Lea Laboy

How did your transition from academic oil painting to conceptual and psychogeographic art occur?

Conceptual art is like a shadow that accompanies my oil painting. One feeds the other and forms an integral whole. However, I’ve noticed that when my faith in humanity wanes, I return to conceptual work. The only change is that previously, during such periods, I created Performance that assumed viewer interactions, whereas now I enter a space that influences me, presenting the finished product to viewers—an object. This is a completely different creative process than performance, though close to painting if we accept the psychographic assumption that the city is a constantly changing “landscape of dreams”.

Your recent work explores the intersection between psychogeography and oriental architecture. How do these two seemingly distant worlds connect in your artistic vision?

Psychogeography, generally speaking, is a science that examines how the urban environment—its architecture, layout, and atmosphere itself—influences the emotions of individuals. Therefore, every location is a potential site for fieldwork.

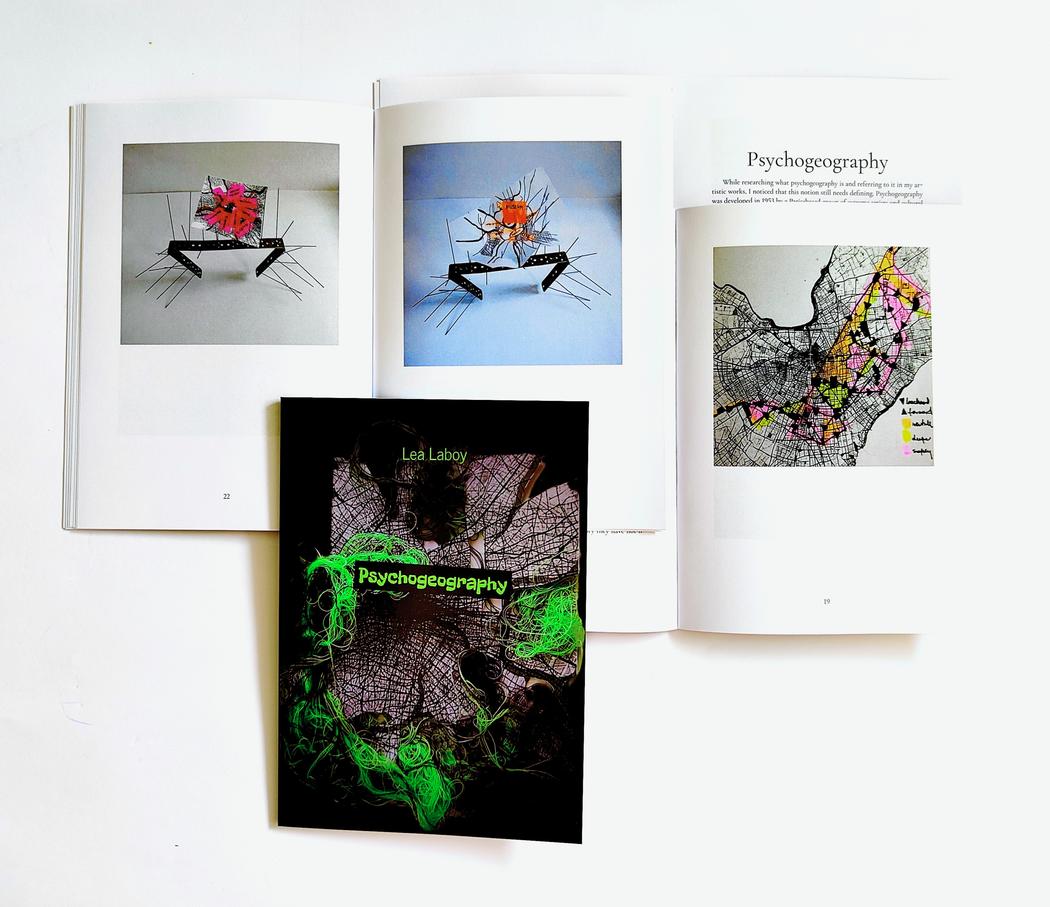

Lea Laboy | Psychogeograhy

Lea Laboy | Psychogeograhy

Could you elaborate on the influence of 1950s psychogeographic practices — particularly those inspired by Guy Debord — on your recent projects?

Drifting is certainly the key practice I’m referring to, which in itself is the essence of psychogeography. Let’s also remember that psychogeography is a field that draws from surrealism, utilizing its techniques, and therefore focuses very strongly on the sphere of emotions, which I have also adopted. I certainly utilize objective chance, relying on coincidences.

What role does photography play in your artistic method — is it documentation, or an autonomous form of expression?

