Yezi Lou

Year of birth: 1997

Where do you live: Los Angeles, US

Your education: BFA, Illustration, the School of Visual Arts, NYC. MFA, Painting and Drawing, the University of California, Los Angeles.

Describe your art in three words: Playful, uncanny, observant.

Your discipline: Painting, Drawing, Printmaking.

Website | Instagram

Interviewer: Anna Gvozdeva (curator)

Artist: Yezi Lou

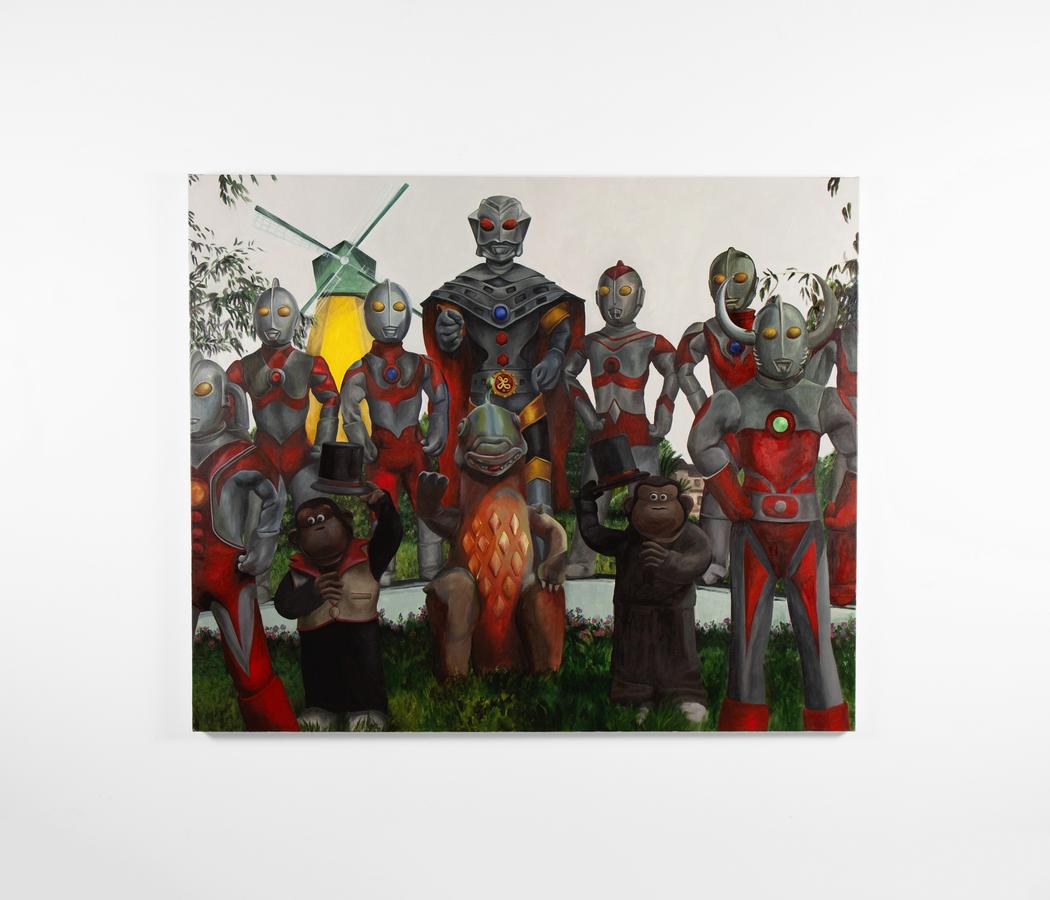

Your paintings often depict mass-produced objects and toys—what draws you to these motifs?

My obsession with objects, particularly consumer goods, is rooted in both cultural context and personal introspection. Wenzhou, my hometown, known for its entrepreneurial culture, was at the heart of a manufacturing boom at the time I was growing up. Many of these products were destined for export, reinforcing the region’s position in global trade. Against this backdrop, my relationship with consumer goods was not only shaped by their material presence but also by the larger forces of commerce, industry, and globalization.

In your work, nostalgia is portrayed not as sentimental, but as political and historical. Can you expand on that idea?

