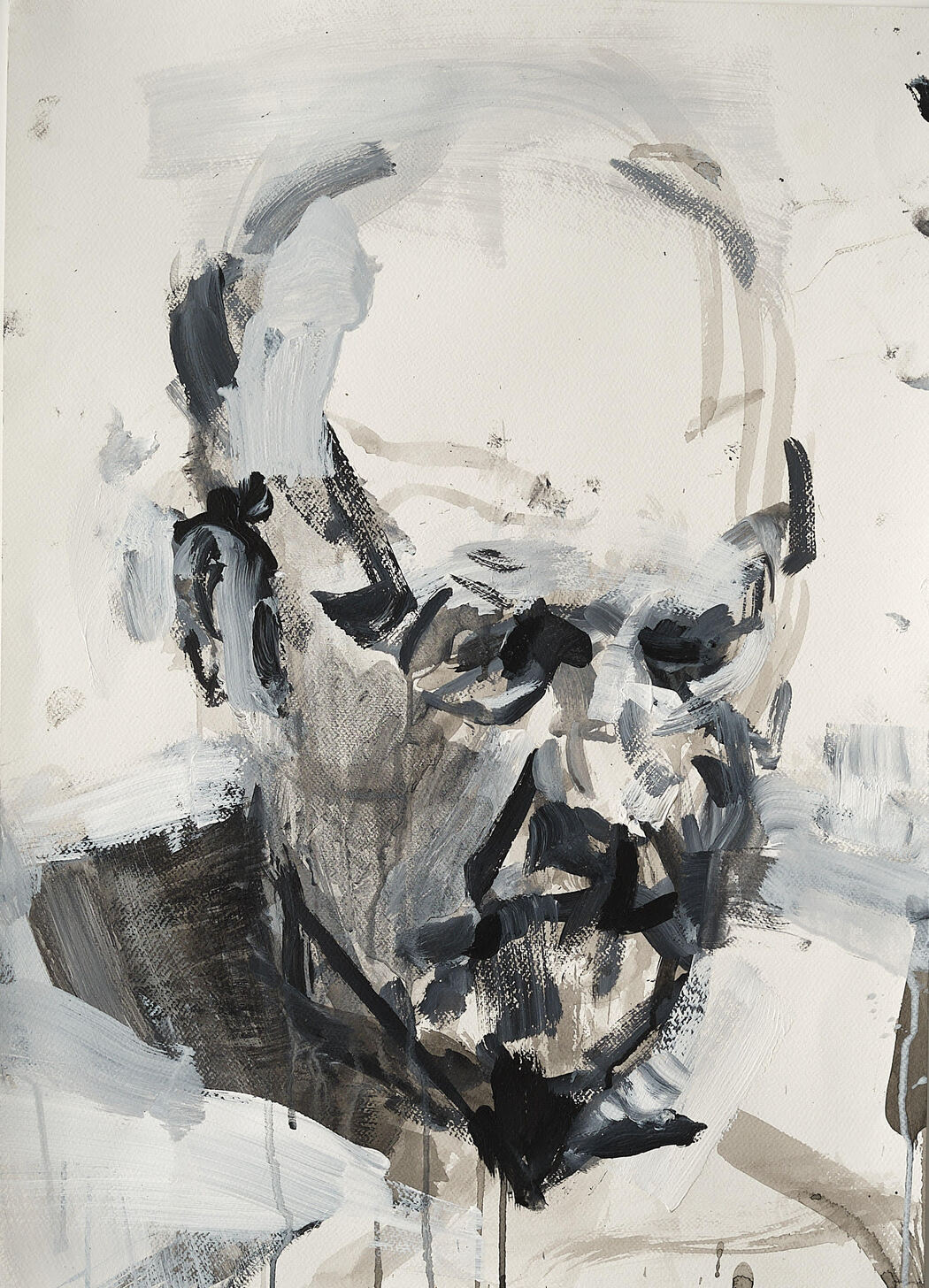

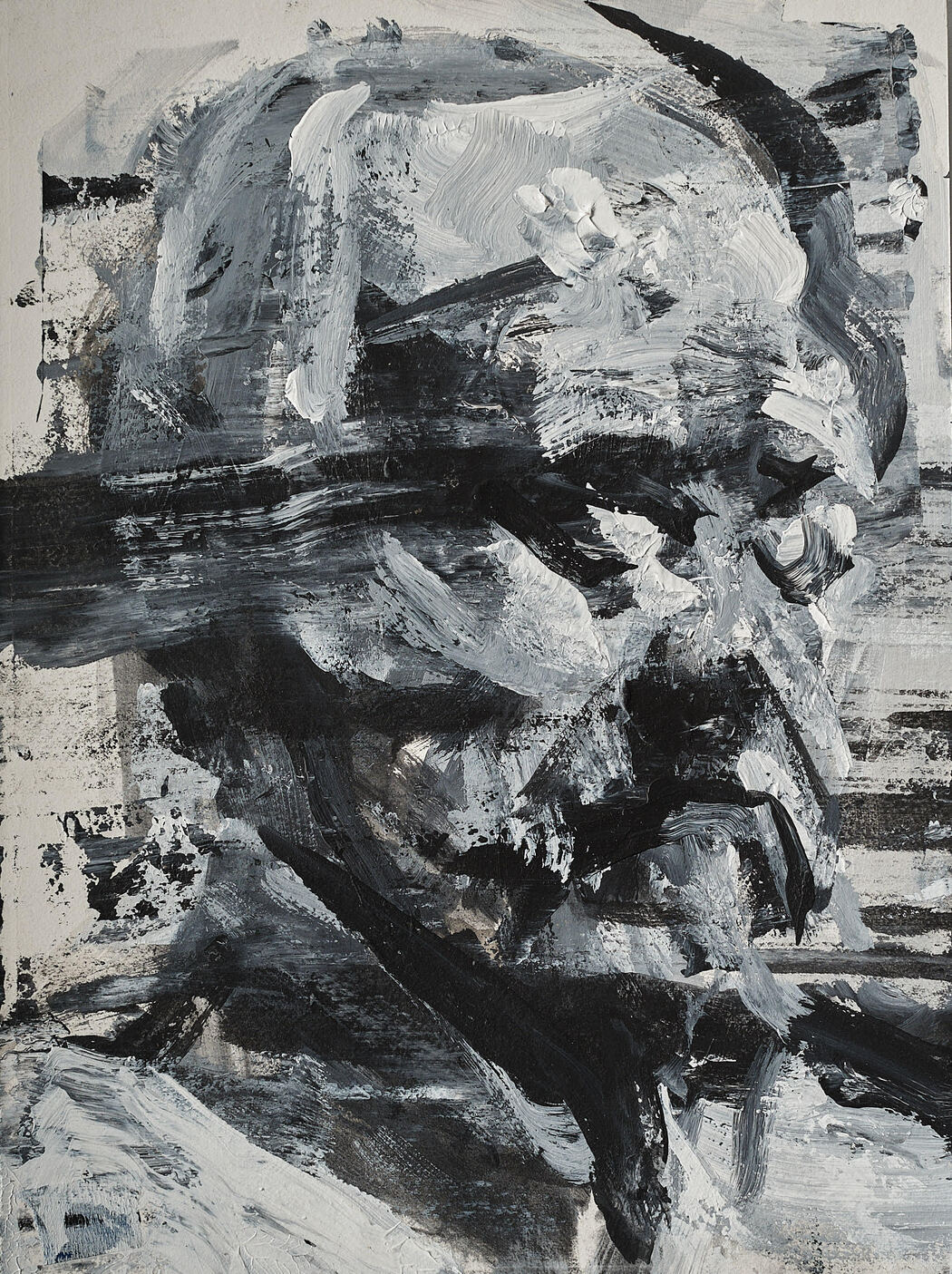

Harry Simmonds

Your portraits are deeply expressive yet entirely monochromatic. What draws you to working exclusively in black and white?

