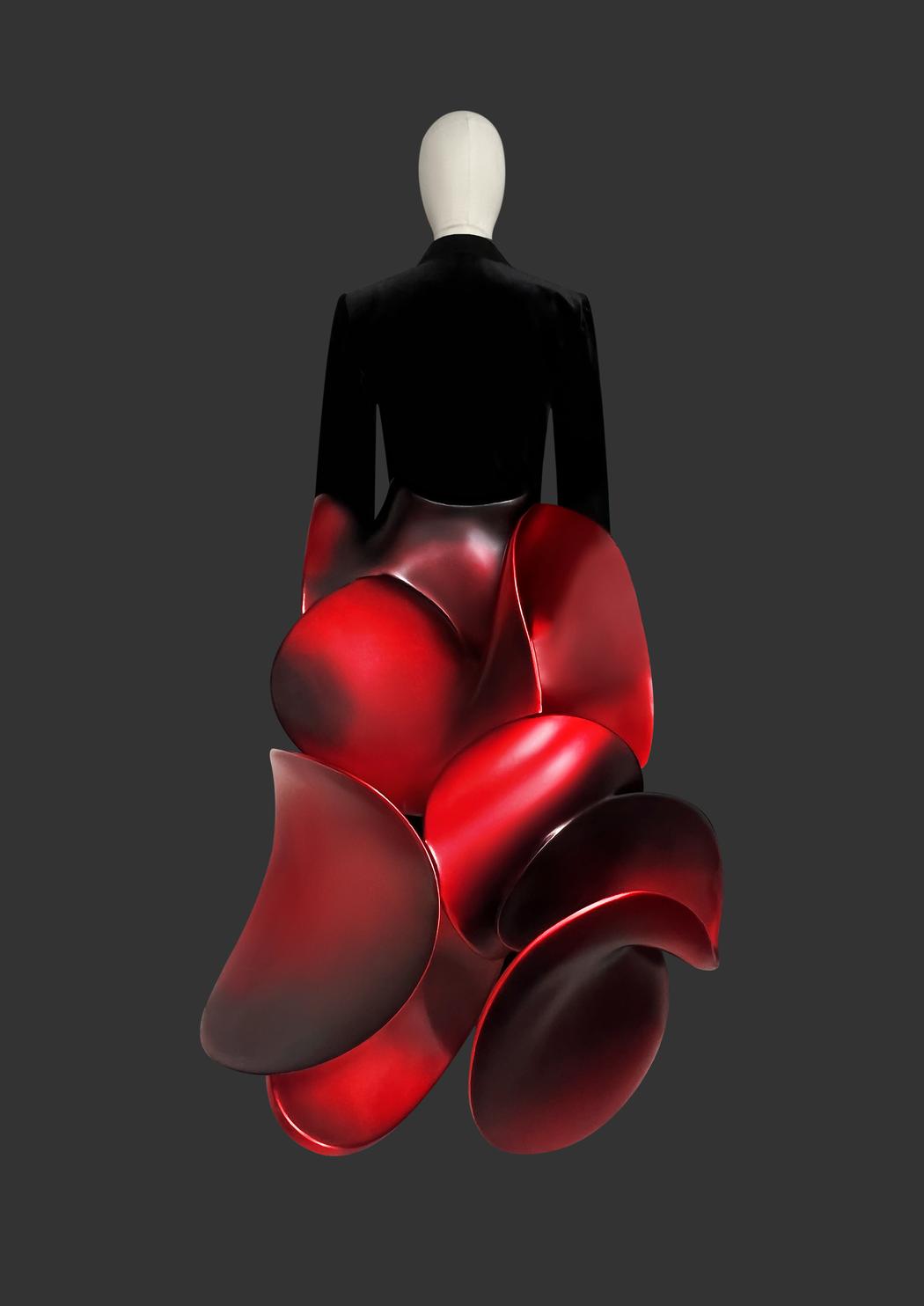

Yumeng Li

Your education: B.A. in Mathematics & Economics (UCLA); M.A. in Fashion Design (Academy of Art University, San Francisco)

Describe your art in three words: Emotional · Inclusive · Experimental

Your discipline: Avant-garde fashion / Gender-fluid

Your practice merges traditional garment construction with advanced digital workflows. How do you balance the tactile, physical aspect of fashion with the precision and abstraction of parametric modeling and 3D simulation?