For me, nostalgia isn’t about longing for an idealized past—it’s a form of critical memory. I see it as a political emotion that mediates the tension between collective experience and personal loss. My work doesn’t offer closure; it dwells in the ambiguity of unfulfilled possibilities. The objects I paint often represent moments suspended in time—echoes of futures that never came to be. This layered approach invites the viewer to consider memory as fragmented, unstable, and shaped by broader social transformations.

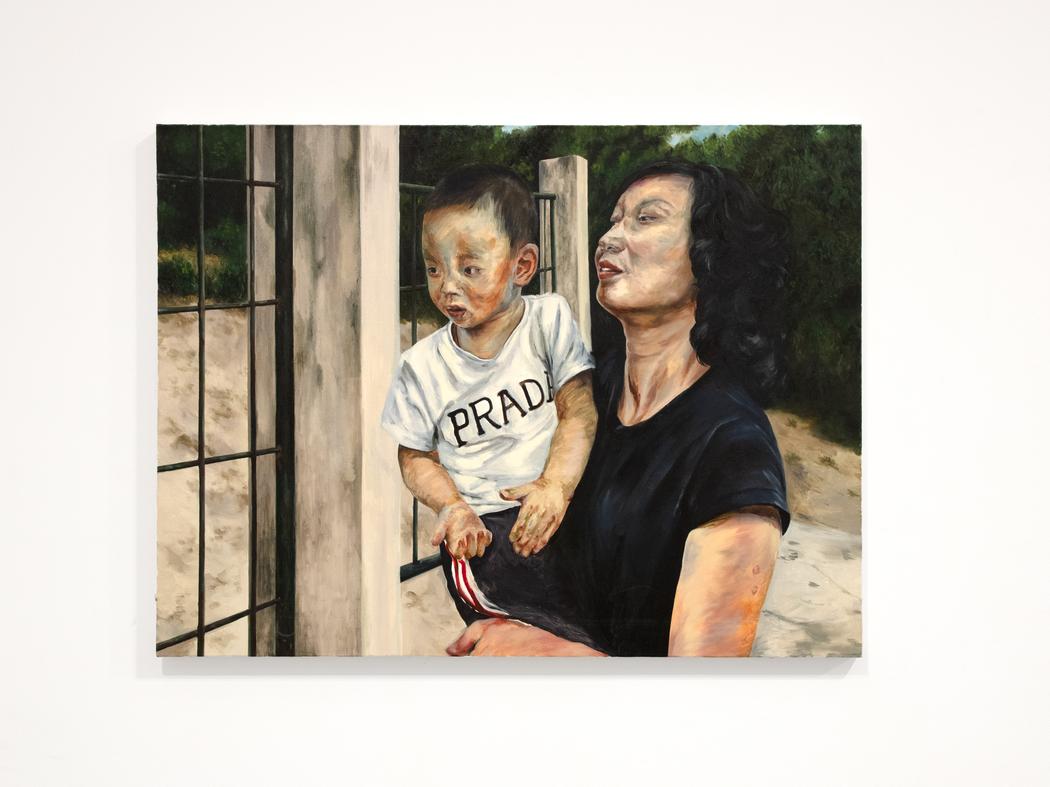

Yezi Lou | One Day In A Zoo

Yezi Lou | One Day In A Zoo

How has your upbringing in Wenzhou influenced the visual language and themes in your paintings?

Wenzhou was a site of explosive entrepreneurial energy—its streets were filled with cheaply produced goods destined for global export. As a child, I was surrounded by these objects, which were both materially insignificant and symbolically loaded. They were tools of social navigation—defining class, relationships, and aspirations. Today, I see domestic space not as a refuge, but as a stage where the pressures of tradition and modernity collide. These contradictions continue to fuel my exploration of alienation, status, and belonging.

