Aisha Fatima

Where you live: London, United Kingdom

Your education: BA Honours in Social Anthropology and Marketing, SOAS University of London

Describe your art in three words: Intimate · Reflective · Interconnected

Your discipline: Acrylic painting and mixed media with a focus on conceptual and cultural themes

Aisha Fatima | A Vibrant Sunset Tale

Aisha Fatima | A Vibrant Sunset Tale

How did your artistic journey begin, and what led you to explore painting as your main form of expression?

My journey began in childhood, when art felt like the most natural way to understand the world around me. I grew up surrounded by stories, textures, and visual traditions that shaped my curiosity early on. I still remember drawing brand logos as my first sketches. Ray-Ban was the first one. Then Nike. Then Tag Heuer. After that I started drawing Audi and Mercedes logos and obsessing over getting the lines symmetrical so those triangle-like shapes looked perfect. It is strange how vividly I remember those moments, but I suppose that is what makes an artist. Those early drawings became my personality, my instinctive language. Art has always been the thing people associate with me, the thing I turn to in my free time, and the dream I quietly hope grows into a widely recognised career.

Painting eventually became my primary language because it allows me to work slowly and intuitively. The process of layering colour, texture, and detail feels very close to the way memory forms. It lets me capture the emotional and cultural nuances that words often miss.

You have described yourself as a self-taught artist. How has that shaped your creative freedom and perspective compared to a formal academic path?

Being self-taught has given me the freedom to experiment without the weight of a prescribed artistic lineage. Growing up in South Asia, pursuing art is often a battle. It is treated as a hobby rather than a career, and parents worry because making a living from it can be difficult. They want stability for us, and they are right in their own way, but that tension makes the pursuit even more personal and resilient.

This independence also encouraged an instinctive approach to technique and style, which later blended with my academic background in social anthropology. This mix of self-direction and research creates a practice that is deeply personal yet grounded in cultural inquiry. I explore ideas at my own rhythm and follow themes that feel authentic rather than expected.

Aisha Fatima | Wick And Weight

Aisha Fatima | Wick And Weight

Much of your work focuses on the idea of cultural intersections. How do you usually discover or identify these visual and emotional parallels between different traditions?

I find these intersections through close observation. The smallest details often reveal the strongest parallels. A pattern on a shawl can echo the geometry of a building, or a fragment of wood carving can mirror the texture of a distant landscape. My anthropological lens helps me recognise these shared resonances.

Before studying anthropology, I used to create more trendy work to make it on social media, like pop art, celebrity portraits, or patterns that fit popular transitions. After anthropology came into my life, everything shifted. I felt a deep need to add meaning and depth to my art, to explore identity and memory rather than just aesthetics. I look for the ways different cultures hold memory, beauty, and belonging in material forms. These quiet connections become starting points for my paintings.

How does your Kashmiri heritage influence your artistic vision and the stories you choose to tell?

My Kashmiri heritage is the foundation of my visual vocabulary, and so much of my art begins with wuchun – the quiet act of seeing – and unfolds through layers of yaad and zan, where memory and understanding shape how a rukhs or an object is represented on the canvas. My work is guided by the textures, colours, and symbols I grew up around. I often draw from memories of home, traditional craftsmanship, and the emotional significance of objects like pashmina threads, rop (copper) samavars, wicker kanger (clay pot with hot embers inside, encased in a decorative wicker basket.), and the soft florals of a pheran cuff.

Being part of a diaspora adds another layer. It brings a sense of longing and sensitivity to what is easily overlooked. My art becomes a way to honour what endures and to record what risks disappearing.