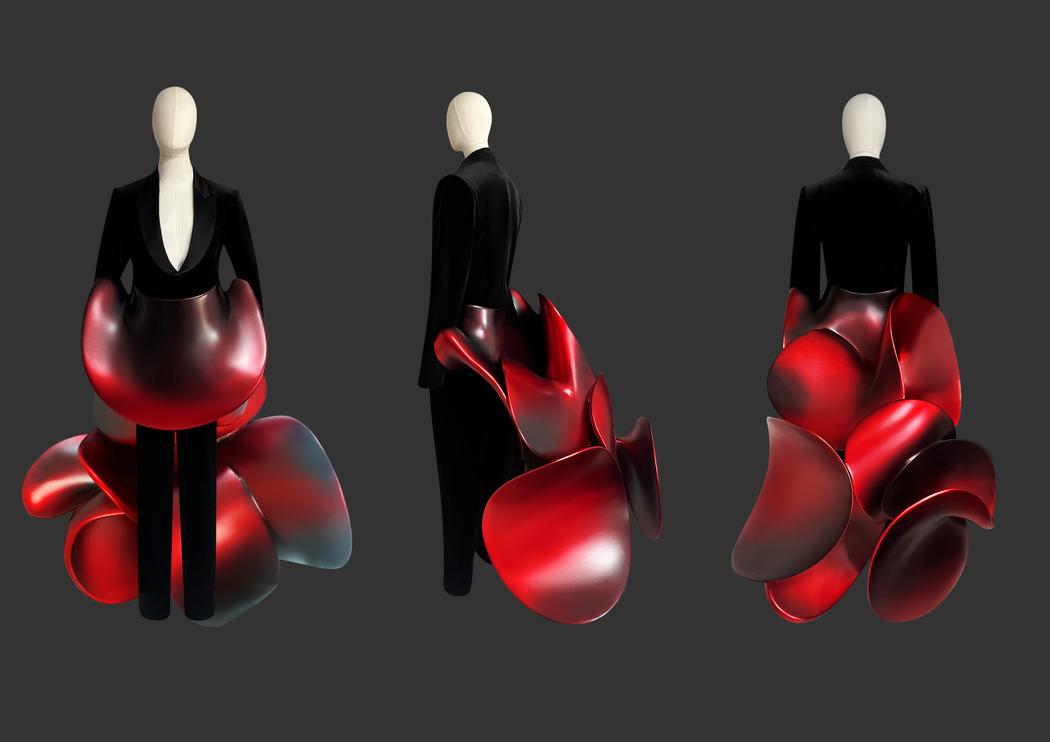

For me, balancing tactility with digital precision is a closed feedback loop. I begin with draping experiments on a 1:4 scale dress form, using elastic fabric with fish bones to build silhouette and volume by hand. This stage is essential because touch makes structure legible: I can immediately read tension, angles, collapse, and support, and quickly identify the most expressive points of the form.

Once the proportions are resolved, I build a full-scale digital avatar in my modeling software based on the measurements of the actual dress form, ensuring a one-to-one match. Using the logic of the 1:4 prototype as a reference, I reconstruct the structure on the digital body, align key connection points, and calibrate dimensions and tolerances precisely. Because the model is executed to real-world measurements, the 3D-printed components translate accurately at full scale and can be fitted directly onto the dress form, reducing repeated toile iterations and size adjustments. In short: draping finds the truth, computation delivers it.

Your collections often react to natural phenomena—light, movement, organic growth. How does nature shape the emotional or philosophical foundation of your work?

For me, nature is not a source of imagery but a practical framework for thinking about change. Light, movement, and growth recur in my work because they remind me that form is never fixed; it is continuously shaped by time and by the act of looking.

Light is central. The same piece can be perceived differently as angles and distances shift—echoing Su Shi’s insight that each viewpoint reveals another truth. I approach this with a Cubist sensibility: an object is constructed through layered perspectives rather than a single image. I use transparency, variations in sheen, and structural lines so that, as light changes, the work generates shifting visual and emotional states, and the viewer’s movement becomes part of the composition.

Movement and growth turn garments into events. Walking and breathing redistribute tension, opening folds and collapsing volume; at the micro level, I take cues from molecular motion, where change emerges from countless small movements. Growth implies repetition, variation, and repair, which leads me toward modular, reconfigurable systems. Ultimately, this approach allows a work to hold past, present, and future versions at once—embracing uncertainty while seeking new forms of order and beauty.

In your designs, forms are modular and reconfigurable. What draws you to systems that allow continuous transformation rather than fixed silhouettes?

I’m drawn to modular, reconfigurable systems because of a metaphysical concern: I’m less interested in what a garment looks like as a final image than in why form holds and how it comes into being. A fixed silhouette tends to present one definitive answer, while a transformable system brings attention to the underlying structure—connections, constraints, tension, boundaries, and replaceable relationships. In this sense, form is not an endpoint; it is a temporary manifestation of a set of relations at a specific moment.