Although my work is figurative, it’s vital to me that the marks possess a spontaneity and life of their own — something that allows the paintings to function abstractly as well. Black and white helps me concentrate on that. When I first began making figurative work, I simplified things by focusing solely on drawing, starting with charcoal. Over time, I introduced Indian ink and eventually white paint. I’m not opposed to using colour one day, but I don’t yet feel I’ve exhausted what black and white has to offer.

How do you choose your sitters? What qualities or energy do you look for in a person before painting them?

My current sitters are professional life models who approached me, so I didn’t actively choose them — I didn’t even know what they looked like before they arrived. The more time I spend looking at a model, the more I discover in their features, and they usually become increasingly compelling to me as subjects. I tend to pick up on how the model is feeling during the sitting — if they’re uncomfortable, I can often sense it. Professional models are particularly helpful because they’re used to holding poses for long periods.

Many of your brushstrokes seem impulsive, raw, even chaotic — yet they build incredibly coherent portraits. How do you balance control and spontaneity in your process?

To achieve that kind of mark-making, I need to enter an intense, focused state where I’m no longer self-conscious — where the marks emerge almost automatically rather than through calculated effort. Psychologists refer to this as a ‘flow’ state. It works best when I paint with feeling and instinct, rather than intellect alone. For me, painting is a process of discovery. I want to surprise myself. That’s why I often relinquish some control — to allow for chance and accident.

Do you see your work as more psychological or emotional? What are you hoping to reveal about the sitter — or the viewer?

I think the best portraits do more than represent an individual — they also say something about humanity. Not symbolically or allegorically, but through a different way of seeing. Often it’s because they avoid sentimentality that they feel more truthful. Each time I look at a model, I try to imagine it’s the first time I’ve ever seen a human being. That visual shock is what I aim to communicate. I hope the final painting carries a presence that feels almost physically tangible.

The artist’s role, I believe, is to create something that others can connect with — to move them emotionally — but also to reimagine the world and help viewers see things differently.

How important is abstraction in your figurative work? Do you consider your portraits faithful likenesses or emotional interpretations?

I don’t really think in terms of likeness — it’s the model’s presence that matters to me. I believe that to make a subject feel more real, some level of abstraction is necessary. Take Madame Tussaud’s waxworks: they’re incredibly detailed and accurate, yet they can feel oddly lifeless. I aim for something that feels more alive than literal.

Could you describe your process — from the moment someone enters your studio to the final brushstroke?

I typically have many paintings of a single model going at once — sometimes as many as ten — and I work on all of them in a single session. I ask the model to set a timer and hold each pose for a few minutes before moving on to the next, looping back again at the end. This fast pace forces me to work with urgency.

The process is very physical — my sitters often say it looks more like fencing than painting! I use all kinds of tools: brushes, rags, knives, spatulas, feathers, fingers, syringes — whatever produces the right mark.

It’s easy to go blind to mistakes after staring at a painting too long, so I often check it in a mirror to see it with fresh eyes. I paint on paper, which I love for the way it absorbs paint. When the surface becomes too overworked, I tend to abandon it and start again with the same pose. So although the paintings may appear to be done quickly, they usually evolve over many days, weeks, or even months.

Sometimes a painting ends with a kind of crescendo — it’s clearly finished. Other times, it feels like you’re simply walking away. Painting is a bit like gambling: you have to decide whether to settle or take a risk to push it further, even if that means losing what you’ve already achieved. The best results often come from being willing to take that risk.

What role does discomfort, distortion, or ambiguity play in your compositions?

It’s essential that the paintings function not just as figurative images, but also as abstract compositions. I’ll often look at them upside down to assess the quality of the marks or the balance of the form. I don’t set out to distort — I just do whatever I feel the painting needs in order to feel more alive.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.