Ian Ball

Year of birth: 1980.

Where do you live: Niagara Region, Ontario, Canada.

Your education: Bachelor’s degree in Dramatic Arts, History of Art and visual culture.

Describe your art in three words: Confused but committed.

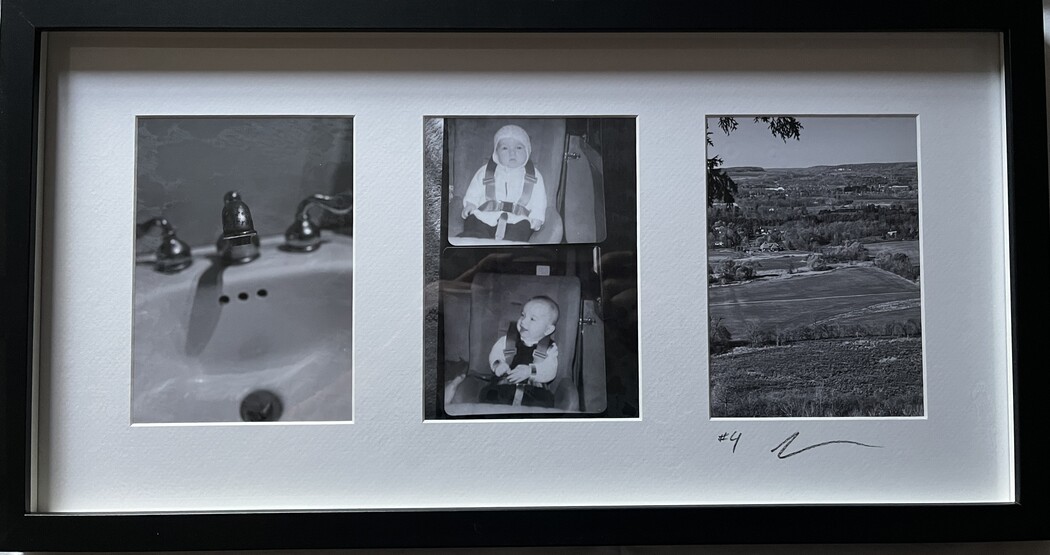

Your project seems to explore the complexity of identity through seemingly unrelated images. Can you explain how you chose these particular moments to capture, and what they represent for you?

The most challenging part of this project was deliberately choosing images between which I could find no obvious connection. I’d photograph anything that caught my attention, no matter how trivial, and then try to select three that felt entirely detached from one another—metaphorically disconnected from my lens. To me, they reflect the viewer’s power to construct meaning where none was intentionally placed.

It’s a bit of a cliché, but we really are all Frankenstein’s monsters—stitched together from moments, people, places, and fragments of influence. Those patchwork parts don’t just make us who we are; they dictate how we interpret the world. I can only ever see through the eyes of my own monster, which is why I find it so compelling to witness how others assemble meaning from the same pieces.

