Mane Yengibaryan

Your background is in architecture and graphic design — how have these disciplines influenced your approach to creating visual art?

Studying architecture trained my eyes to read structure everywhere — even in things that look chaotic. I still instinctively notice grids, proportions, and how elements sit in relation to each other. Graphic design came later and opened a different side of me — the side that plays, edits, cuts, distorts, and questions formats. Architecture gave me discipline and a way of thinking; design gave me permission to experiment and move faster.

When I work now — especially when I turn photographs into patterns — I constantly feel those two worlds overlap: the architectural mindset that searches for logic, and the designer’s curiosity that keeps breaking it to find something new.

In your works, everyday scenes from Armenian life are transformed into vivid patterns and compositions. What draws you to these specific moments and details?

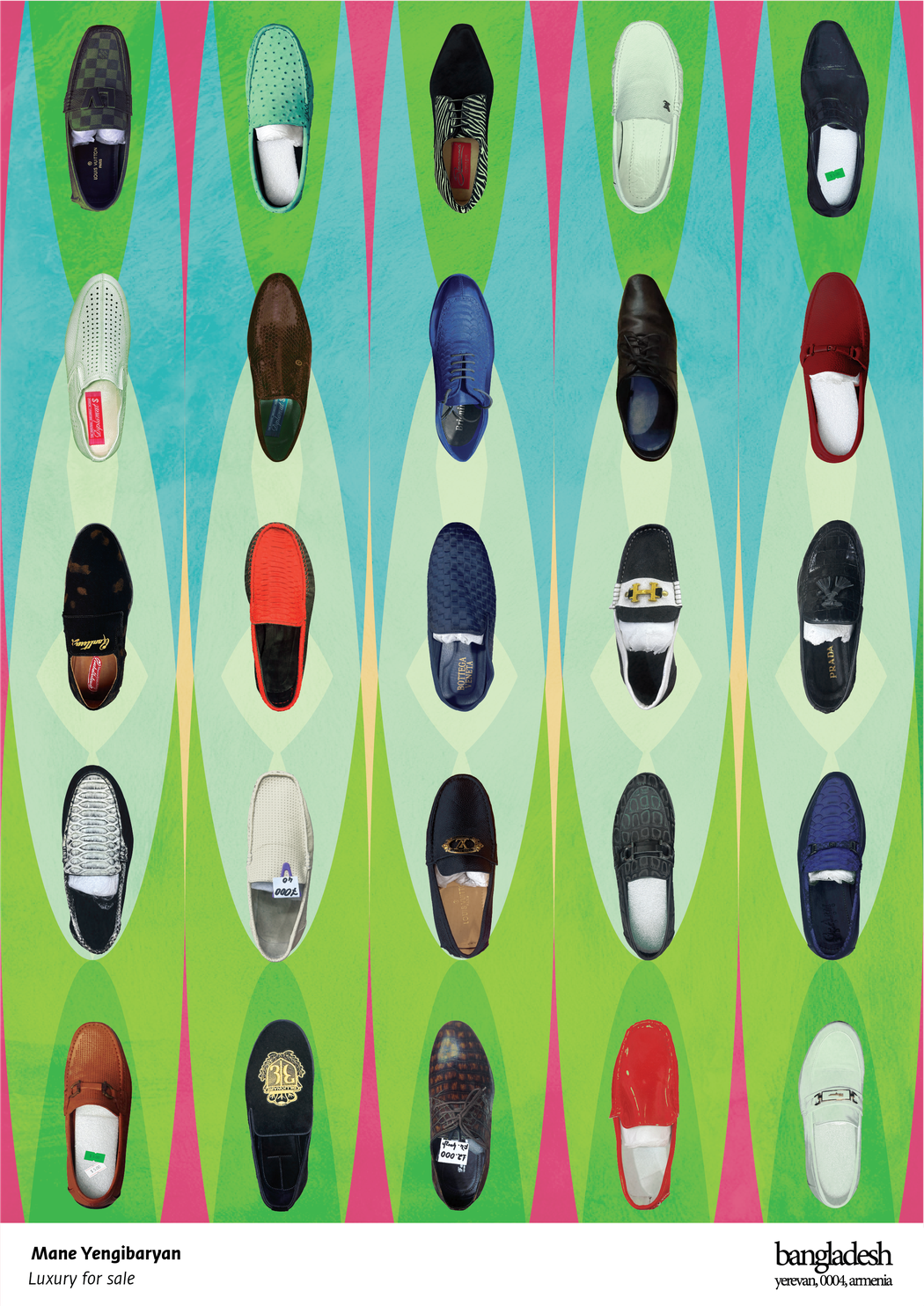

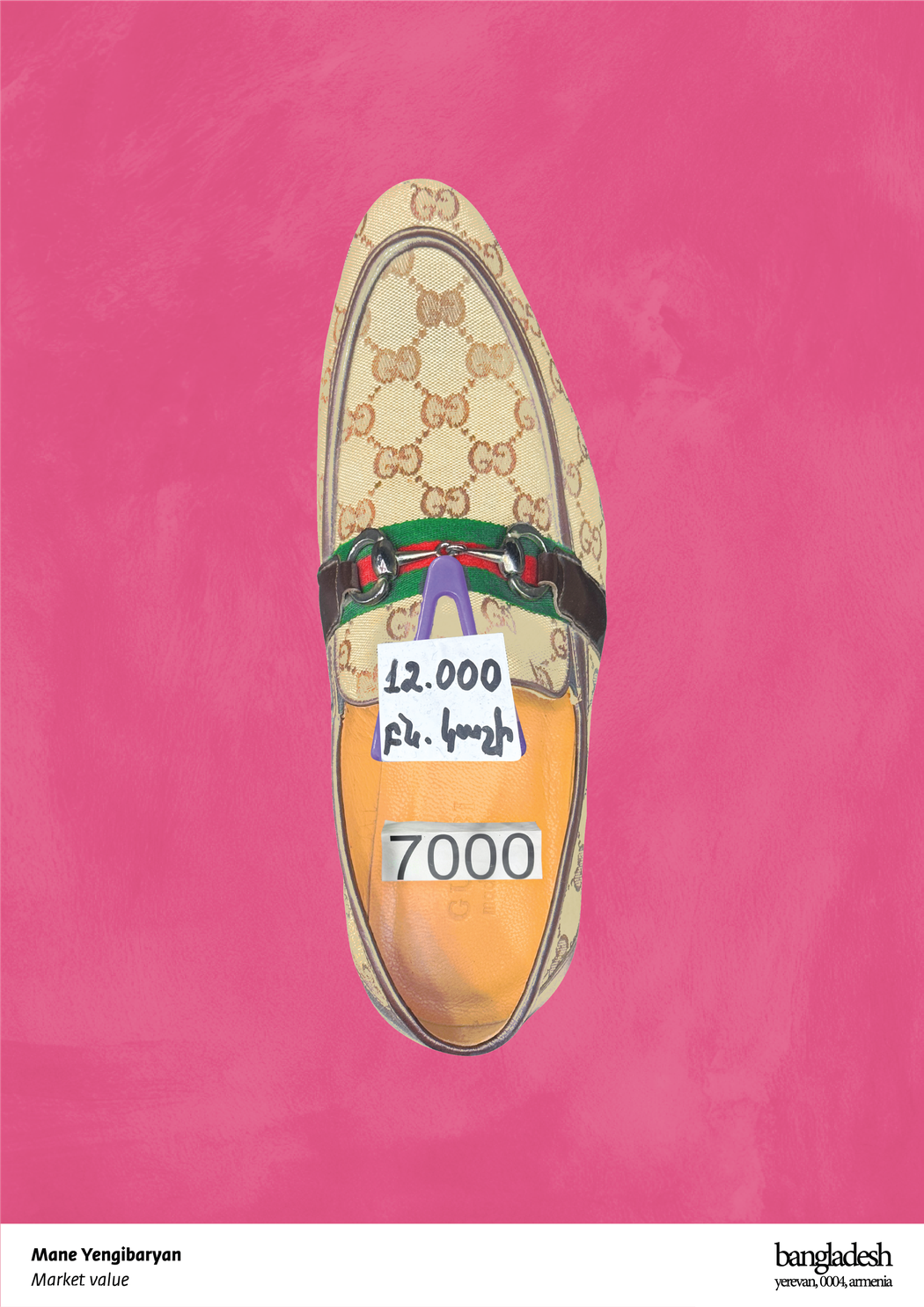

I am drawn to things that are so ordinary that people stop seeing them. Markets, kiosks, improvised displays, objects arranged out of habit — all of that is a visual language that tells a lot about who we are culturally. When I photograph these scenes, I’m not looking for something “beautiful,” I’m looking for what feels honest and uncurated.