When components can be detached, rotated, and reassembled, each configuration becomes a different “version” of the same proposition. The garment shifts from an object to a process, where meaning is produced through change rather than permanence. This also allows the body, emotion, and context to participate in shaping the work: movement or situation can alter how the system resolves itself on the body. For me, continuous transformation is not a technical display; it is a way to speak about the nature of being and becoming—how instability, multiplicity, and time are intrinsic to form.

How does real-time emotion and bodily movement influence your design process? Do you consider the garment as something that changes with the wearer’s psychological state?

Real-time emotion and bodily movement are central variables within my practice. Within my design philosophy, the garment is not conceived as a static covering, but as a “second skin” that breathes in dialogue with the wearer. In my previous collection on involution, the work was anchored in a single affective condition: anxiety—a tightened pressure produced by constant competition and self-imposed demand.

For this reason, emotion is embedded into structure and kinetics. Anxiety is articulated through wrapped, rotating, and compressed curved surfaces, producing a silhouette that reads as if it is continually drawn inward by a high-speed spiral—constricting, pressing, and resisting full release.

Ultimately, the aim is to translate internal affect into a visible, time-based language: not concealing the body’s anxiety, but allowing it to register with clarity through silhouette and the garment’s shifting exterior form.

You work across CLO3D, Touch Designer, and Nomad Sculpt. How does each tool contribute to different stages of your creative workflow?

Nomad Sculpt serves as the entry point of my digital process—functioning as a “sketchbook” and “sculpting clay.” When a concept is still ambiguous, the form is developed directly in 3D to rapidly shape silhouettes and explore organic volume, exaggerated folds, and tactile surface qualities. Its purpose is to capture the raw aesthetic impulse and emotional tension, establishing a distinct visual DNA for the collection.

CLO3D then translates these intuitive forms into a wearable structural system—a “digital tailoring studio.” Within this stage, patterns are constructed with rigor, and fabric parameters are defined. In effect, it functions as a digital toile: enabling an early view of the finished look, calibrating proportion and stress points, reducing repeated pattern corrections and sampling, improving production efficiency, and ensuring that the concept resolves into an ergonomic, wearable garment.

Touch Designer advances the work from static form into time-based systems—a “digital magic lab.” It is used to generate and drive dynamic visuals by translating sound, bodily-movement data, or algorithmic noise into patterns, prints, textile-like textures, and rhythmic image behavior.

Your brand YUN MOONMOON has a strong visual identity rooted in softness, futurism, and functionality. How did this aesthetic language develop over time?

YUN MOONMOON’s visual language was not something “set” from the beginning; My work treats clothing as an emotional medium and aims to articulate a gender-neutral bodily language.

This aesthetic vocabulary has grown out of continuous knowledge accumulation and multidisciplinary training. Study across different fields has helped build structural thinking and systems logic; everyday observation of posture, stress responses, and social dynamics provides concrete bodily evidence; and engagement with art, literature, and painting offers narrative methods and art-historical references—so the work does not remain at the level of styling, but points toward deeper emotional and cultural contexts.

Within this approach, “softness” is understood as an empathic capacity—an ability to sense and hold another person’s emotional state, rather than merely a tactile quality. It aligns with an Expressionist sensibility: not pursuing objective representation, but making the intensity, tension, and vulnerability of inner experience visible, allowing the garment to function as an interface that carries feeling.

For me, “futurism” is primarily a pathway for expanding what clothing can be: ongoing experimentation with materials, forms, and cross-media integration, supported by digital tools that translate emotion into structural language while also shortening development timelines and improving production efficiency. At the same time, “functionality” is refined through repeated real-world testing. Clothing is not only decorative; it should include human-centered features—serving the body through wearability, mobility, adjustability, and support—so that emotional expression can be lived with and experienced over time.

Your work has appeared at New York and Shanghai Fashion Weeks. How do runway presentations influence the way you think about scale, movement, and the narrative of your collections?

Runway experience at New York and Shanghai Fashion Weeks has made one thing clearer: on the catwalk, a garment is not a static display, and the process pushes the design approach from individual looks toward the orchestration of an overall narrative.

In terms of scale and sequencing, rhythmic fluctuation is treated as part of the design—for example, the pacing of model entrances, a progression in color from light to dark, and alternating several relatively restrained looks with a more exaggerated silhouette.

In terms of movement and interaction, a runway show becomes a dynamic image completed together with the audience. The beat of the music, the model’s stride and pauses, and the instant of a turn all change how the garment is perceived.

In terms of narrative, the collection is approached as a time-based expression: an emotional curve is built through musical atmosphere, the model’s physical language, and the progression of silhouettes, so the show itself becomes a way of telling the design story—with fluctuations, momentum, a climax, and resolution.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.