Photography in my work serves only as a form of documentation. Sometimes a moment is not enough to capture with a brush, but enough to make a single click with a camera.

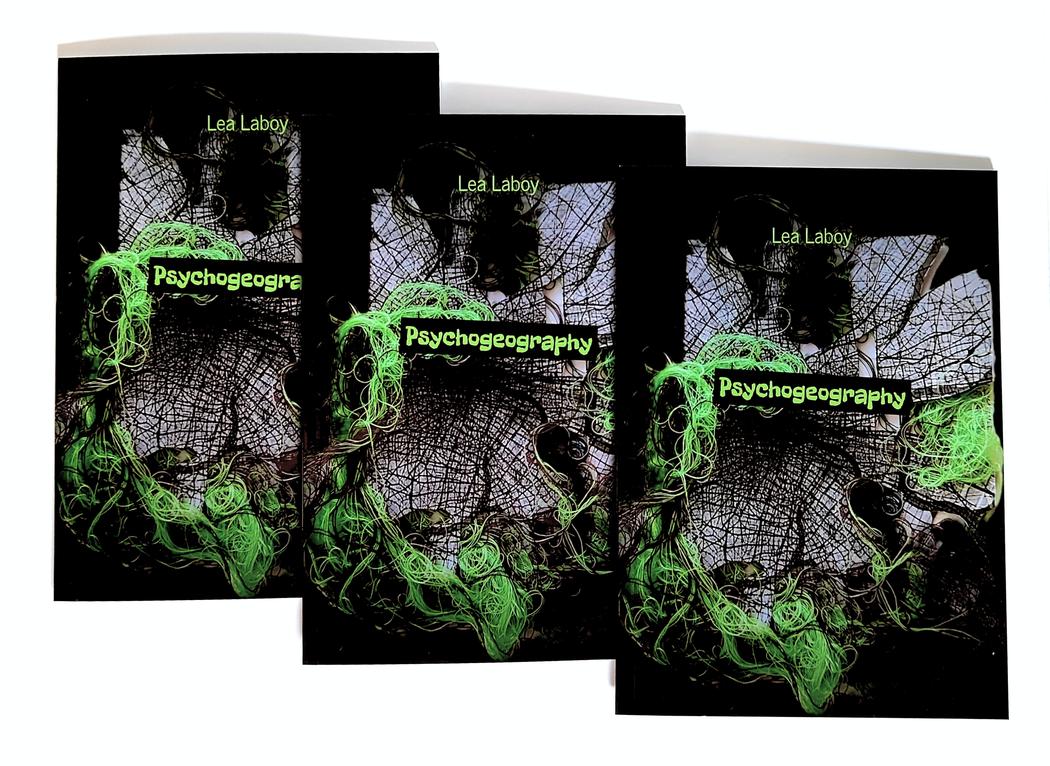

Lea Laboy | Psychogeograhy

Lea Laboy | Psychogeograhy

Many of your works deal with architecture and sacred spaces. What draws you to these environments, and how do you capture their emotional resonance?

This is an obvious topic for me because I’m a believer. I’ve encountered many different religious “environments,” as you call them, and I’ve always wondered what makes this special atmosphere that makes you automatically enter a space dedicated to God and lose yourself in time, while others make you want to leave immediately. When I was studying Art History, professors often attributed this to the idea of telluric lines, giving Chartres Cathedral as an example. However, this theory is unsubstantiated by both historians and archaeologists. Another point of contention was the fact that temples were usually built on the sites of former temples. A good example is the Cathedral of Notre Dame, which was built on the site of the Cathedral of Saint-Etienne, built around the 5th century. The same is true for the mosques on the UNESCO World Heritage List, which I documented in my book. Summarizing, everything science says is probably important, but from my perspective as someone who visited temple after temple every day, keeping records, the most important element is faith, which finds its outlet in prayer. I remember how, after three days on the road, in filth, with no access to drinking water, with temperatures over 40 degrees Celsius (104 degrees Fahrenheit), and with a “minor plane crash,” I finally found myself in a clean room. The only thing I did was get ready and go to the nearest temple. When I arrived, I was truly weak and looked like this. The older men, the temple caretakers, asked me if something had happened or if I needed anything. I told them about my journey. I asked if I could just pray. They nodded, and one of them addressed me with the words: Go and breath the prayer of the ages, it will give you strength. He spoke the truth. When I entered, I was enveloped in an unprecedented peace. This place emanated all the prayers offered here over the centuries. This is the key to my question, because although science studies and documents, without faith it is impossible to properly understand the essence of sacred places.

