Claudia Missailidis

Your work often revolves around intimacy, silence, and desire. How do you translate these abstract emotions into visual form?

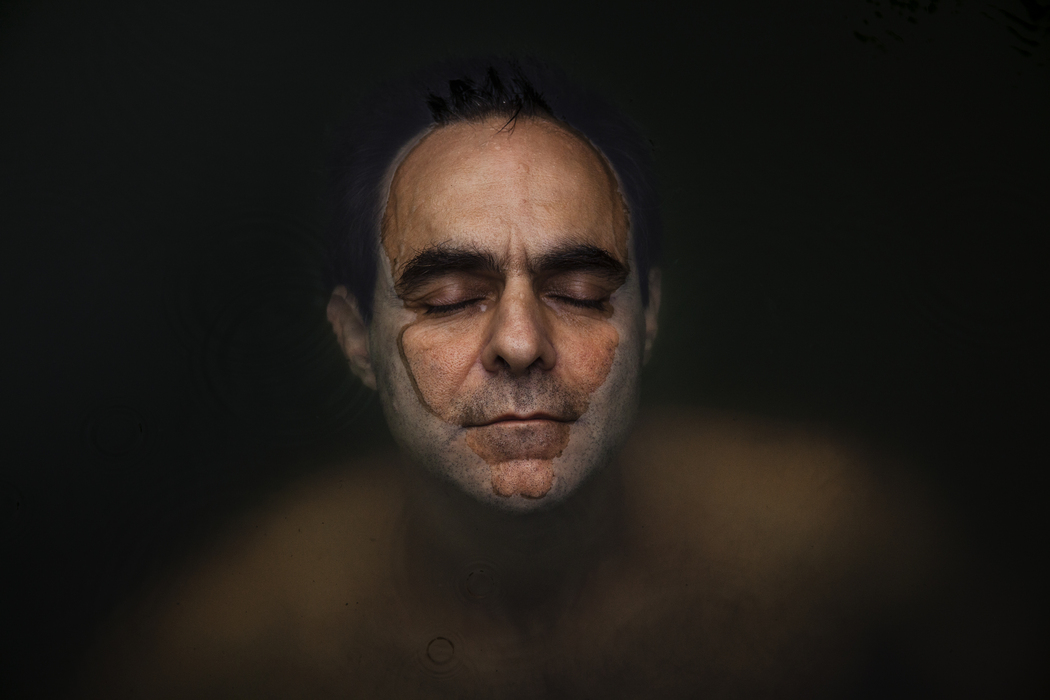

Intimacy manifests itself for me in the restrained gestures, in the light that slowly moves across the skin, in the space between the bodies that almost touch. Silence is not absence, but substance, it resides in the voids, in the pauses, in the shadows. Desire, on the other hand, appears as a subtle presence, almost a restlessness that lingers around the image without ever fully revealing itself. My process begins with listening, but not to sound. I listen to the environment, to the memory, to what has not yet been said. I try to let the image emerge from this initial silence, as if it were itself asking to come into being, to exist. In this approach, the body becomes a symbolic territory: not an object, but a place of passage, of memory, of invention.

You describe photography as a rupture and re-signification. Can you elaborate on how this concept manifests in your creative process?

Photography is a cut in time, a rupture that interrupts the flow of perception. It is there, in that interval, that the image can open itself to new interpretations. I like to work with the fragmentation of the body, with reflections and distortions that unsettle and destabilise the immediate reading. These visual resources are not aesthetic effects, they are ways of questioning what is expected to be seen, of reconfiguring what is understood as body, presence, beauty. This re-signification transforms photography from document into visual poetry: something that does not illustrate, but provokes. It is within this space that my work is anchored, where the visible becomes permeable to the symbolic.

Claudia Missailidis | Estudo luh

Claudia Missailidis | Estudo luh

There is a strong poetic and dreamlike quality in your imagery. What influences your visual language—literature, cinema, personal memory?

My language is born in the friction between memory and image. Literature and cinema are strong presences, of course, but it is the affective experience that guides the gaze. Writers like Pablo Neruda and Zygmunt Bauman help me think of the body as a place of desire and absence, while artists such as Francesca Woodman, Sally Mann, and Jan Saudek influence me by the way they treat the body with symbolic intensity. But my work is born, above all, from the skin and the memory. Many of the bodies I photograph belong to people close to me, in spaces that carry shared stories. These are places where something has already happened: friendship, love, loss, waiting. Photography, for me, is a way of stitching all of that together, what was, what remains, and what still pulses.

Many of your photos explore themes of the body, vulnerability, and eroticism. How do you navigate the boundary between exposure and protection in your work?

This is a fundamental tension in my work. The body that appears in my images is not there to be consumed, but to be listened to. I work with a nudity that is, above all, emotional, an assumed fragility, a presence that does not perform. There is always a pact of trust. I often photograph people who are intimate to me, in shared environments, and this requires a constant ethical listening. I do not photograph to expose the other, but to welcome what they have to offer me. Eroticism, in this sense, is not separate from care, it is precisely its closeness to vulnerability that interests me. Photography, for me, is a place of negotiation between what is revealed and what is protected. And to protect, sometimes, is also a way of loving what one photographs.

Can you talk about the symbolism in your use of water and reflection in your photography?

Water is a metaphor for fluidity of desire, of identity, of perception. It reflects, but it also distorts. It reveals, but never in a literal form. I like to work with water as this unstable element that resists and prevents certainties and invites multiple interpretations. There exists something ancestral and mysterious about water it is said to have memory, to carry traces of what it has touched. This idea interests me because it brings water closer to memory and affection, as if it were a sensitive archive of experience. Beyond that, water also carries within itself the transformation: it changes states, escapes fixed forms, adapts, evaporates, freezes, overflows. This quality of constant transition, of being between one state and another dialogues and resonates directly with the themes I explore: the instability of identity, the multiplicity of perception, the body in transit. The reflection, in turn, is like a second skin an image that returns altered, that opens fissures in reality. These elements help me construct visual and symbolic layers that disorganise the perception and suggest sensory pathways. More than representing something, they invite a crossing through the image like a dive into instability, memory, and transformation.

How do your studies in biology and physics inform or intersect with your visual art practice?

Very much so. Physics taught me to listen to light, not just as a technique, but as living matter, capable of constructing atmospheres and affections. Biology brought me closer to the body as an organism, fragile and mutable, with its cycles, its limits, its pulse. This background gives me tools to observe with both precision and sensitivity. I try to reconcile the rigor of science with the openness of art what can be measured and what escapes. Photography, at this point, becomes a hybrid field: between the concrete and the symbolic, between what is visible and what can only be sensed.

Claudia Missailidis | Finite Time

Claudia Missailidis | Finite Time

What role does gender and sensuality play in your exploration of the human condition?

Gender, for me, is flow, not a fixed structure. I work with bodies that move, that don’t fit into rigid categories. This fluidity is essential to thinking of the body as a space for multiple narratives. Sensuality in my work is neither fetish nor seduction: it is language. A way of touching the other through the gaze, through presence, through silence. The image becomes a place where bodies recognize one another without the need to perform. In this way, gender and sensuality are tools for accessing the complexity of the human experience, for revealing what is often made invisible or pushed to the margins. The body, in this context, is a space for listening, for confrontation, for reinvention.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.