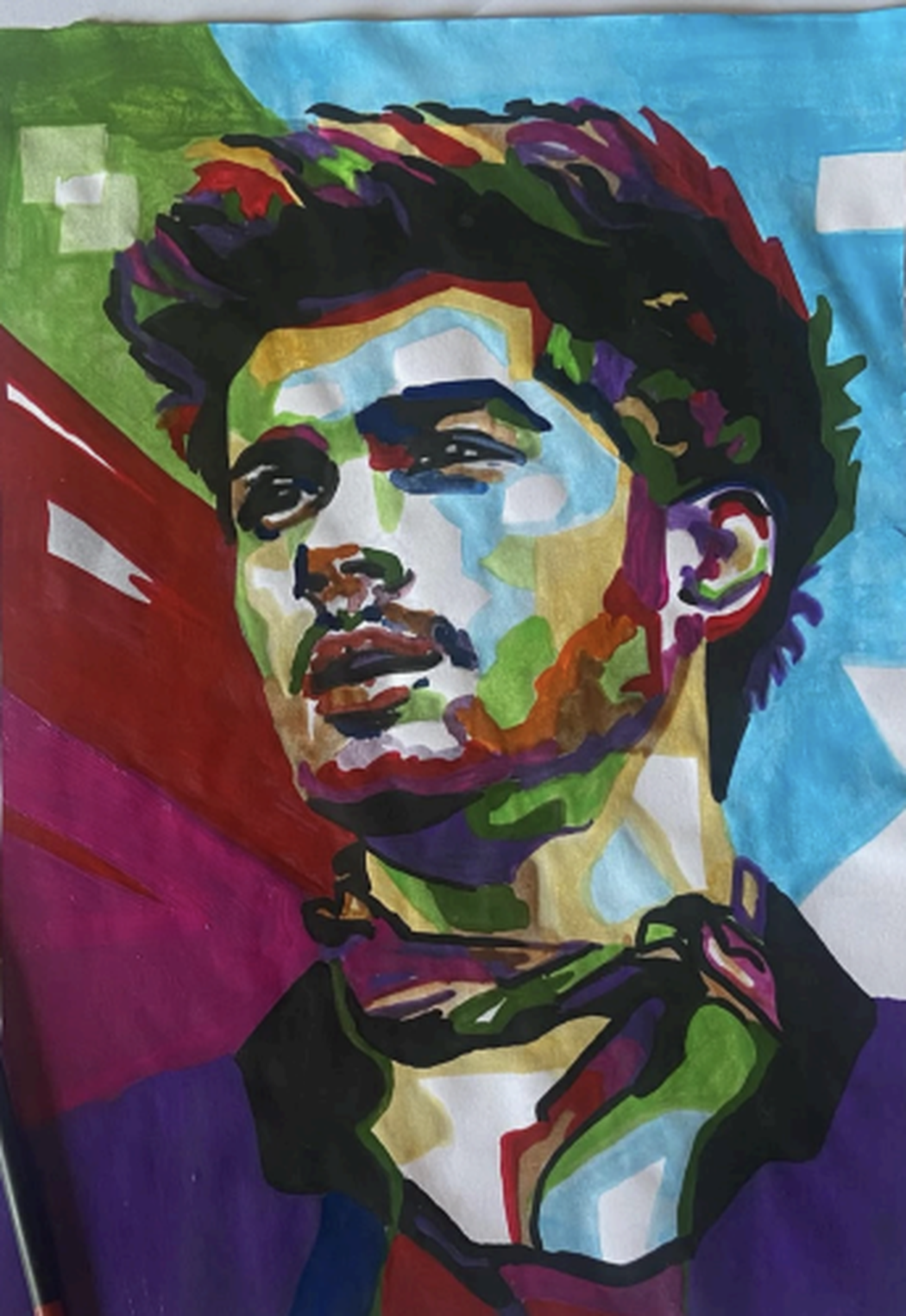

Aisha Fatima | A Pop Art Rebellion

Aisha Fatima | A Pop Art Rebellion

Your project Microcosms reimagines overlooked fragments like textiles or architectural details. How did this idea emerge?

Microcosms emerged from a desire to look closer at the mundane. I realised that the smallest details often carry the deepest stories of place and identity. A single thread, a corner of carved wood, or the worn edge of an umbrella handle can hold entire histories within them.

I wanted to create a project that treated these fragments as worlds in themselves. The concept also draws from anthropology, where the micro can reflect the macro, revealing how personal and collective narratives intersect.

Over time, I also became fascinated by how these fragments hold emotional weight. A copper samavar’s rim reminds me of gatherings, warmth, and conversations that never repeat the same way. A tile edge can echo the geometry of a place I have known since childhood. These details feel like quiet keepers of yaad, small containers of memory that resist being forgotten. Microcosms grew from that instinct to slow down, to honour what the world rushes past, and to build a visual language out of the intimate.

What do these small and familiar elements reveal to you about identity and memory?

They reveal how identity is built from accumulation rather than spectacle. Memory lives in the quiet and the familiar. These fragments show how cultural inheritance is carried through touch, repetition, and use. They remind me that belonging is often found in subtle gestures and material traces. When magnified, these elements become emotional landscapes that hold both intimacy and universality.

What fascinates me most is how these tiny details can spark entire internal worlds. A thread, a hinge, a woven line of wicker, or the curve of an arch can trigger both personal and generational memory. They reveal how identity is layered, like paint, with one stroke resting upon another.

In many ways, Microcosms is also about resisting erasure. In a fast moving world, these elements become anchors. They whisper stories of migration, home, longing, and continuity. They teach me that memory is not always loud. Sometimes it survives in the smallest corner of a surface, waiting for someone to notice.

Aisha Fatima | A Dance Of Color And Chaos

Aisha Fatima | A Dance Of Color And Chaos

How do you see the role of art in promoting empathy and cross-cultural understanding today?

Art creates space for slow looking. In a world that moves quickly, this is a powerful invitation. When viewers take time to engage with the details of a painting, they begin to recognise their own memories in someone else’s symbols. I believe art can soften the boundaries between cultures by highlighting shared textures, emotions, and human experiences. It becomes a quiet form of bridge building, where empathy grows through reflection rather than instruction.

I also think art allows people to enter another culture without defensiveness. When someone encounters a Kashmiri motif, a fragment of a pheran cuff, or the curve of a masjid arch in my work, they are not being taught something. They are being invited to feel something. That shift from explanation to emotion builds a different kind of understanding.

In its simplest form, art reminds us that we are all shaped by memory, by longing, by fragments of home. That universality is what creates empathy. Art becomes a meeting point where the intimate becomes shared and where difference becomes connection.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.