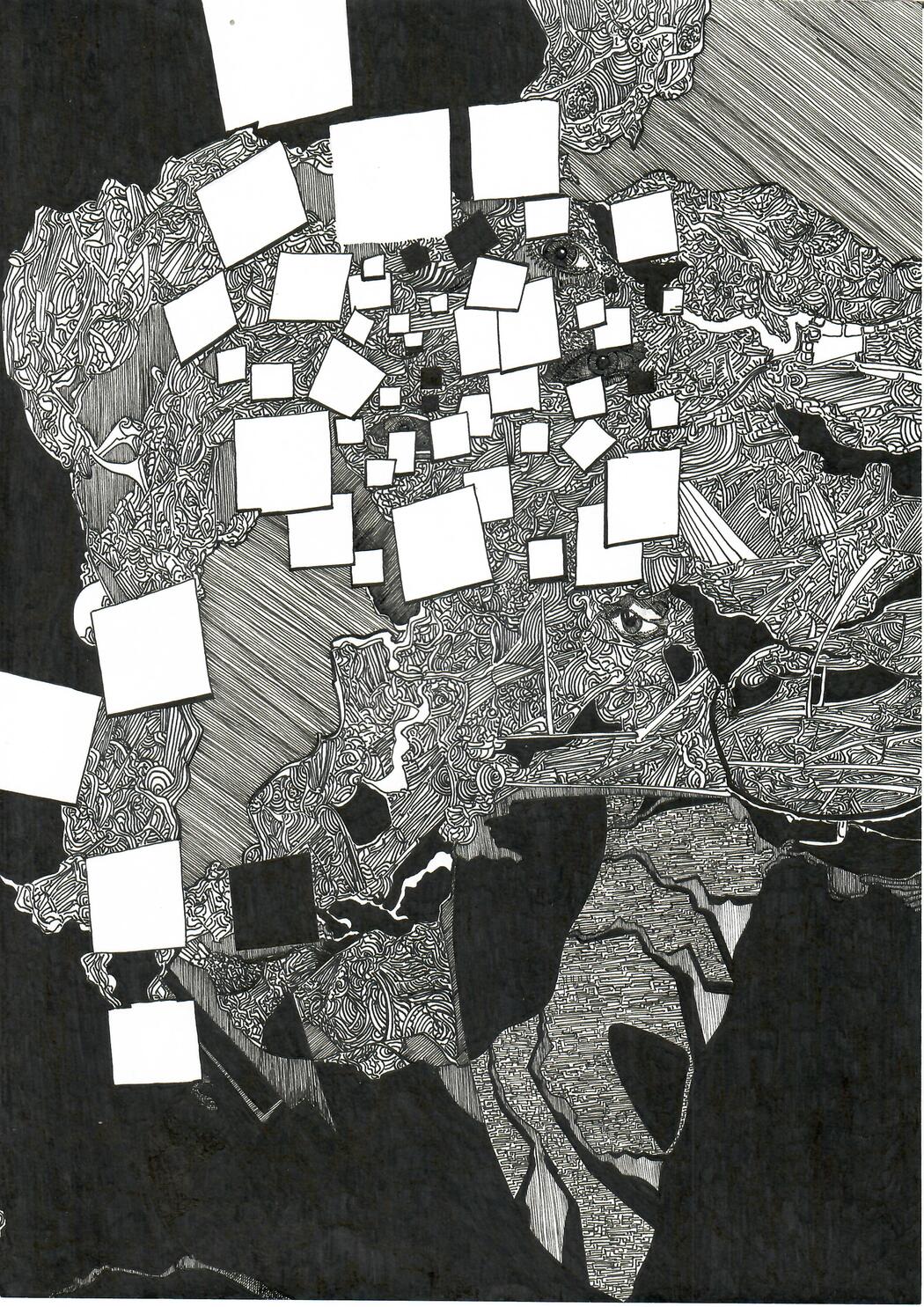

Vladimir Punin | Without Icons | 2024

Your art often features dark, intense contrasts. What role do light and dark play in your work, both literally and symbolically?

I’ve always been drawn to artists’ drafts — the reference point from which the artist begins, the sketches made with simple pencil or charcoal, when the future artwork is only just beginning to take shape and no clear artistic solution has yet been found. When the artist is still at a crossroads, contemplating the further development of the piece — that ambiguity is mesmerizing. It’s a kind of bifurcation point of fate, because at that moment the artist could abandon the sanguine, tear up the sketch, and destroy the future work altogether. How many such conceived but unresolved creations do we know of?

Sometimes, it’s in these moments that life itself is decided. I would say these drafts are independent works in their own right — both from an artistic point of view and in terms of worldview and philosophy. Light and shadow capture these states very precisely — black and white — while all other colors can be added by the power of one’s imagination.

How do you decide when a piece is finished? Is there a moment when you know it’s complete, or is it an ongoing process?

This is a completely intuitive part of the creative process — more precisely, its completion. If all the emotions and all the images that have been haunting me are poured onto the paper, and the work no longer evokes a creative response, then I consider it finished. Quite literally, my hand no longer reaches for the tools, the paper, or the easel.