Later, when I turn these photos into patterns, I strip the moment from its context and let it live as a pure visual unit. Repetition gives these everyday fragments a new dignity — something that was overlooked becomes central, something informal becomes a formal composition. I think this act of re-framing is what interests me the most: revealing meaning in things that normally pass unnoticed.

Mane Yengibaryan | Bangladesh | 2025

Mane Yengibaryan | Bangladesh | 2025

Many of your images explore the intersection of tradition and modernity. How do you see Armenian visual culture evolving today?

Armenian visual culture today is in a crossover stage. The old codes — craft, textiles, religion, rural gestures — are still very present, but they now coexist with global aesthetics, digital tools, and fast consumption. This creates a visual tension: nothing is purely “traditional” anymore, and nothing is fully “modern” either. You see this mix in typography on the street, in market branding, in how people arrange objects in their homes, even in public space.

What I find important is that a new generation of artists and designers are no longer repeating tradition as a souvenir; they are digesting it, distorting it, translating it into new forms. Armenian culture is shifting from preservation to reinterpretation — and I feel my work is part of that shift.

Could you describe your process of turning photographs into patterns and collages? At what stage does a documentary image become an artwork?

My process always begins with documentary photography — I capture scenes as they are, without staging or aesthetic correction. Later, when I revisit the images, I start dismantling them: I isolate shapes, repeat elements, build grids, or rotate motifs until the original narrative disappears. The transition from photo to artwork happens the moment I stop describing reality and start constructing a new visual logic.

Even though I often remove the context, scale, and spatial information of the original photo, I preserve its emotional energy through color. I exaggerate or refine the colors so that the intensity of the real moment is not lost, only reorganized. The pattern becomes a new system where there is no “main subject” — the thing that was once documentary turns into a rhythmic, vivid structure. This is the point where documentation turns into art.

Mane Yengibaryan | Luxury for sale | 2025

Mane Yengibaryan | Luxury for sale | 2025

Color plays a striking role in your works — intense, sometimes unexpected combinations. How do you choose your color palette?

Color is my way of keeping the emotional temperature of the scene alive, even after the image loses its realism. When I remove context, faces, or spatial cues, something essential could be lost — color is what prevents that. I don’t choose colors to be “pretty”; I choose them to preserve the vibration of the original moment.

Sometimes I amplify what was already there, pushing it to a more synthetic or exaggerated tone. Other times I deliberately introduce unexpected contrasts to emphasize tension, irony, or cultural layering. I see color not as decoration but as an active narrative tool — it replaces what I subtract from the photo and carries the energy forward.

Mane Yengibaryan | Market Value | 2025

Mane Yengibaryan | Market Value | 2025

The series shown here portrays vendors, objects, and street textures with humor and precision. How do you balance critical observation with affection for your subjects?

When I photograph vendors, objects, or street scenes, I try to approach them as both a participant and a witness. I notice quirks, improvisations, and contrasts — the things that might feel amusing, unusual, or chaotic — but I never see them as flaws. There is a human rhythm to these scenes that I deeply respect, and my affection comes from understanding the effort, creativity, and resilience behind these small arrangements of everyday life.

I’m always in touch with the people I photograph. I talk to them, show them the photos, and involve them in the process. Even the presentational photoshoot for this series was done right in the market, and the vendors were helping me — arranging objects, adjusting displays, or just encouraging me. Humor appears naturally because life in the streets is often playful, but it is never at the expense of the people I photograph. By focusing on their inventiveness, energy, and the logic behind their arrangements, I can observe critically while maintaining warmth, trust, and intimacy. In a way, being connected to my subjects is what allows me to see them clearly.

Mane Yengibaryan | The Idle One | 2025

Mane Yengibaryan | The Idle One | 2025

What does “identity” mean to you in the context of contemporary Armenian visual culture?

To me, identity in Armenian visual culture is layered, fluid, and constantly in dialogue with its own past. It is not a single, fixed narrative; it emerges from the intersections of history, daily life, craft, architecture, and personal expression. Contemporary Armenian identity is visible in the way people arrange their homes, how markets organize themselves, the typography on a shop sign, or the gestures and habits that travel across generations.

I see identity as both inherited and invented. Artists, designers, and ordinary people all participate in shaping it — sometimes by preserving traditional forms, sometimes by distorting or recombining them in ways that reflect contemporary life. In my own work, I’m drawn to the fragments that reveal this tension: traces of the past alongside hints of globalization, subtle gestures that feel unique to Armenia yet resonate universally. Identity, for me, is the ongoing conversation between memory, environment, and creativity — a living, visible pulse of culture.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.