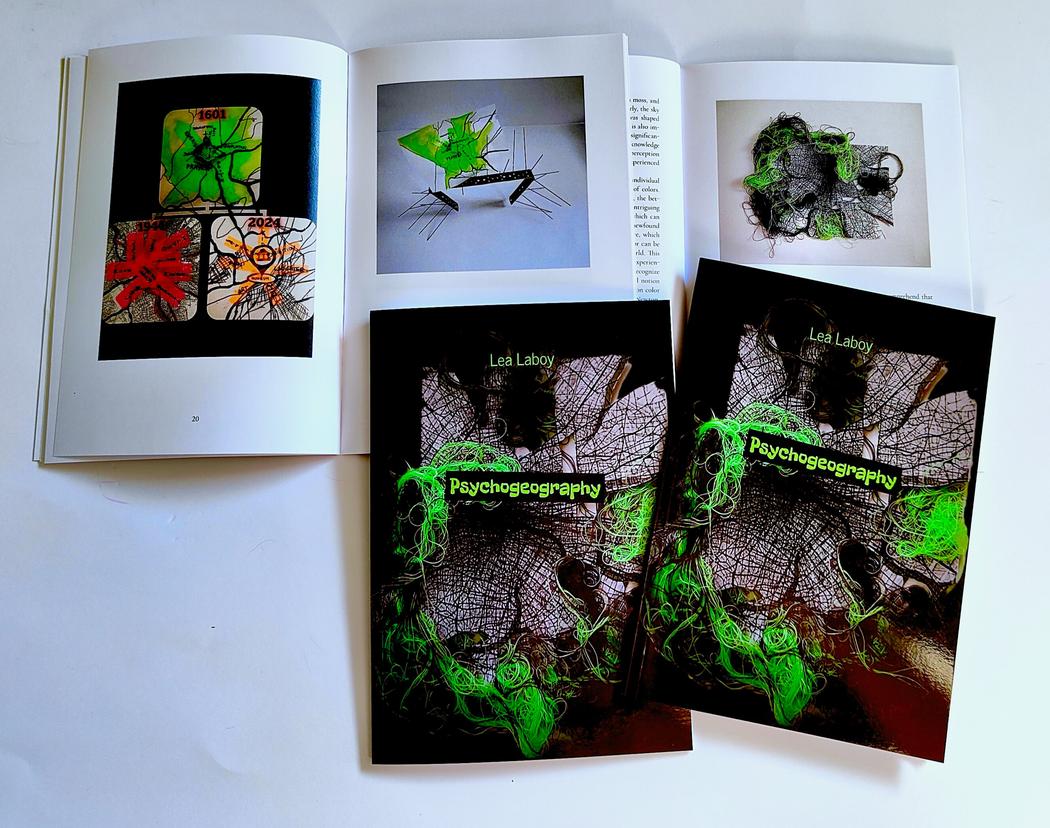

Lea Laboy | Psychogeograhy

Lea Laboy | Psychogeograhy

How do you perceive the act of walking — a key concept in psychogeography — as part of your artistic process?

I see the act of entering psychogeography as a key technique for studying the environment. If we examine this process, we will notice that it has profound meaning because it allows the researcher to establish a personal connection with the surroundings. After all, we live in a world dominated by technology, where personal choices matter less and less. When traveling by public transport, we cannot simply get off at any time and change the route. When we travel on foot, we decide on every element of our journey. We often discover things that are overlooked because they are not on the designated public route, such as secret paths or ruins hidden in groves, and all of this, after all, contributes to the history of a place. When we travel on foot, we also have the opportunity to meet people connected to a given place, which is also an important element in building our image of it.