Since my works generally lack a clearly defined central element — unlike, for example, portraits, where the background does not play a decisive role and the artist’s focus is on depicting the person — they may give the impression of being unfinished. And I’m sure that when looking at them, it’s easy to think that the painting was either abandoned or still in progress. But that’s not the case. These impressions are also part of the work itself.

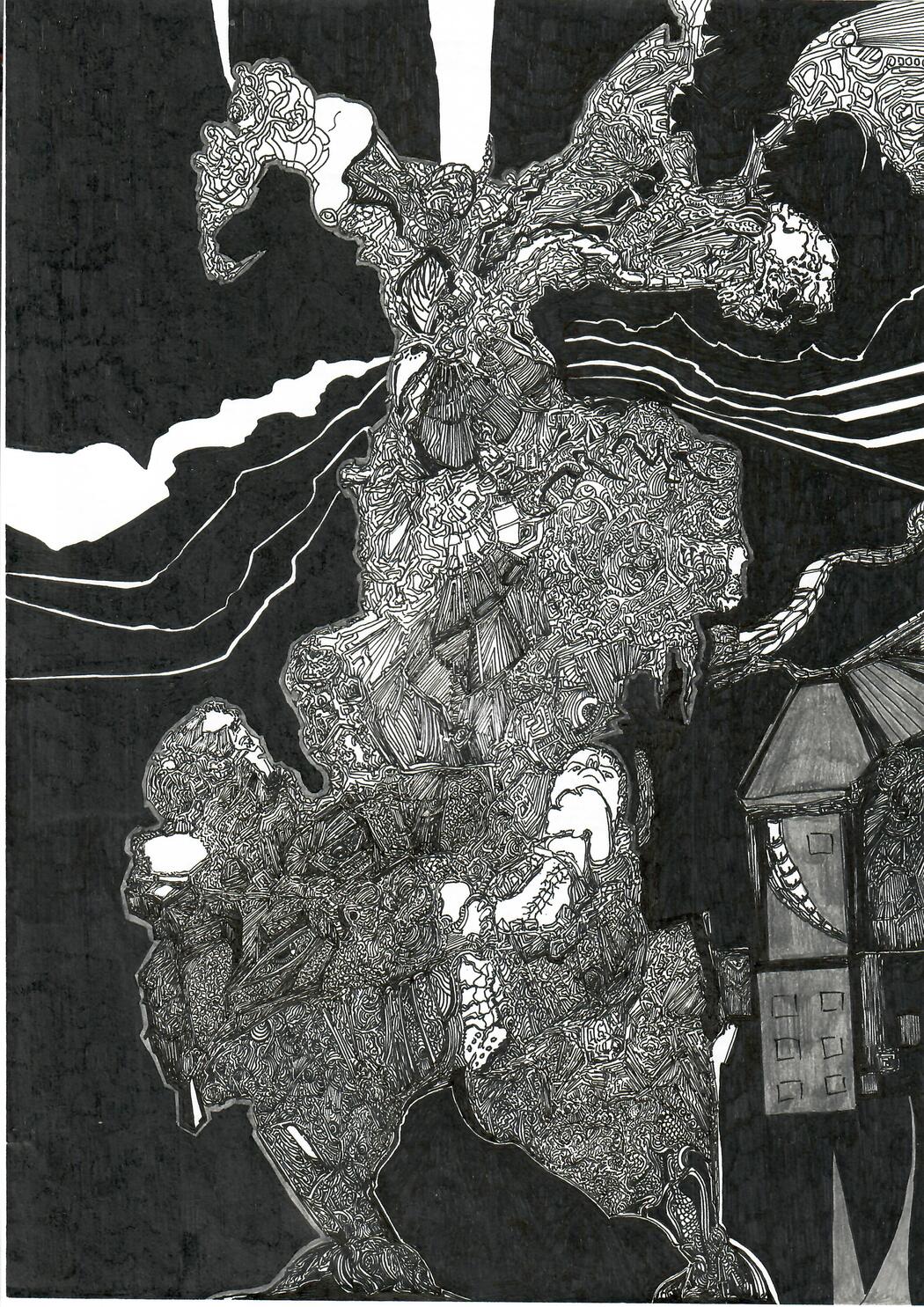

Vladimir Punin | The Reaper | 2023

Vladimir Punin | The Reaper | 2023

Many of your works feature a strong connection to mortality. What drives your exploration of death in your art, and how does it relate to the human condition?

Death equalizes everyone — sooner or later, it touches us all. Of course, this is a very old, well-known, and overused truth. And through understanding it, we realize that we have still not managed to cope with or overcome the awareness of death. We often prefer to fantasize, speculate, try to predict — but despite all our efforts, we haven’t come any closer to the horizon of knowledge.

Death, in one way or another, always remains a mystery — and mysteries are always alluring. It is like a code waiting for its decipherers. I would add that, aside from being a deeply tragic subject, death is also a very calm, quiet one — requiring solitude, seclusion, and focus. And, surprisingly, through the exploration and study of death, the full richness of life is revealed.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.