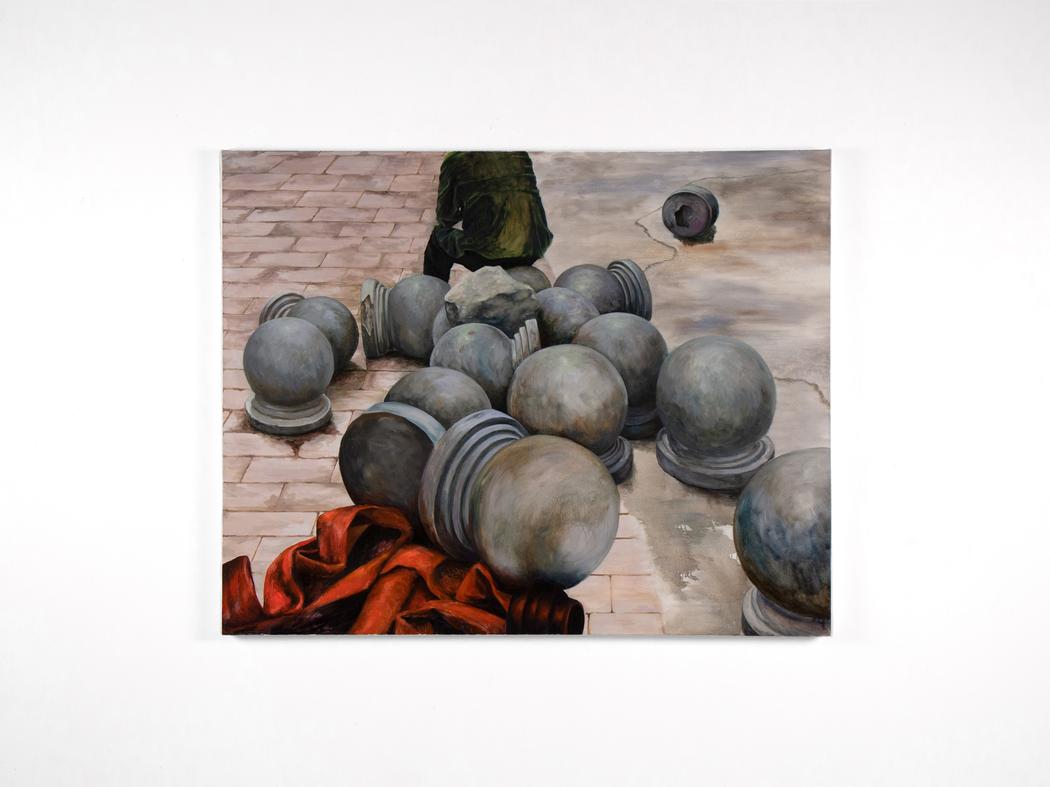

Yezi Lou | Sisyphus

Yezi Lou | Sisyphus

Many of your compositions include broken, discarded, or seemingly cheap objects. What do these symbols mean to you?

I choose objects that were once part of intimate, domestic settings but have since lost their economic value—items often found in secondhand markets or simply discarded. These objects carry a dual weight for me: they are tied to my personal memories growing up in Wenzhou during China’s industrial transformation, and they serve as cultural artifacts of a society reshaped by rapid consumerism. They reflect both the intimacy of lived experience and the impersonality of global commerce, becoming vessels for exploring shifting identities and human connection.

Your portraits often blur or distort identities. What does this ambiguity aim to express?

Blurring faces is a way to protect intimacy while also challenging the viewer’s expectations. It reflects my own discomfort with visibility—particularly as someone negotiating cultural identity and inherited obligations. These distortions create a space where the subject becomes a proxy for emotional states rather than a fixed persona. It opens up a psychological terrain where familiarity is complicated by estrangement, and recognition is deferred or denied.

What role does emotional restraint play in your use of a muted, greyish palette?

Gray is an emotional buffer—it allows me to express vulnerability without direct exposure. It embodies ambiguity, detachment, and introspection. While brighter colors might assert or define, gray suspends meaning. It holds emotional weight while remaining elusive. My use of gray also reflects a desire to delay immediate emotional response and encourage a longer, quieter contemplation.

Yezi Lou | We Reached A Consensus

Yezi Lou | We Reached A Consensus

Are there particular memories or stories from your childhood that regularly resurface in your creative process?

Yes—one that continues to appear on my work is the brief time we had a Dalmatian when I was very young. We didn’t keep her for long, but her presence has lingered with me. The image of the Dalmatian recurs subtly in my paintings, not just as a visual motif but as an emotional undercurrent. It’s a melancholic and layered memory—tied to questions of family, folklore, gender roles, and social class. Over time, that early memory has evolved into a symbol of both confinement and the new understanding for freedom.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.