Xufei Qiao

Year of birth: 1994

Where do you live: Beijing

Your education: MA in Textiles at Royal College of Art

Describe your art in three words: Nature, Textile motif, Cultural heritage

Your discipline: mixed media

Website

Your art blends natural elements and traditional textile design techniques. How do you manage to fuse these influences so seamlessly, and what is the significance of using these particular materials?

First, I believe artists incorporate many of their life experiences into their work, which can manifest as concrete objects and symbols or as abstract feelings. For me, the boundary between drawing and textile print has always been blurred—at least technically speaking, both involve leaving marks on paper with brush and pigments. During my self-taught journey in drawing, some of my working methods as a designer were naturally integrated, such as using techniques from textile design to develop color and texture and often researching design history for reference. Regarding natural elements, I’ll address that in the following questions.

You mentioned the role of your rural seclusion during the pandemic in shifting your focus from textile design to fine art. How did that time influence your artistic development, and how is it reflected in your current works?

Being a fashion and textile designer requires adapting to a rapid pace and intense pressure. I often compare myself to an image processor—a machine that analyzes, transforms, and processes countless inspirational images into print designs. When I left the city to live in a quiet country house, I was surrounded by the sky, rocks, trees, and flowers. I would often drive to canyons to sketch, draw trees and landscapes, and see more tangible objects. This feeling was completely different from designing, and it made me rethink what I really loved. When we get busy in our daily lives, it’s easy to ignore our deeper needs. People have asked me whether my personal style is closer to abstract energy or rational accumulated effort. After experiencing a year of pandemic lockdown, I don’t think my work underwent a dramatic transformation – I’ve just become more sensitive to my current creative state and emotions and can now engage more actively in creating works of any style.

Xufei Qiao | Portrait of Cockatoo

Xufei Qiao | Portrait of Cockatoo

In your ‘Night Park Slide’ series, you focus on the uncanny qualities of playground slides under dim streetlights. What was it about this particular subject matter that drew you in?

The ‘Night Park Slide’ series began with a spontaneous night ride. I lived in a university neighborhood where the streets maintained a quiet, peaceful atmosphere at night. As summer was just beginning and the evening weather was comfortable, I started cycling around the area with my sketchbook and pastels, stopping to draw whenever I encountered a nightscape I liked. Rather than being a purposeful sketching activity, it was more like a game of rediscovering the city. My encounter with the slide happened in a small urban forest park, where a large slide built from stone and wooden posts sat before me like a castle. I could imagine countless children playing and laughing there during the day, but at that moment, the park was so silent and solemn. I captured this striking contrast in my drawings, and this experience had a subtle but lasting impact on how I view things, so much so that I later made multiple nighttime visits to different park slides, seeking inspiration.

Your use of color in these works seems deeply intuitive. Can you elaborate on how you select and blend colors in your compositions, especially when relying on intuition and grayscale values?

When handling colors, one of my principles is to try to make each stroke a different color. Unlike studio painting, my sketching primarily uses oil pastels and soft pastels. Rather than mixing colors, I work directly with the materials’ natural hues. I tend to divide things into many small sections and fill them with color; for instance, I might paint concrete tiles in a variety of colors, thinking “What if there’s green next to pink, and then black next to that – wouldn’t that be fun?” letting these colors dance on the paper. What’s even more interesting is when the environment is so dark that color hues become indistinguishable – then all I can rely on is the variation in grayscale values. What I do is shuffle my pastels and ensure that adjacent color blocks have different grayscale values when coloring. This creative approach brings surprising results, making me realize how much we typically rely on subjective judgment when choosing colors. For me, it’s a new challenge and a way of self-discovery.