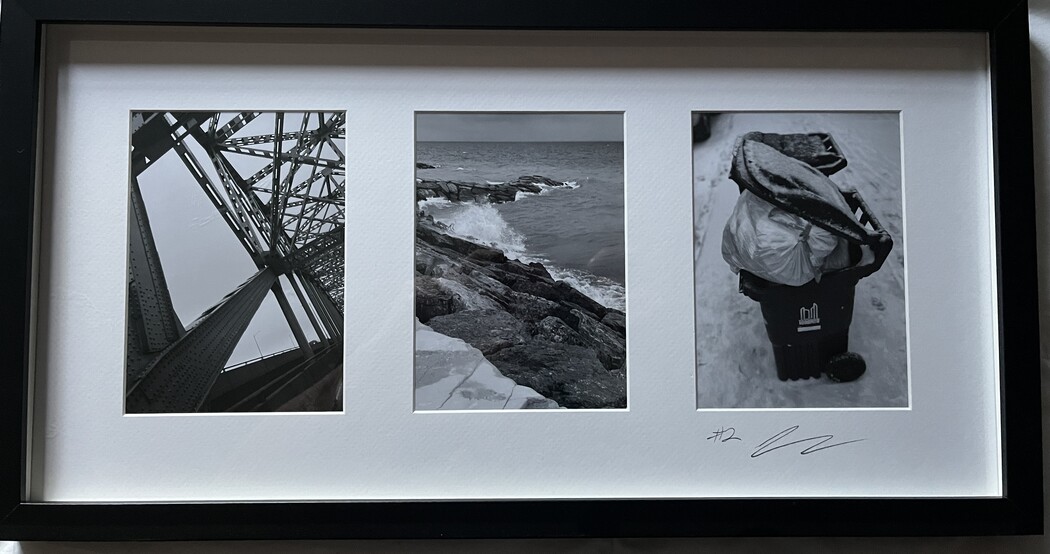

The images you have presented blend nature and industry. What are you hoping to convey by juxtaposing these elements?

While the environmental message is hard to miss, I’d like to think there’s also room to contemplate the strange aesthetics at play—to see both the beauty and the quiet horror in what we’ve built. Nature’s elegance speaks for itself; it doesn’t need my endorsement. But I’ve caught myself staring at a crumbling factory wall with the same kind of awe—marveling at the ambition it took to create it, and, oddly, comforted by the evidence of its decay.

There’s something poetic in that impermanence. Our ingenuity may be vast, but so is our fragility. The damage we’ve done won’t outlast us forever—and maybe, in a bittersweet way, that’s part of the hope.

How do you approach the concept of solitude versus community in your work? Are these themes personal, or do they reflect broader societal trends?

Without a doubt, it’s personal. Solitude feels less like a choice and more like a default setting—woven into the fabric of how I think and create. Collaboration has its place, and I value community deeply, but when it comes to generating ideas, I find that quiet isolation acts as a kind of intellectual catalyst.

It’s not that my work is explicitly about solitude, but it rarely exists without it. The silence isn’t just background noise—it’s part of the process. So even when the subject matter doesn’t shout “aloneness,” it still echoes with the conditions under which it was born.

Your work invites the viewer to make their own connections between the images. What do you hope people will take away from the contrasts you’ve explored?

If there’s one thing I’d hope someone takes away, it’s permission—the permission to engage with an image on their own terms. We’ve gotten used to letting images pass over us like weather: noticed, but not questioned. Or worse, we second-guess our reactions, assuming there’s a “right” way to see, tucked somewhere in a textbook or gallery guide.

Yes, a formal education can give us the tools for a more nuanced take—but intuition isn’t a lesser form of understanding. Sometimes an image resonates not because it checks historical or theoretical boxes, but because it hums at the same frequency as something inside us. That doesn’t make it less valid. If anything, it makes it more alive.

You mention that your work reflects a vast and multicultural world. How do you think your local environment in Niagara influences your artistic practice?

I spent years working in Niagara Falls, where tourism isn’t just an industry—it’s part of the landscape. In a place like that, you get this fascinating convergence: people from every imaginable background, all gathered to witness the same phenomenon. It always reminded me of Kurosawa’s Rashomon—different eyes on the same cascade, each bringing their own story to it. At its core, it’s just water tumbling off a cliff. And yet, for one person, it might be a spiritual epiphany; for another, just a photo op. The sublime and the underwhelming coexisting in the roar of the same waterfall.

What role do performance pieces play in your practice, and how do they complement or contrast with your photographic work?

There are a lot of performance artists that I find endlessly inspiring, and I think I get a lot more energy from that creative sphere than most. For instance, there is something amazing about Bruce Dunlap shooting Chris Burden with a .22 for a performance piece. While my photographic work has very little in common with the likes of Burden, I feel a weird kinship with the audacity of the whole endeavour.

Is there a specific philosophy or belief that guides your creative process, or do you approach each project with a different mindset?

I try to approach everything differently, but if I narrowed it down to a singular philosophy, I’d look to David Lynch, who said, “I don’t know why people expect art to make sense. They accept the fact that life doesn’t make sense.” I love this quote, and I love having my understanding of a thing I made, and seeing people come to their separate understanding and knowing that we are all hitting the mark, just from different angles.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.