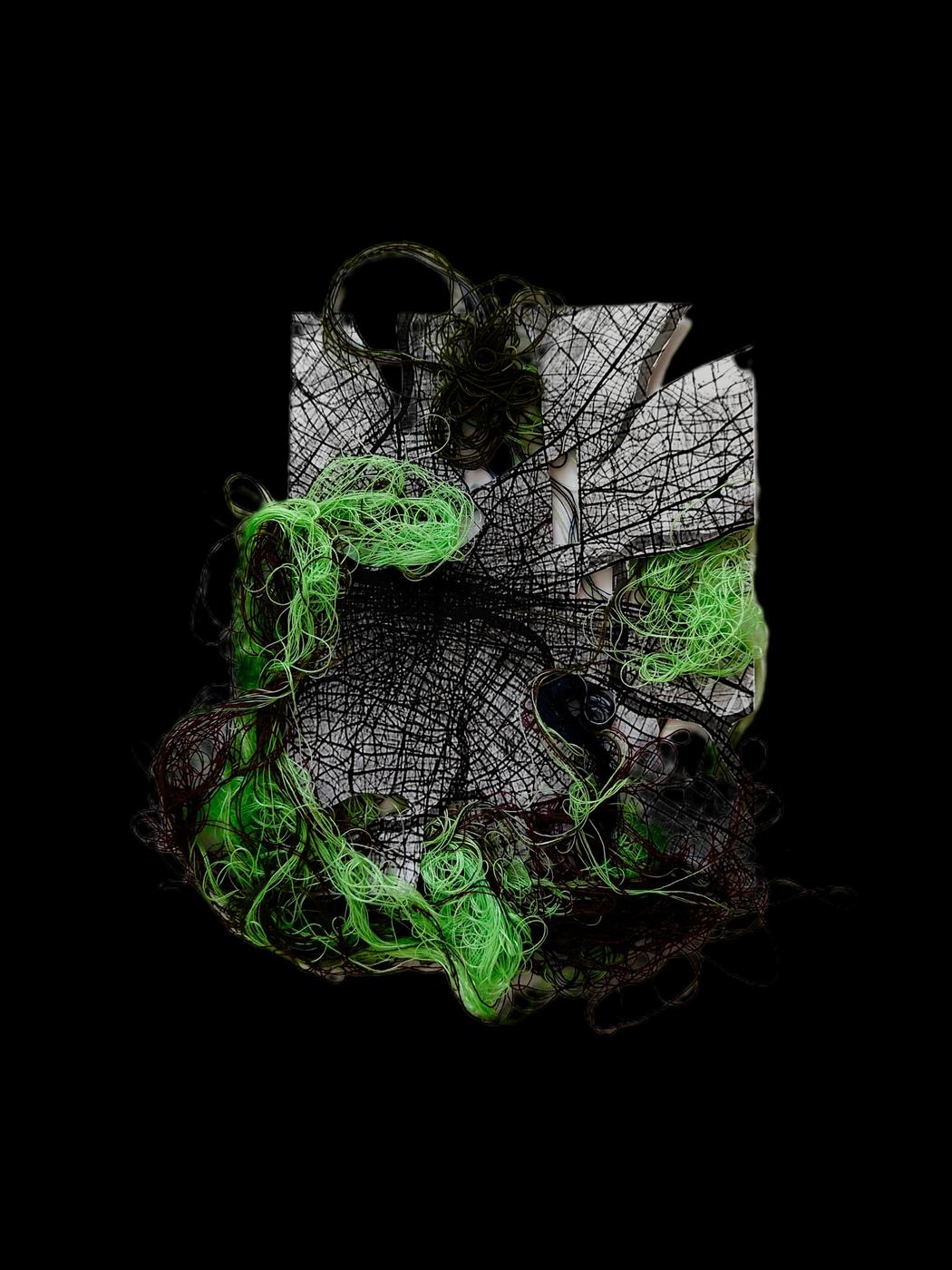

Lea Laboy | Psychogeograhy

Lea Laboy | Psychogeograhy

When working with maps and spatial forms, do you aim to represent a real topography, or an emotional and mental landscape?

When I began my adventure with psychogeography, I focused mainly on actual topography, but over time my thinking began to evolve. I realized that there weren’t really any rules here that I couldn’t adapt or create for my own research needs. In my opinion, psychogeography still remains a very open field, difficult to definitively pigeonhole. Although it was officially named and defined in 1955 by Guy Debord and associated with the activities of the Situationist International, it actually originated much earlier and was widely used by authors such as Edgar Allan Poe, who is considered one of its precursors. Drawing on the work of Edgar Allan Poe, I turned my attention to the mental landscape. One such work is “Erasing History,” which, although it refers to an existing place, overlaps three layers of time. The first refers to the 17th century, the second to the period of World War II, and the third is the year 2024, when I enter the space of this place. This place has evolved throughout its history. First, there was a monastery here, then the harshest prison where the Germans executed innocent people. It was here that a young girl from my family was held captive by German torturers who caught her in a roundup. From this prison, where political prisoners were mainly held, there were only two options: concentration camp or death. The child’s mother undertook a dramatic battle against time, risking her own life. You know, few women would dare to speak out against the German degenerates, knowing their methods, yet she proudly went with her head held high to collect her child, bidding farewell to her family as if she would never return. Today, this place where people were tortured and executed is home to a cultural institution. In the summer, you can hear the laughter of children and the chatter of seniors who enjoy themselves at events here. This work explores the history of the place, focusing on the emotions associated with it today after its deliberate transformation into an entertainment facility, but above all, it questions the humanity of those who made this change and those who would come there to have fun. You can kill a person, distort history, or erase it, but you cannot take away the nature of a place because the stones scream.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.