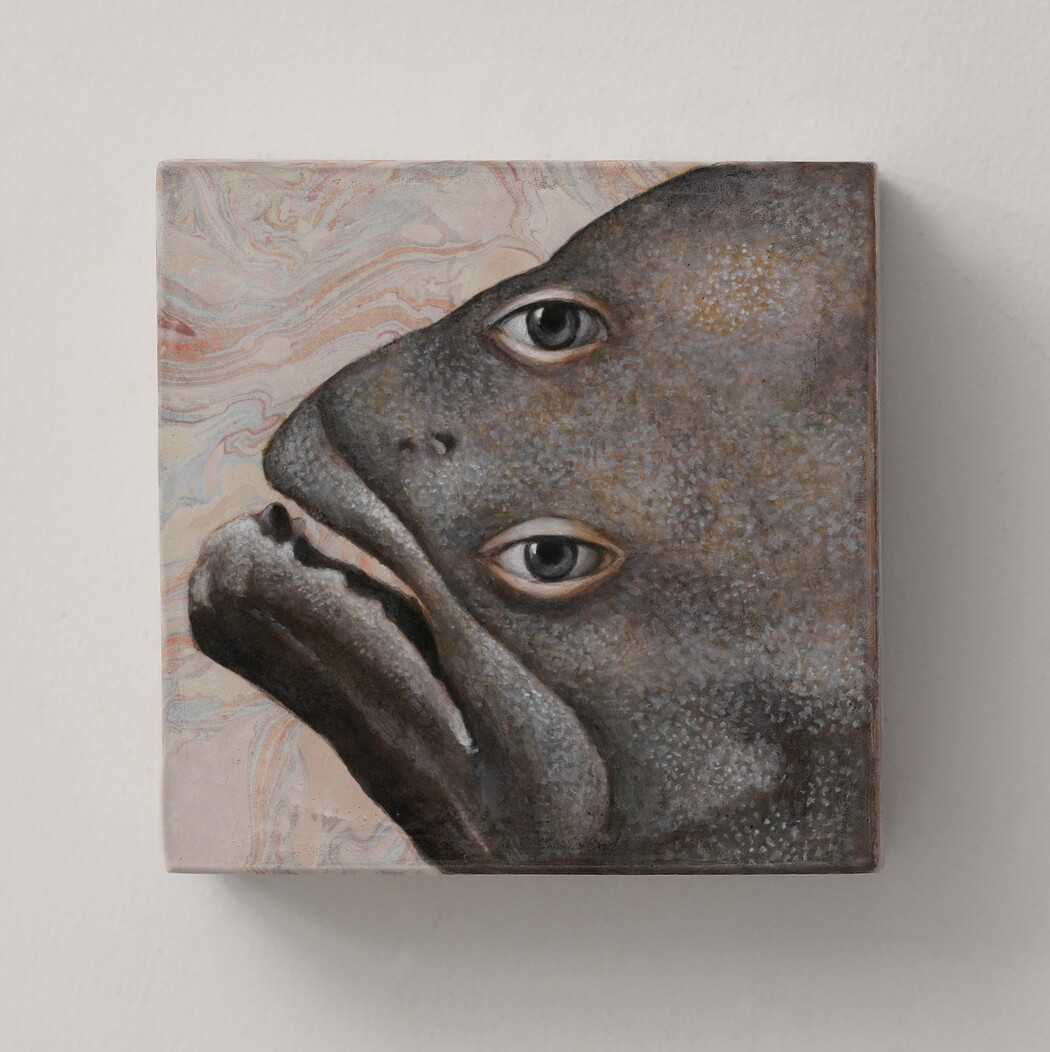

Xufei Qiao | Portrait of Flatfish

Xufei Qiao | Portrait of Flatfish

Could you share more about your experience growing up in a family of agricultural engineers and how that influenced your approach to observing and documenting natural phenomena?

I’ve always felt that observing the growth of living things is a magical experience. When I was seven years old, I went on field trips with my father, who is an agricultural machinery researcher. While he and his fellow researchers were collecting crop samples, I would dig up rhinoceros beetle larvae from the soil, arrange them by size in a row, and imagine what they would look like when fully grown. Around this time, I started documenting plants and animals in my surroundings, particularly when I moved to Montreal during fifth grade. I spent incredibly long hours on the elementary school lawn, creating a mushroom guide where I sketched every kind of mushroom I could find. I believe drawing is also a form of documentation, but unlike botanical illustration, it includes more complex information beyond just recording appearance – it captures the artist’s perspective, mood, metaphors, and more.

Your works often explore the interplay between cultural memory and nature. Can you talk about how the ice plum pattern, for instance, relates to your exploration of these themes?

A place’s natural landscape influences its visual culture. On a crisp winter’s day, I wandered through the gardens of the Old Summer Palace, where nature itself seemed to paint an eternal masterpiece. Plum blossoms swayed beneath a cascade of winter light, their golden reflections transforming each branch into shimmering threads of summer streams. Nearby, cracks in the frozen lake echoed the iconic “ice plum” pattern from the Qing Dynasty—a design where intricate ice-crack motifs are adorned with plum blossoms. My recent work, Ice Plum Blossom, builds upon this historical foundation. Through meticulous recreation of the ice-crack pattern, I embarked on an intuitive journey of sensation, memory, and philosophy, echoing the flow of an oriental garden.

Having lived in multiple cities, how does your multicultural background influence your approach to art, especially in terms of bridging Eastern philosophical traditions with contemporary artistic practices?

Due to my family circumstances, I frequently moved between different cities starting in elementary school. Remarkably, I never felt confused by culture shock; instead, I found many interesting aspects to it. On one of my design projects, I researched both the Classic of Mountains and Seas and medieval European monsters, discovering that despite these regions having no contact at the time, there were surprising similarities in how they created these mythical creatures. In my understanding, Eastern philosophy emphasizes the fluidity and undefined nature of things, similar to the Zen concept of “a world in a grain of sand.” I hope to engage in more discussions on this topic and further affirm my artistic language.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.